Friday, January 19 2024

With new manufacturing methods and stringent testing in place, in just three years from 1880-1883 the volume of steel used in shipbuilding increased by almost five times to 166,000 tons. [1] Demand for steel, in particular rolled steel has increased steadily ever since. Ensuring the consistent quality of the steel produced is paramount.

In their blog ‘Lords of the Seas: Shipbuilding Steel’ (2020), Metinvest Group, a notable vendor of materials to the Ukrainian and global shipbuilding markets, explain that: “A vessel hull is always in contact with water (both fresh river and saline sea water) and is exposed to other impacts, for example, on a pier while mooring at a seaport. Therefore, the hull material must ensure the set level of strength, flexibility and viscoelasticity under different thermal conditions. Rolled steel used to manufacture vessel and ship hulls must be sufficiently resistant to corrosion, but at the same time be easily deformed (bending and cutting) and welded at dockyards.” [2]

Steel quickly found favour over iron as a shipbuilding material because it is stronger and ultimately was cheaper. The classification society Lloyd’s Register first approved a steel ship in 1866, the screw steamer Annie, launched by Samuelson of Hull in 1864, classed ‘A1’ but still cautiously marked ‘Experimental’ in the Register Book for 1867. She was riveted, rather than welded which came to the fore during the First World War. In 1866 a team of four Lloyd’s Register surveyors had been invited to visit the works of the Barrow Haematite Steel Company in north-west England. They approved the quality of the steel being made and reported favourably on the construction of a 1,500 ton vessel, permitting scantlings of a thickness 25 per cent less than those for an iron ship.

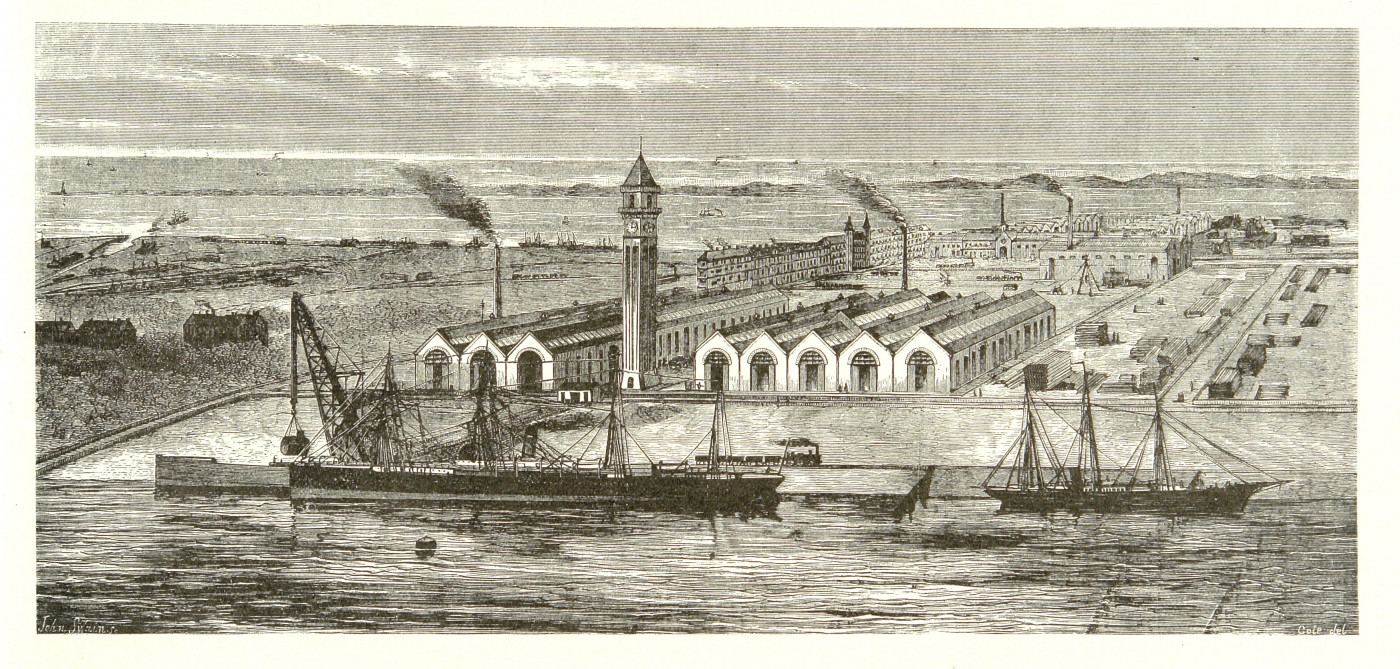

Barrow Haematite Steel Company's works by David Knight.

The Barrow Ship Building Company's iron shipbuilding yard in the latter part of the 19th century.

As with iron, the Society found that the quality of production varied enormously from one works to another. Over the years the expertise of Lloyd’s Register surveyors in inspection would be widely and rigorously tested to ensure ships, their machinery and boilers were made from steel of an appropriate quality. Consistency came only with alternative methods of production. The Society’s surveyors gave good reports of the steel produced by the Bessemer process. In 1879 the Visitation Committee noted in its report on Newcastle, ‘Steel giving great satisfaction. Works better and more suitable for shipbuilding than iron’. In the same year the Society classed the Rotomahana, built in Dumbarton by Wm Denny & Bros for the Union Steam Ship Company of New Zealand, the first large, ocean-going steel-built steamship.

Rolled steel for shipbuilding needs a specific set of characteristics – it needs to be resistant to corrosion and to the strains of working in harsh marine environments - strength and resistance are key. All of these elements needed to be considered in the smelting processes, and as manufacturing techniques evolved from riveting to welding. As the demand to use steel grew, Lloyd’s Register insisted on the most stringent testing, eventually appointing Inspectors of Forgings in 1882. Steel also began to be used for parts of the vessel such as the engine and boilers, and the stern and rudder frames. From 1884 the Lloyd’s Register ‘LR’ steel testing stamp was used - the brand that surveyors stamped into steel as proof of approval.

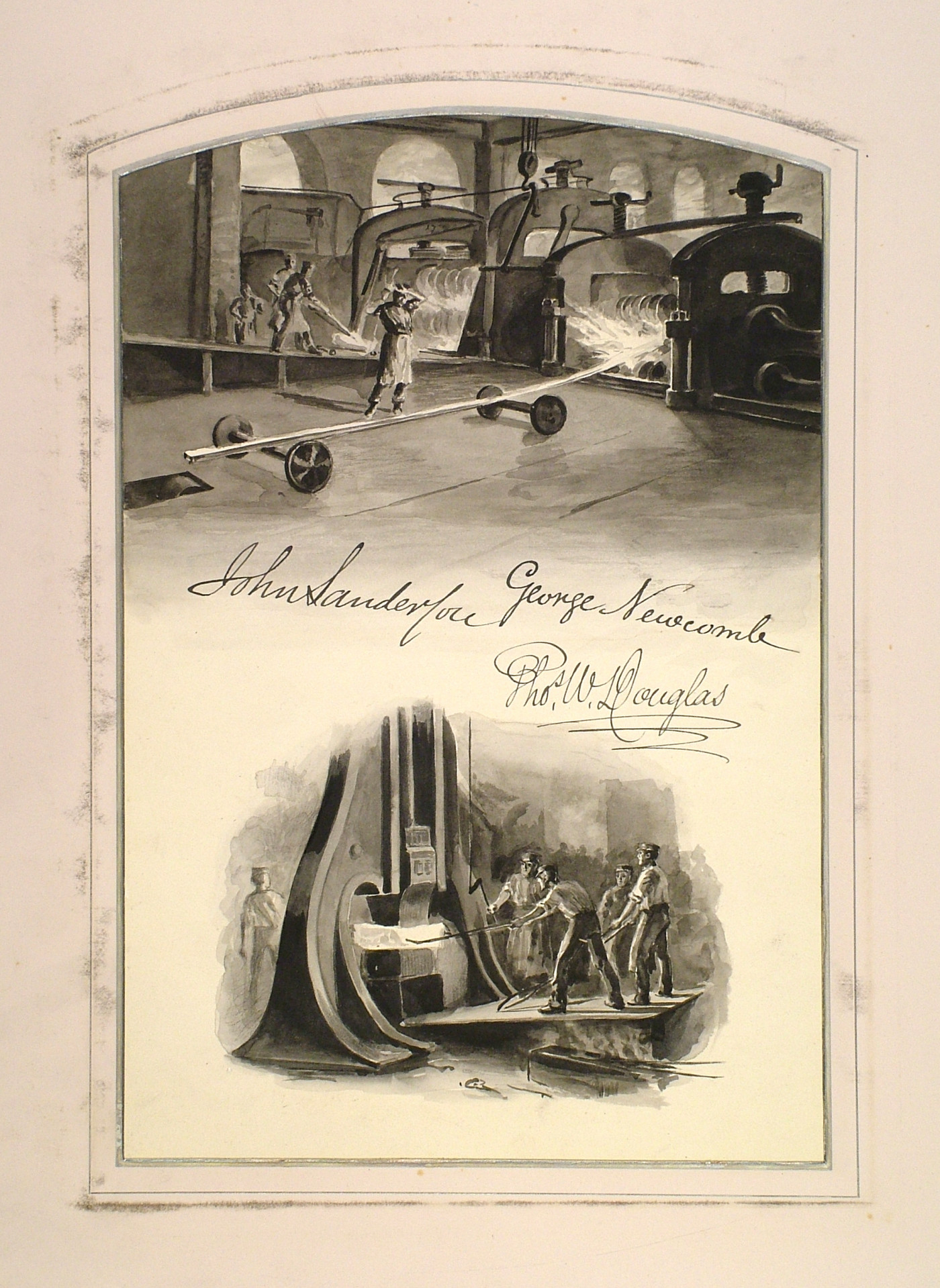

A 19th century steel rolling mill and drop forge hammer drawn by Harry Cornish in 1884.

But for Lloyd’s Register’s Chief Surveyor, Benjamin Martell, Bessemer steel was still not good enough. Instead, in a paper to the Institution of Naval Architects in 1886, he advocated the Siemens–Martin or open-hearth process and it was partly thanks to his influence that the latter became the accepted method of producing steel for shipbuilding. The volume of steel used rose rapidly once the efficacy of the new process had been proven, increasing from 35,000 tons in 1880 to 166,000 tons in 1883. By 1914 steel vessels made up more than 21 million tons of a total of nearly 23 million tons classed by the Society; iron ships accounted for just 1.4 million tons and wooden ships a mere 17,000 tons.

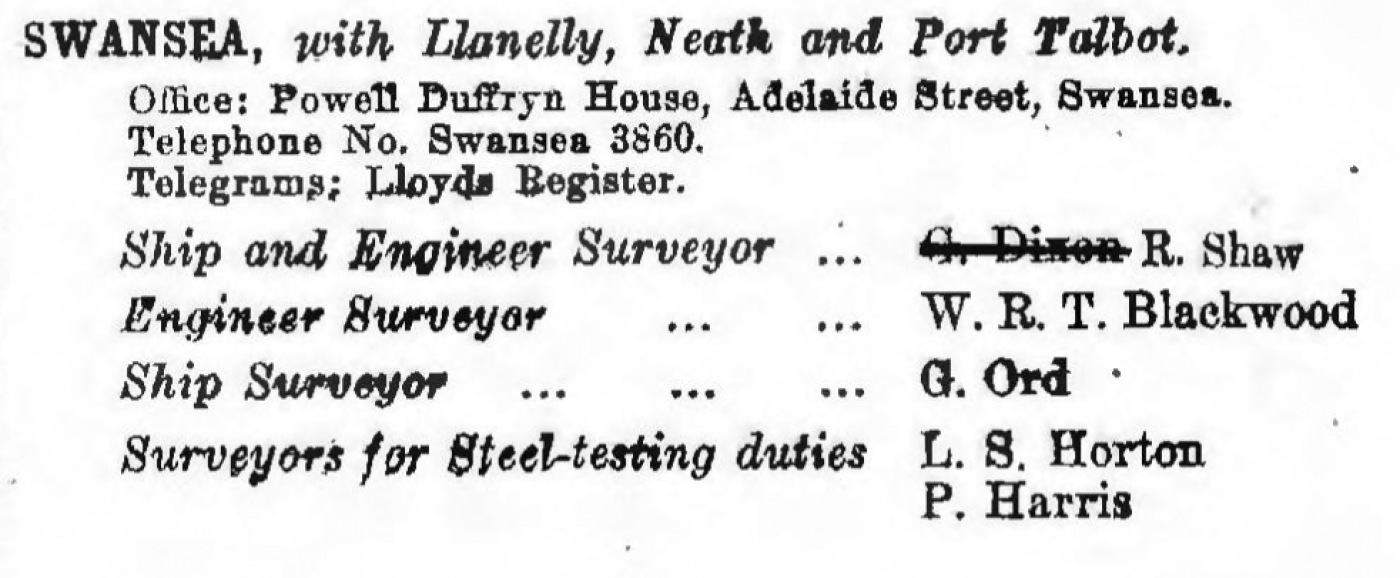

Today, plants that manufacture heavy plates for the shipbuilding industry smelt special steel grades and continue to work to the specifications of national and international classification societies. Lloyd’s Register had surveyors for steel testing duties working in Port Talbot at the time the site, then known as Abbey Steelworks opened in 1951. The organisation’s expertise in metallurgy and its ongoing research into materials continues to inform safety standards today. A long-established partnership between Lloyd’s Register Foundation and The Welding Institute (TWI) is aiming to ensure the reliability and integrity of materials, by supporting the work of PhD students studying at the National Structural Integrity Research Centre (NSIRC), a state-of-the-art postgraduate engineering facility in Cambridge, UK.

List of Surveyors, 1950-51

In July 2021, The Maritime Executive reported that a surge in the price of steel was beginning to have an impact across the shipping industry: “Shipbuilders are expected to experience the strongest pressures, but the rise in the component price is also expected to cause an increase in the price of newbuilds and is even impacting the ship recycling sector”. [3] With plans to replace Tata steel’s blast furnaces at Port Talbot with electric arc furnaces, and continued war in Ukraine, the future safety and economics of steel production and impact on shipbuilding is entering a new and ever more turbulent phase.

Further Reading:

From the archive: Port Talbot's steelworks over the years.

17_jan_safety_first.pdf (aist.org)

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Lloyd’s Register Group or Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

- [1] Lloyd’s Register - 250 years of service, Nigel Watson (Lloyd’s Register, 2010)

- [2] Shipbuilding steels: from history to the present day (metinvestholding.com) – accessed 19/01/24

- [3] Surging Steel Prices Hurt Shipbuilders While Driving-Up Scrap Values (maritime-executive.com) – accessed 19/01/2024