Tuesday, August 10 2021

What springs to mind when you hear the word “art”? Maritime art isn’t limited to the beautiful paintings you see hanging in art galleries, but encompasses a diverse range of arts and crafts, from travel posters to figureheads. Figurehead carving may have been around since Ancient Greece, but has it become a lost art?

What are figureheads?

Figureheads are essentially a carved representation of the spirit of the ship. This can be in the form of people, beasts or mythological creatures. They were primarily built of wood and attached to the bow of the vessel.

Ship figureheads © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

It all began thousands of years ago, as far as Ancient Greece and beyond…

Although the precise dates are unknown, figureheads were reportedly used by the great civilisations of antiquity. The purpose of these wooden carvings varied across cultures- while the original purpose of Ancient Greek figureheads was to symbolise acute vision and ferocity, Vikings used figureheads to protect their vessels from evil spirits. Egyptian and Phoenician seafarers also adopted this tradition, placing replicas of holy birds and horses on the bow, with the intended purpose of providing absolute protection for the vessel and her crew. By the Baroque era you start to see more elaborately designed carvings on high ranking ships, similar to the examples featured in this blog.

People believed that these icons had strong magical and religious significance. Sailors were notoriously superstitious men and viewed the figurehead almost as if it were a living being. They also believed that a ship needed to find its own way and could only do so if it had eyes (in the absence of a figurehead, many cultures painted eyes on the ship’s bow and many still do). The superstition went so far that, if the figurehead was damaged in any way, it was taken as a sign of bad things to come!

Figurehead from HMS Orpheus 1857, New Zealand Maritime Museum.

Have you ever wondered why the most popular figureheads were women? Once again, sailor superstitions are to blame. Sailors considered the presence of female figureheads as representing an offering to the oceans. They thought the figurine of a topless lady would entice the ocean Gods and spirits to its beauty, calm the seas, and allow the vessel to proceed on course without causing any harm. If you want to learn more about why a ship is female, you can read more here.

In Northern Europe, dragons, dolphins, serpents and other mythical figures were more common. Swans, for example, symbolised grace and nobility and lions were the favourite figurehead on war ships as they represented bravery, victory and glory- a very necessary attribute for war!

Lion figurehead in St Petersburg, Russia © Denis Ivanov.

Who made figureheads?

For a span of 200 years, the figurehead carving industry was booming, with dockyards across Europe and America employing Carvers to create ship ornamentation. Ship carving in Britain was a highly specialised profession taught through a seven year apprenticeship scheme. Meanwhile, Carvers in mainland Europe were trained in fine art and enjoyed an elevated status. Swedish sculptor Johan Tobias Sergel for example, designed and made wax maquettes (preliminary scale models) for figureheads.

Lithograph of Johan Tobias Sergel (1740-1814) by Alexander Clemens Wetterling

British figurehead Carvers, on the other hand, received far less notoriety than their European counterparts. Furthermore, the profession of Carver in Britain was rarely documented as a specific role, since Carvers often took on additional employment during quieter periods such as carrying out gilding work on ships or even carving garden sculptures.

How were figureheads made?

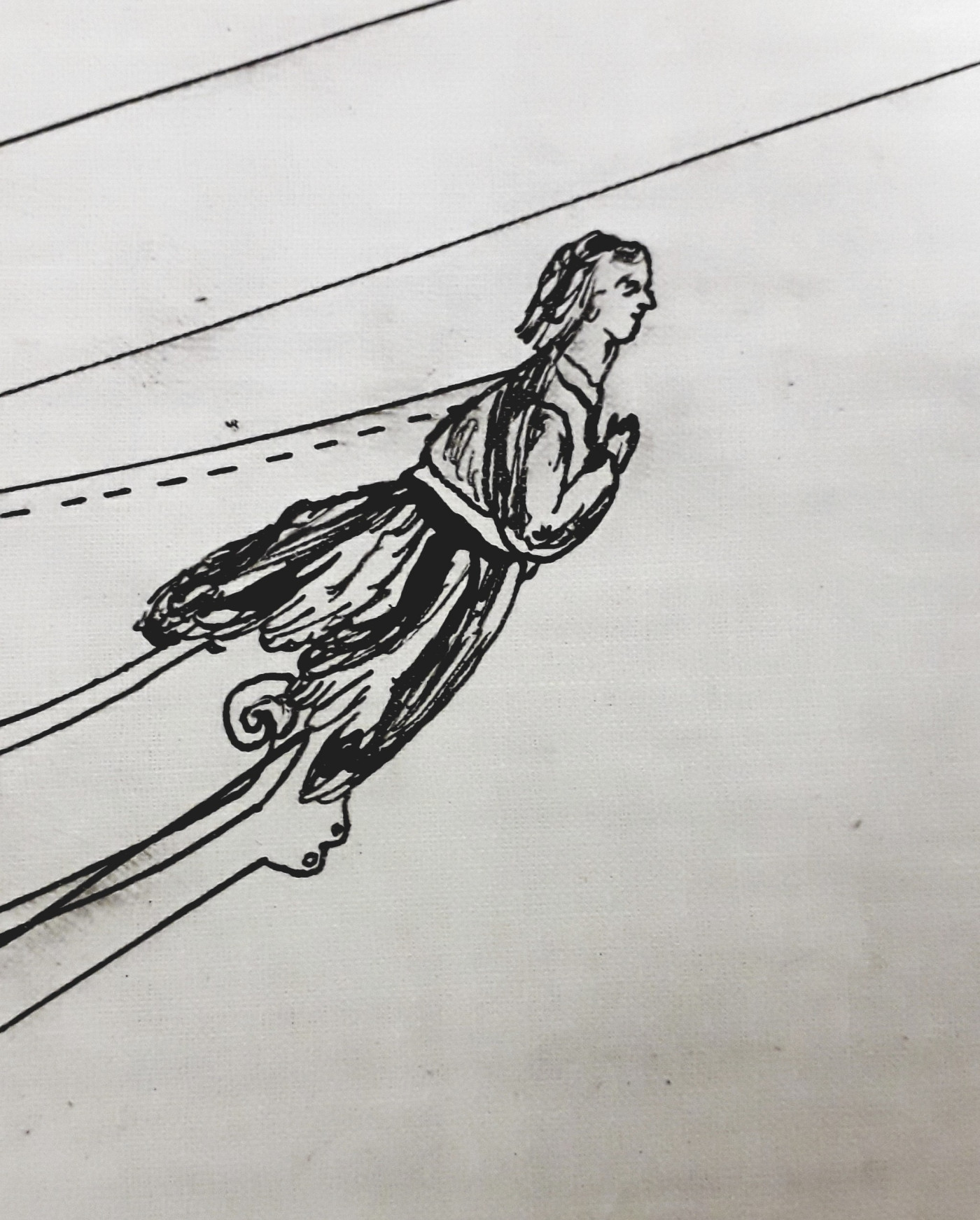

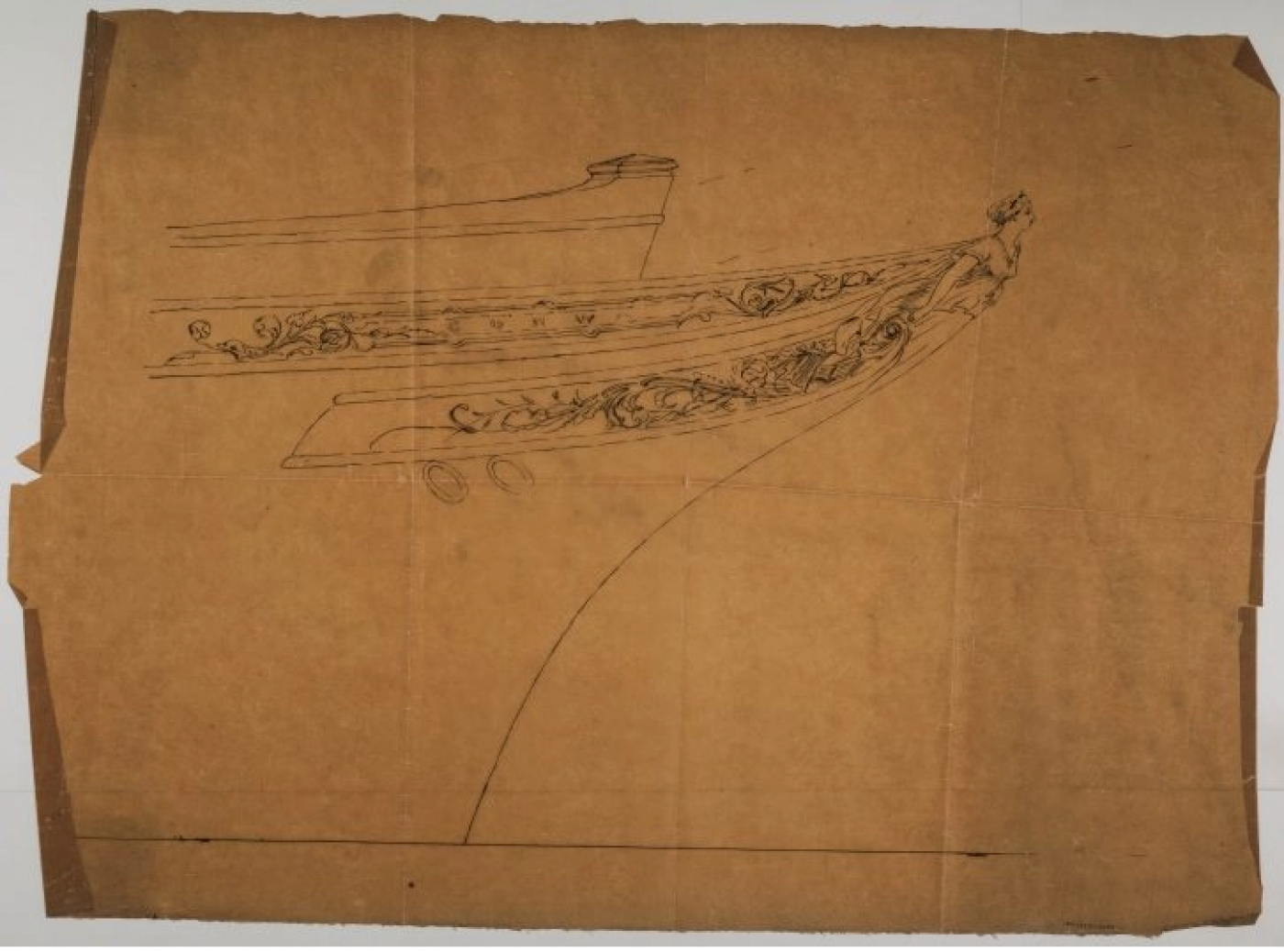

The first stage in the figurehead making process was creating a sketch or maquette for reference. Our own archive holds numerous examples of figurehead sketches:

This figurehead sketch was made for Sherwood (1883) built in Whitehaven.

This intricate drawing was created for the figurehead on Loch Maree

Another important preliminary step was to select the wood type, which would depend on multiple factors including availability, transport costs, and regulations set by the Navy. Elm, oak, mahogany and teak were typically chosen for figureheads due to their durability. However, in the 1700s, the Navy Board stipulated that pine be used in lieu of these heavier materials and, eventually, figureheads were almost exclusively made of pine. Once the materials and sketches had been prepared, the carving process, using a gouge and mallet, could begin.

When the Carver was satisfied with the figurehead’s shape, they would paint it, which simultaneously decorated and protected the wood. Initially, figureheads were painted all in one colour, with white and yellow being the most popular choices. The frigate Guadeloupe, launched in 1763, is believed to be the first ship to have a figurehead painted in multiple colours. The 1825 edition of The Gentleman’s Magazine includes a description of Guadeloupe’s colouring: “The Guadeloupe Frigate...was the first that had a painted side, and the figure head of various colours. We called her the Nancy Dawson. Turpentine sides and yellow heads were the general costume.” Subsequently, painting figureheads with a variety of colours became the norm. The Deptford Yard letter book lists the variety of colours and materials available for paint in the eighteenth century: ‘white lead, linseed oil, rapeseed oil, hempseed oil, Spanish whiting, chalk, gold colour, Venetian red, lamp black, Spanish brown, and port red’

The figurehead of Cutty Sark.

When it comes to famous figureheads, there is no better place to start than Cutty Sark!

‘Nannie’ figurehead © Paul Brown/Rex Features

Nannie the witch is probably one of the most recognisable elements of the Cutty Sark, with her outstretched arms as if she is giving directions to the generations upon generations of sailors on the vessel.

The name Nannie came from Tam O'Shanter, a poem by Robert Burns, which coincidentally was also the inspiration for the name of the ship itself, Cutty Sark.The poem tells the story of Tam the farmer, who encounters a group of witches in Alloway Kirk, including a witch named Nannie. Nannie was dressed only in a ‘cutty sark’ (a Scottish name for a short nightdress). In the poem, the witches chase Tam after he calls out to them during a dance. He makes his escape on his horse Meg but just as he reaches safety, Nannie grabs the tail of his horse and pulls it clean off- this is why Cutty Sark’s figurehead is holding a horse's tail!

Through Cutty Sark’s long career, she has had numerous reproductions of Nannie installed. The figurehead positioned on the bow of the vessel today is a much newer commission as the original figurehead, created by the legendary ship’s Carver Frederick Hellyer, was damaged in a storm in the late 19th century. A new figurehead was installed in 1957, but this figurehead has now also suffered due to environmental damage and rot. Last year a new figurehead was commissioned, aiming to reflect the beauty of the original ship design and celebrate the art of ship carving.

This video from the National Maritime Museum shows the construction process of Nannie by Andy Peters, one of the only ship figurehead Carvers working in Britain today:

You can view our archival documents relating to Cutty Sark here.

The figurehead of Jane Slade.

Another figurehead, that is perhaps less well known, is the figurehead of Jane Slade. Around 1929, the ship Jane Slade was found stranded in a creek near Fowey by the young Daphne du Maurier, who was staying at her family’s holiday home nearby. The creek Pont Pill, where Daphne found the ship, was regularly used to moor ships that were laid up and no longer in use. Daphne was immediately taken by the beautiful appearance of the ship’s figurehead, whose name and likeness had been inspired by the original shipowner’s wife. Jane Slade, classed by Lloyd’s Register and built by William Salt Slade in Polruan, had operated as a schooner in the fruit trade before being abandoned.

Replica of Jane Slade's figurehead © Joanna Wing.

Inspired by the figurehead, Daphne sourced Slade family letters and paperwork relating to the Polruan boatyard where Jane Slade was built. This led to Daphne writing her first novel The Loving Spirit, which tells the story of a Cornish shipbuilding family including a character called Janet Coombe, who was based on Jane Slade. When the schooner was eventually broken up, the Slade family gifted the Jane Slade figurehead to Daphne. It remains inside the du Marier family’s holiday home to this day, with a more weather-hardy replica on display outside.

Is figurehead carving a lost art?

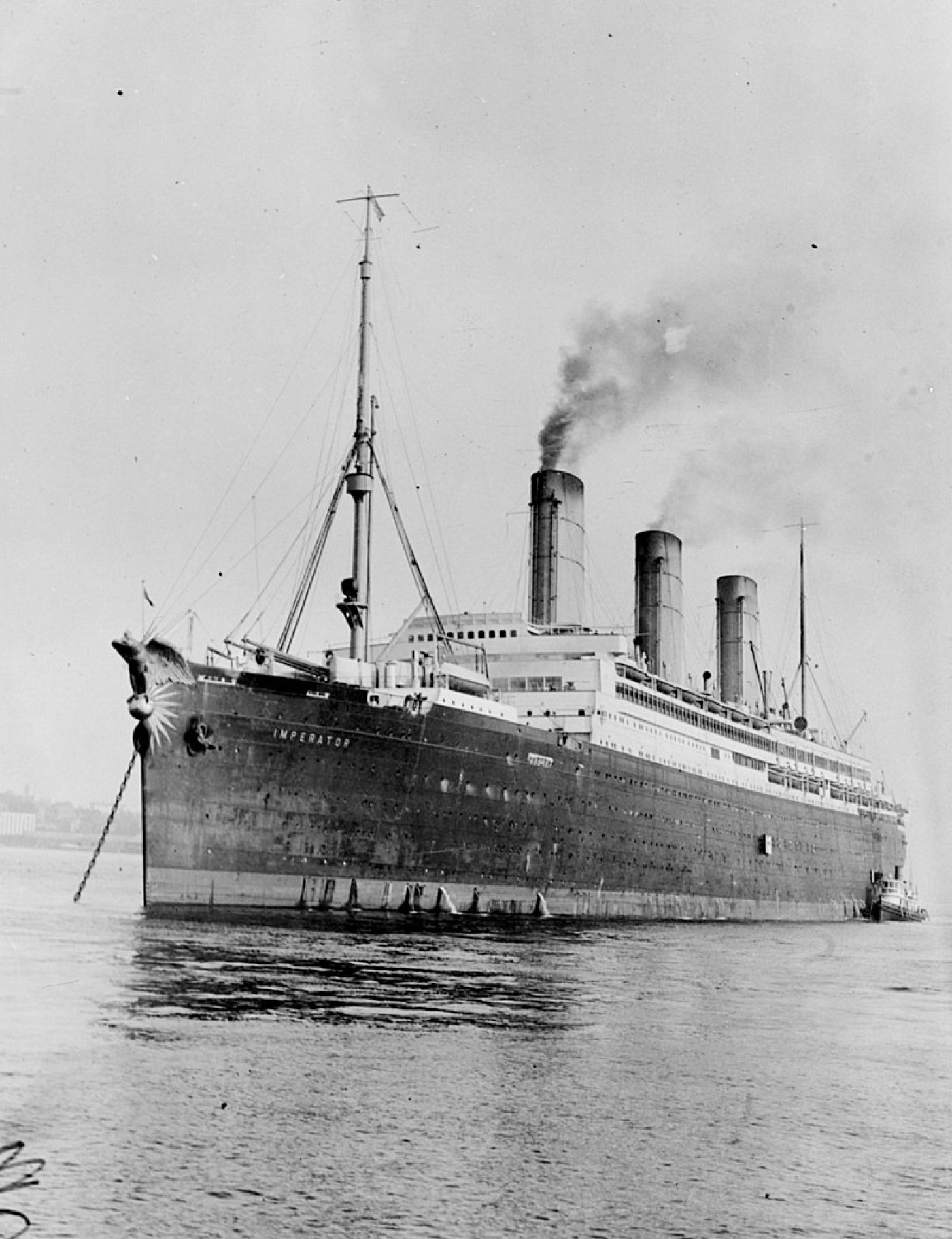

Despite their elusive nature in historic records, we do know that there are far fewer figurehead Carvers than there once were. The number of known Carvers in the UK has decreased from around 290 in the 1800s to three today. The steep decline in demand for carved ship ornamentation can be attributed to the development of the metal hull, firstly with iron and then steel hulled ships, which brought about changes to hull shapes. A short-lived revival came with the development of the composite sailing ship from the mid-19th century and many of these magnificent ships had a figurehead, but the revival did not last. There was one notable exception- the German passenger liner Imperator displayed a magnificent bronze eagle as her figurehead, adding length to the ship to ensure she was longer than Cunard’s Aquitania!

Imperator at anchor, circa 1913.

However, the heyday of the figurehead was over, but thanks to the few remaining specialists today, figurehead carving is not a lost art form.

References

A. J. van der Horst, 2001, Painting and preserving the ship in the 17th and 18th centuries, The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, Wiley Online Library [accessed 19th July 2021].

Ann Willmore, The Loving Spirit, Daphne du Maurier's first novel, celebrates its 90th anniversary in 2021, (dumaurier.org) [accessed 19th July 2021].

David Pulvertaft, 2014, Ship Decoration 1630–1780, The Mariner’s Mirror, Volume 100, (tandfonline.com)[accessed 16th July 2021].

Erica McCarthy, 2015, Ship Carvers in eighteenth-and nineteenth-century Britain, The Sculpture Journal [accessed 16th July 2021].

Peter Willis, The Figurehead Carver, Chelsea Magazine Company, (classicboat.co.uk) [accessed 15th July 2021].

Royal Museums Greenwich, Ship figureheads and decoration, National Maritime Museum (rmg.co.uk) [accessed 15th July 2021].

Royal Museums Greenwich, The Art Of Ship's Figurehead Carving, Royal Museums Greenwich (youtube.com) [accessed 15th July 2021].

The Jane Slade Project (fowey.co.uk) [accessed 19th July 2021].