Monday, July 16 2018

Cataloguing and exploring LR's expansive collection as a part of Project Undaunted never fails to present a wealth of fascinating stories from the heroic to the bizarre. It was while sifting through the correspondence, survey reports and plans for the port of Quebec that I came across records for a ship with a significant but little-known history. Beginning her life as a wooden ship for the trade between Britain and India under the name Buffalo, she would be repurposed, altered, and pass ownership many times; in Canadian history she would gain fame as Robert Kerr, 'the ship that saved Vancouver. '[1]

In 1865 the shipbuilder Narcisse Rosa, of Hare Point, St. Roche, Quebec began construction of Buffalo; a wooden ship with a gross register tonnage of 1202 and measuring 190 feet in length.[2] Built for the trader Robert Kerr & Sons of Liverpool, she was swiftly renamed Robert Kerr whilst in the shipyard, taking to the water with a Lloyd's Register class of A1 for 7 years.[3] For some time afterwards she became engaged in the Anglo-Indian trade, passing into the ownership of H. Fernie & Sons in 1876, altered to a schooner in 1879, sold on to H. K. Waddell, and again converted back to a ship in 1881.[4] Under the ownership of Waddell the decision was taken to employ her for the trade between Britain and the Pacific coast of North and South America. Under Captain Edward Edwards Robert Kerr departed Liverpool on 2 October 1884 bound for the northwest. This was to be the start of a gruelling eleven month journey and the last time she would see European shores. Battered by tropical heat, insubordination and outbreaks of disease her journey round Cape Horn and up to Panama had been fraught with disaster. With the death of her captain in August, and the running aground of the ship near the San Juan Islands, Robert Kerr was towed into the fledgling settlement of Vancouver, British Columbia on 7 September 1885.[5]

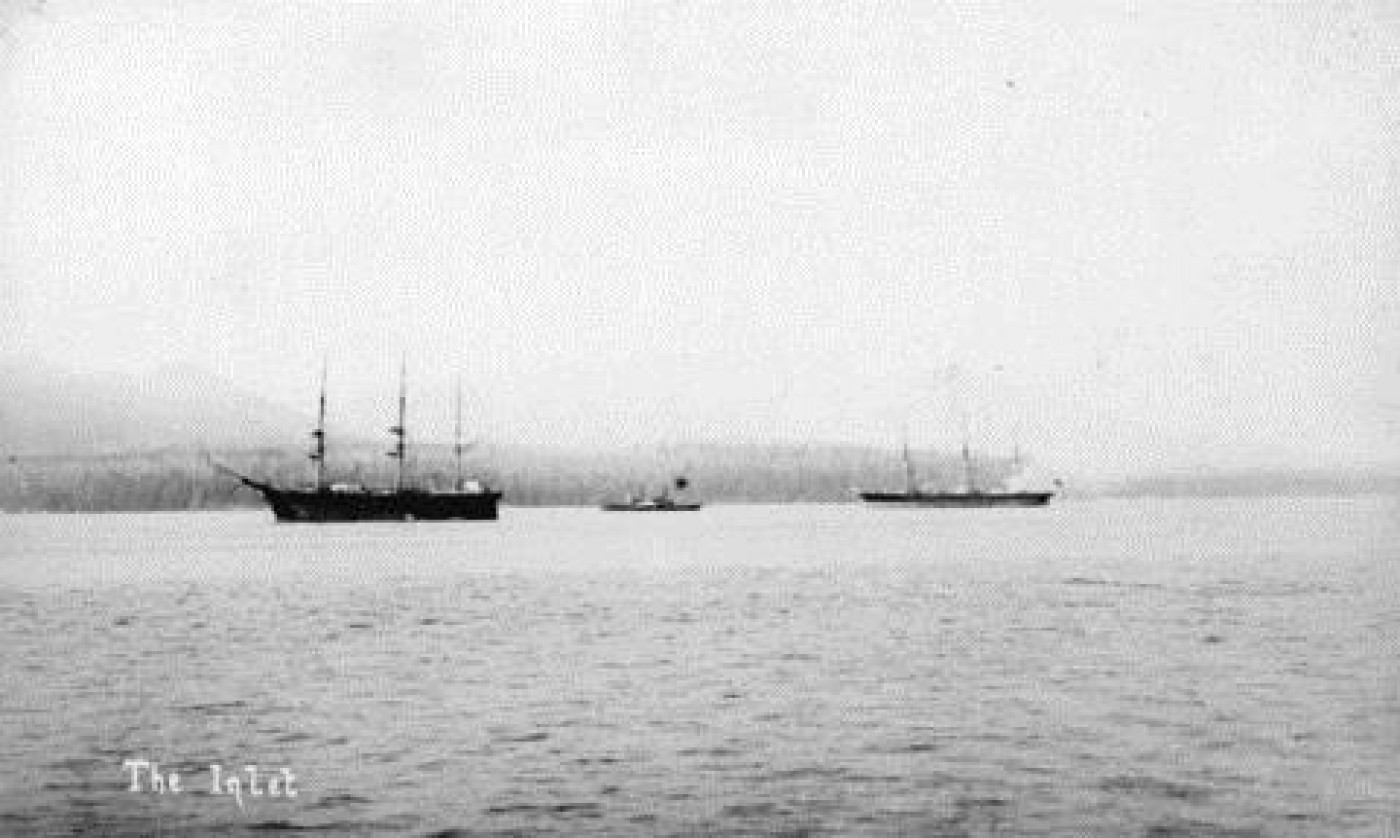

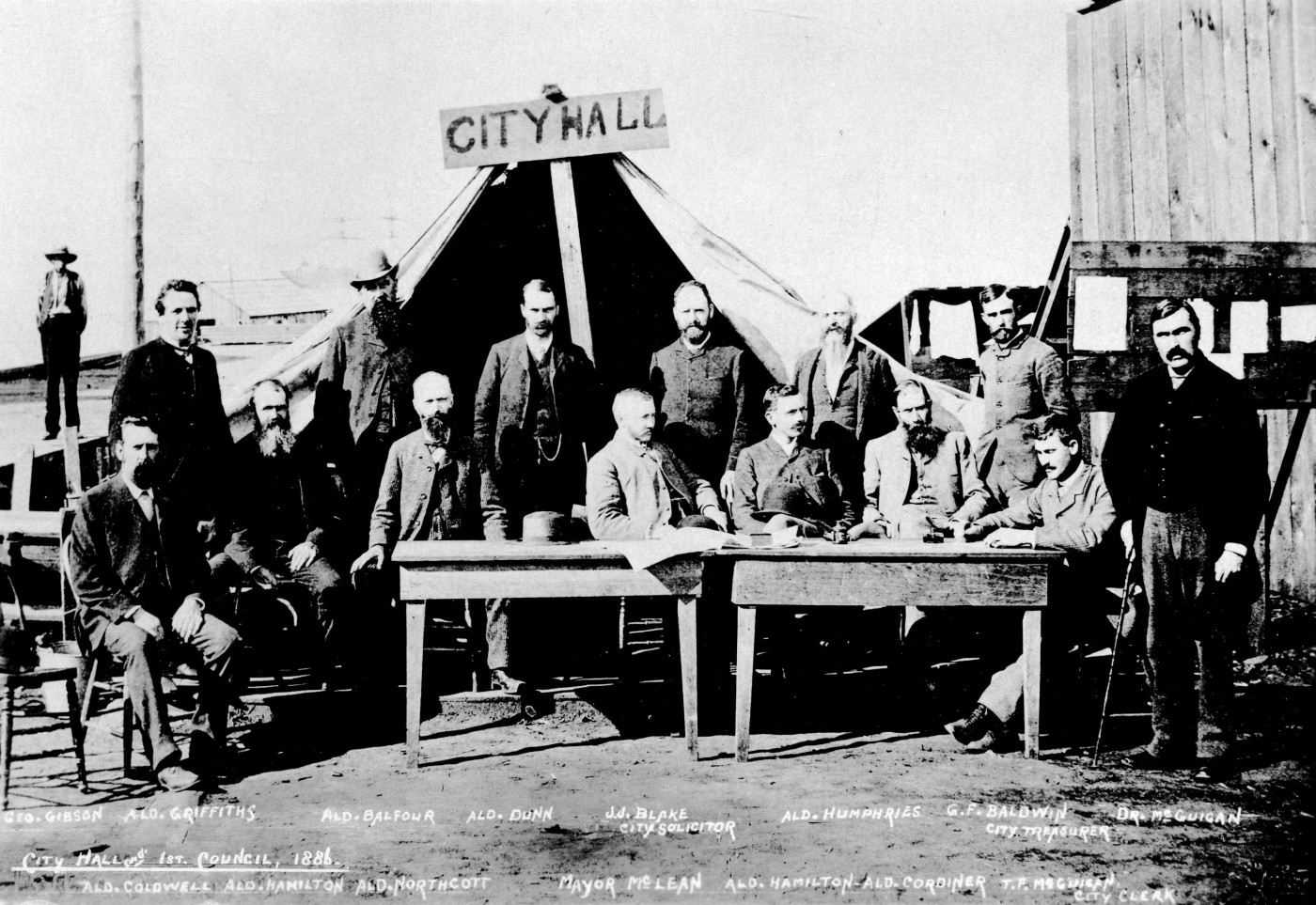

Laid up in Burrard Inlet Robert Kerr was examined on the request of her owners. Her damage sustained on the voyage from Liverpool proved too costly for the Underwriters, and so the decision was taken on their advice to sell her at a loss. Her crew were also paid off and it was here that Joe 'Seraphim' Fortes disembarked and chose to start his new life in Canada; he would later become the city's first official lifeguard and is a much-loved character in Vancouver's history. Not long after, Robert Kerr was purchased by Captain William Soule, superintendent of the Hastings Mill. A few months later on 6 April 1886 Robert Kerr displayed her signals and rang her bell in celebration of the incorporation of Vancouver as a city. Just over two months later Robert Kerr's bell would be rung again; this time as an alarm.

On Sunday 13 June 1886 labourers for the Canadian Pacific Railway worked to clear a dense area of forest to prepare for the laying of track to the West of Vancouver. To consume the mass of felled trees quickly the workers used clearing fires. All day high winds from the Northwest had fanned the flames. From 1 o'clock people were unable to make their way through the city as thick smoke began to pour heavily into the streets. At around 2:30 pm the winds rose to a gale that blew the fires toward the timber frame houses of Vancouver; by 4 o'clock only four houses would be left standing.[6]

The weeks preceding the fire had been clear and dry, this coupled with the use of timber in the construction of the city's buildings contributed to the swift destruction of Vancouver. One of the first buildings to catch light were the stables near to the Colonial Hotel. Though an alarm was quickly raised few took notice, the fire sweeping rapidly toward Carroll Street in the city centre. Within a matter of minutes the entire western portion of the city was ablaze; almost every road described as 'an avenue of fire.'[7] Equipped only with fire buckets, axes and shovels the city's two week old voluntary fire brigade soon realised they were unable to check the advance of the blaze and ran ahead to warn residents to evacuate. Already merchants were hurriedly engaged in loading horses and carts with business assets; and the streets were littered with possessions too cumbersome to carry. Panic erupted as the masses fled to the outskirts of the city, or took their chances jumping into the waters of Burrard Inlet. Some took advantage of the confusion and went directly to the unattended saloons and warehouses, many a man seen in the streets making off with 'a keg of beer on his shoulders and as many bottles of liquor as he could appropriate.'[8] Others were seen sitting in the taverns and public houses 'completely hemmed in by the fire and apparently oblivious of their surroundings, drinking liquor.'[9] Men, women and children were forcibly placed onto rafts, and dozens of Squamish canoes heroically plucked helpless Vancouverites from the inlet.

During the ordeal Robert Kerr had been blown from her mooring and had set an anchor in the harbour close to the shore, as depicted in the map of the fire by city archivist Major J. S. Matthews. In the gale the waters had become rough and treacherous and a large group of people clinging to makeshift rafts began to paddle toward the safety of the ship. The exact details of what happened next are unclear. The first issue of The Daily News following the fire describes how a large number of people reached a ship anchored in the harbour (most probably Robert Kerr) and were refused entry by the vessel's watchman; a man allegedly of “insect authority”. The people then proceeded to threaten him before being admitted on board.[10] What is certain is that over two hundred people found refuge on board Robert Kerr and from her decks watched in horror as the city of Vancouver was raised to the ground.

By 6 o'clock the flames began to die down and the victims were able to land ashore and begin the search for survivors. The exact death toll is unclear with estimates as high as fifty. In the aftermath of the disaster the scale of the destruction became clear; over one thousand were now homeless and the total figure of loss reported to be in the region of $500,000.[11] In the pioneering spirit of the Vancouverites construction of her new buildings commenced just four days later; this time out of brick. As money from relief funds flooded in Vancouver re-emerged from the ashes.

For decades afterwards Robert Kerr continued to be a feature on the waters surrounding Vancouver. After the fire she acted as a temporary residence for Captain Soule and his family while their home was being rebuilt. On 3 October 1888 Soule sold her to the Canadian Pacific Railway for $7000, where she was rapidly converted for use as a coaling tender to the CPR fleet.[12] As a hulk she worked tirelessly to bring thousands of tons of coal from Vancouver Island directly to the ships of the CPR. Robert Kerr finally met her end on 4 March 1911 on the reefs to the North of Thetis Island. During the night she had been towed off course and hit the reef, quickly filling with water, sinking stern first, and taking with her 1800 tons of coal intended for the steamer Empress of India. Resting in between twenty and sixty feet of water the wreck of Robert Kerr is officially recognised by the British Columbia Heritage Conservation Act and remains to this day a popular diving site. On 4 March 2011, a century after her loss, the Underwater Archaeological Society of B.C. replaced an existing plaque marking her wreck. Though no longer visible above the surface of the waves Robert Kerr's legacy lives on as 'the ship that saved Vancouver.'

- [1] British Columbia Historical News, Volume 19, No. 3, 1986, David Wynne Griffiths, 'The ship that saved Vancouver', pg. 18

- [2] Quebec Survey Report 770, April 1865-May 1866

- [3] Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping from 1st July 1866 to 30th June 1867

- [4] British Columbia Historical News, Volume 19, No. 3, 1986, David Wynne Griffiths, 'The ship that saved Vancouver', pg. 18

- [5] British Columbia Historical News, Volume 19, No. 3, 1986, David Wynne Griffiths, 'The ship that saved Vancouver', pg. 18

- [6] The Quebec Saturday Budget, 19 June 1886, pg. 2

- [7] The Toronto News, 16 June 1886, pg. 1

- [8] The Toronto News, 16 June 1886, pg. 1

- [9] The Toronto News, 16 June 1886, pg. 1

- [10] The Daily News, Vol. 1, No. 12, 17 June 1886, pg. 1

- [11] The Daily Argus, 16 June 1886, pg. 1

- [12] Vancouver and Beyond: Pictures and Stories from the Postcard Era, 1900-1914, Fred Thirkell, pg. 19