Tuesday, April 03 2018

1837 proved to be an integral year both for British and maritime history. Not only did Queen Victoria succeed her uncle William IV to the throne on the 20 June but two important ships called Sirius were built, signalling progress in the maritime world.

A First for Lloyd's Register

The first iron vessel to be classed by LR, the Sirius, was launched in 1837. She was constructed at William Fairbairn's yard in Millwall for use on the River Rhone. Classed by LR, she appeared in the Register Book in 1838 with the class 'A1'. However, as iron was seen as experimental in ship construction, a term of years was not added to the classification and she was subject to annual examinations.

Following the industrial revolution, shipbuilders were finding new materials, technologies and methods in which to build ships, moving away from wood and sail. The society were cautious when it came to classing new types of ships or technologies, preferring to describe them as 'experimental' and ensuring that they were checked regularly. This was largely due to these technologies being unknown, with little or no experience of how they sail, how safe they are or how long they last. Once proper knowledge and experience had been gathered of new materials or technology, then the society would issue definitive classification rules. With iron, for example, the General Committee were happy to give any ship an 'A1' classification, if it 'was reported to be of good and substantial materials and with good workmanship' but readily admitted that they knew little about iron itself so could not give it a term of years. In 1855, the new Rules for Iron Ships was published with LR recognising that the technology was still developing so the rules would have to adapt.

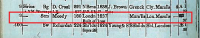

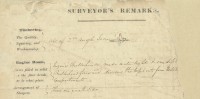

If you look closely at the scanned reports below you can see the sketches of the surveyor George Bayley which he drew to highlight new and interesting ship-building techniques including the rivets!

A Race Across the Ocean

Remarkably in the same year another ship called Sirius was built by Robert Menzies & Son in Leith for the London-Cork route that was operated by the Saint George Steam Packet Co. A side-wheel wooden-hulled steamship, she measured 178 feet 4 inches long, 18 feet 3 inches depth of hold with a gross registered tonnage of 703; she had a two-cylinder steam engine that drove two paddlewheels producing a maximum speed of 12 knots.

Around the same time that the Sirius was being built, the British and American Steam Navigation Company (BASNC) was building its first transatlantic steamship, British Queen, and the Great Western Steamship Co. was building their Great Western. Unfortunately for BASNC the firm that had been hired to build the British Queen collapsed, putting her building on hold until Robert Napier was hired. This meant that Great Western edged closer to being completed first and making the first steam powered transatlantic voyage. Laird suggested to Smith that they charter the Sirius in order to beat Great Western. Sirius left Cork on 4 April 1838, four days before the Great Western departed Avonmouth. The Great Western came within one day of overtaking Sirius. During the voyage, coal ran low. It is alleged that the crew used newspaper, furniture and a spare mast as a fuel supplement during the voyage. This is famously replicated in Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days. Sirius completed the voyage in 18 days, 4 hours and 22 minutes and beat the Great Western. It was established however that Sirius was too small to undertake transatlantic voyages and she was returned to her owners. Because BASNC did not establish regular transatlantic crossings immediately and would close as a company in 1841, Great Western has taken its place in history as being the first transatlantic voyages made by a steam ship. In 1847, the Sirius was wrecked after hitting rocks in the dense fog of Ballycotton Bay, Ireland. Most of the passengers and crew were rescued though 20 lives in total were lost.

A Forgotten Maritime Hero

Junius Smith has largely been forgotten to history, with most remembering the great 19th century engineers like Robert Napier and Isambard Kingdom Brunel. However, Smith is considered to be the “grandfather of the Atlantic liner”. Smith, born in Plymouth Connecticut in 1780, initially trained as a lawyer but subsequently moved to London in 1805 to become a merchant. On a trip to New York, the sailing packet Smith was on became stuck for 54 days. This experience both frustrated and inspired Smith who wrote, in an article published in the American Rail Road Journal (1832), that transatlantic steamships should be built to make crossings from London to New York quicker, easier and safer. His plan was to build four ships that would carry out the voyages on a rotation. Scottish shipbuilder Macgregor Laird took on board Smith’s idea and invested in the construction of these ships. Smith established the British and American Steam Navigation Company (BASNC) in 1839. Despite Laird’s investments, Smith still had to fight for his ideas, with many of his peers sceptical about the lasting power of steam engines and their safety, preferring the romanticised age of sail. In letters to New York journalists, Junius Smith argued in fervent favour of the power of steam and the impracticalities of sailing ships. He notes that “whatever nation, England, France or America– and I think that it will be one of the three– has the largest and greatest number of steam ships of war, will command the ocean.”[1]

Despite a lack of belief in Smith’s work, the BASNC had three steam ships in its fleet; the British Queen, Sirius and President. Unfortunately the BASNC had limited success. In 1841, the President set sail from New York but was lost when she encountered severe gales causing the closure of the BASNC. The closure led to Smith returning to America. In 1851 Smith was outspoken in the support of the abolition of the slave trade which led to him being beaten by ‘patrollers’. He was admitted into the Bloomingdale Asylum where he subsequently died in 1853.

- [1] J. Smith, “Letters on Steam Navigation-19 October 1838”, in B. Silliman ed. American Journal of Science (New Haven, 1838), 333