Sunday, November 11 2018

The reasons for the First World War are complicated and have been fiercely debated by historians. In the final episode of Blackadder Goes Forth, Blackadder, Baldrick and George discuss why the war started and, in its essence, they do perfectly summarise the causes.

Baldrick: I heard that it started when a bloke called Archie Duke shot an ostrich 'cause he was hungry.

Edmund: I think you mean it started when the Archduke of Austro-Hungary got shot.

Baldrick: Nah, there was definitely an ostrich involved, sir.

Edmund: Well, possibly. But the real reason for the whole thing was that it was too much effort not to have a war.

George: By Golly, this is interesting; I always loved history...

Edmund: You see, Baldrick, in order to prevent war in Europe, two superblocs developed: us, the French and the Russians on one side, and the Germans and Austro-Hungary on the other. The idea was to have two vast opposing armies, each acting as the other's deterrent. That way there could never be a war.

But of course, there was…

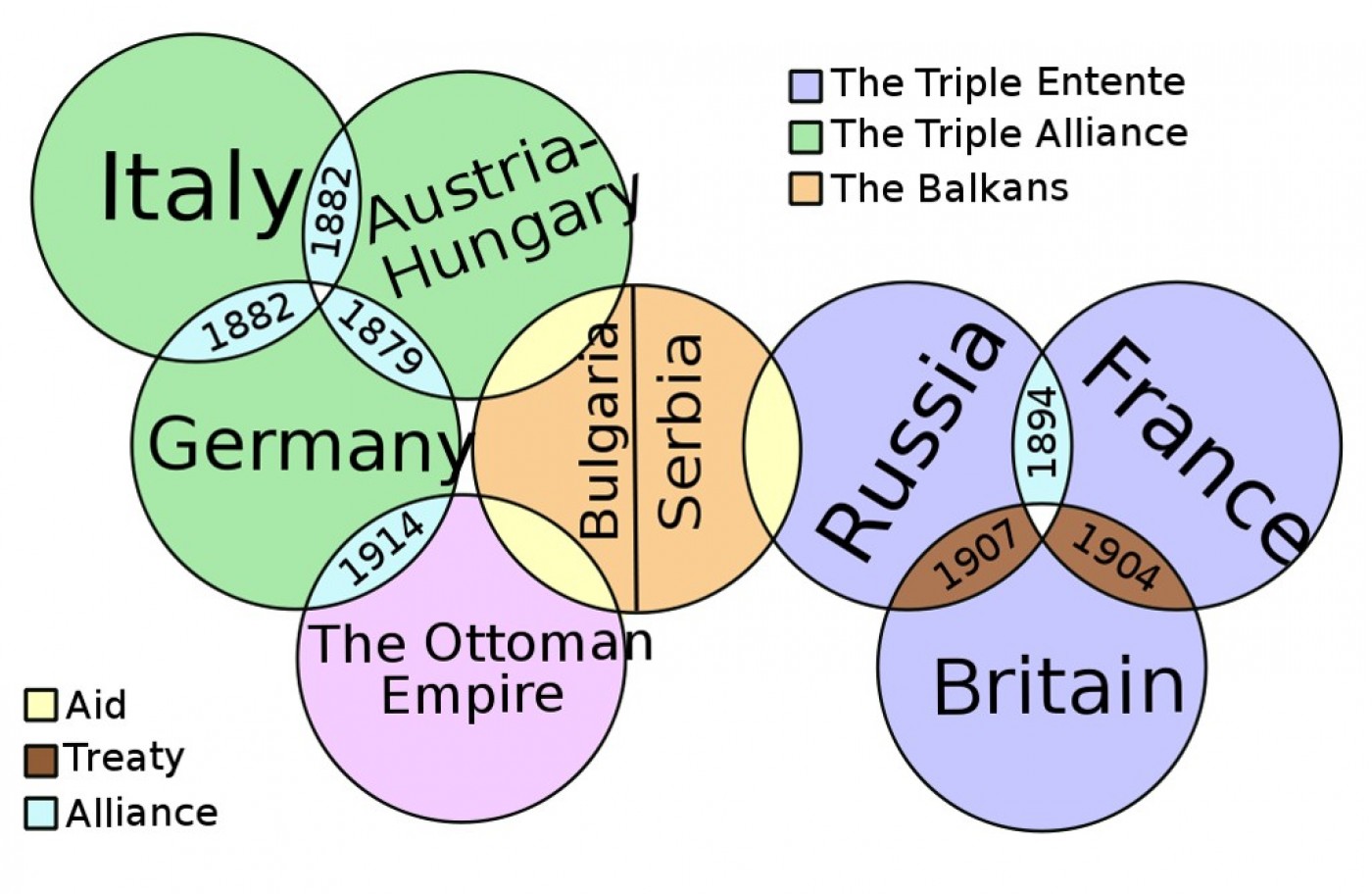

At the turn of the twentieth century, several treaties and agreements were in place between a variety of countries. As Blackadder points out, these treaties and agreements led to two blocs forming in Europe. The Central Powers - Germany and Austria-Hungary (Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria during the war) – formed when Germany and Austro-Hungary signed the Dual Alliance in 1879. It was signed to prevent or limit war, that if one was attacked by Russia, the other would support and that if one was attacked by another European state they promised benevolent neutrality. France, Russia and Britain formed the Triple Entente following the signing of various alliances between the three countries that settled old colonial disputes, economic and diplomatic problems. It also meant that if countries were attacked or threatened by others then they would come to their aid.

Whilst treaties were being signed, Britain and Germany had been involved in a Naval Arms race. Following the unification of Germany in 1871, Germany wanted to modernise and create a naval fleet that would be able to compete with the Royal Navy and force Britain to make diplomatic concessions. Historians have argued that both sides had a desire to test the strength of their navies through a decisive battle. For Britain, it was seen that there would be a second 'Trafalgar'.

By 1914, there was a feeling around Europe that war felt inevitable. The spark that led to the outbreak of war was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, on the 28 June 1914 in Sarajevo. They had been assassinated by Gavrilo Princip, a member of the Serbian Black Hand gang, which led to a worsening in Serbian and Austro-Hungarian relations. Eventually Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on the 28 July 1914 and from this declaration of war, all previous treaties, agreements and plans fell into place. Russia in support of Serbia declared mobilisation against Austria-Hungary. Germany issued an ultimatum to Russia to not support Serbia and to France to not support Russia. Germany feared that if they attacked Russia they would also have to fight France. After Russia fully mobilised on the 30 July, Germany declared war on Russia on the 1 August. On the 2 August, Germany attacked Luxemburg and declared war on France on the 3 August. On the 4 August Belgium refused to allow German troops through into France so they declared war on Belgium leading Britain to declare war on Germany in defence of Belgium.

The war would last for four long, gruelling years. It would see a complete modernisation in warfare with the use of new tactics and weapons including tanks, aircraft, gas and artillery. The human cost of the war was around 35 million casualties including 16.5 million deaths and 20 million wounded (both military and civilian). Battles including the Somme, Passchendaele and Jutland have been firmly embedded in the national psyche and the horrors of the trenches have been well documented as well as the effects the war had on people and countries.

The Role of Lloyd’s Register during the First World War

With the outbreak of war several ships were requisitioned by the government for military service. Passenger ships would be used to transport soldiers and supplies, smaller vessels were used for mine-laying or clearing. Shipyards were instructed to prioritise military requirements and the society found itself busier than ever carrying out surveys and classification work. The Admiralty invited the society to provide advice for new types of auxiliary vessels built by civilian yards, recognising Lloyd’s Register’s expertise particularly with lightly built vessels including minesweepers and gunboats. Over a thousand vessels like this were built under Lloyd’s Register survey.

With the incredible expertise found throughout Lloyd’s Register, the government seconded several members of senior staff including Wescott Abell, Chief Ship Surveyor, who became the technical advisor to the controller of shipping. Secondments and enlistment meant that the society was worked to its limits as they were short staffed but carrying out more work than before. The government eventually made jobs at Lloyd’s Register reserved occupations, meaning that members of staff were returned to their jobs and were exempt from military service.

British shipyards had been turning out 60% of the world’s shipping before the war could not supply enough ships. In 1916, the government took control of shipping and looked to build ships in other countries including America, Canada and Japan. This led to shipbuilding in these countries to grow by an incredible rate.

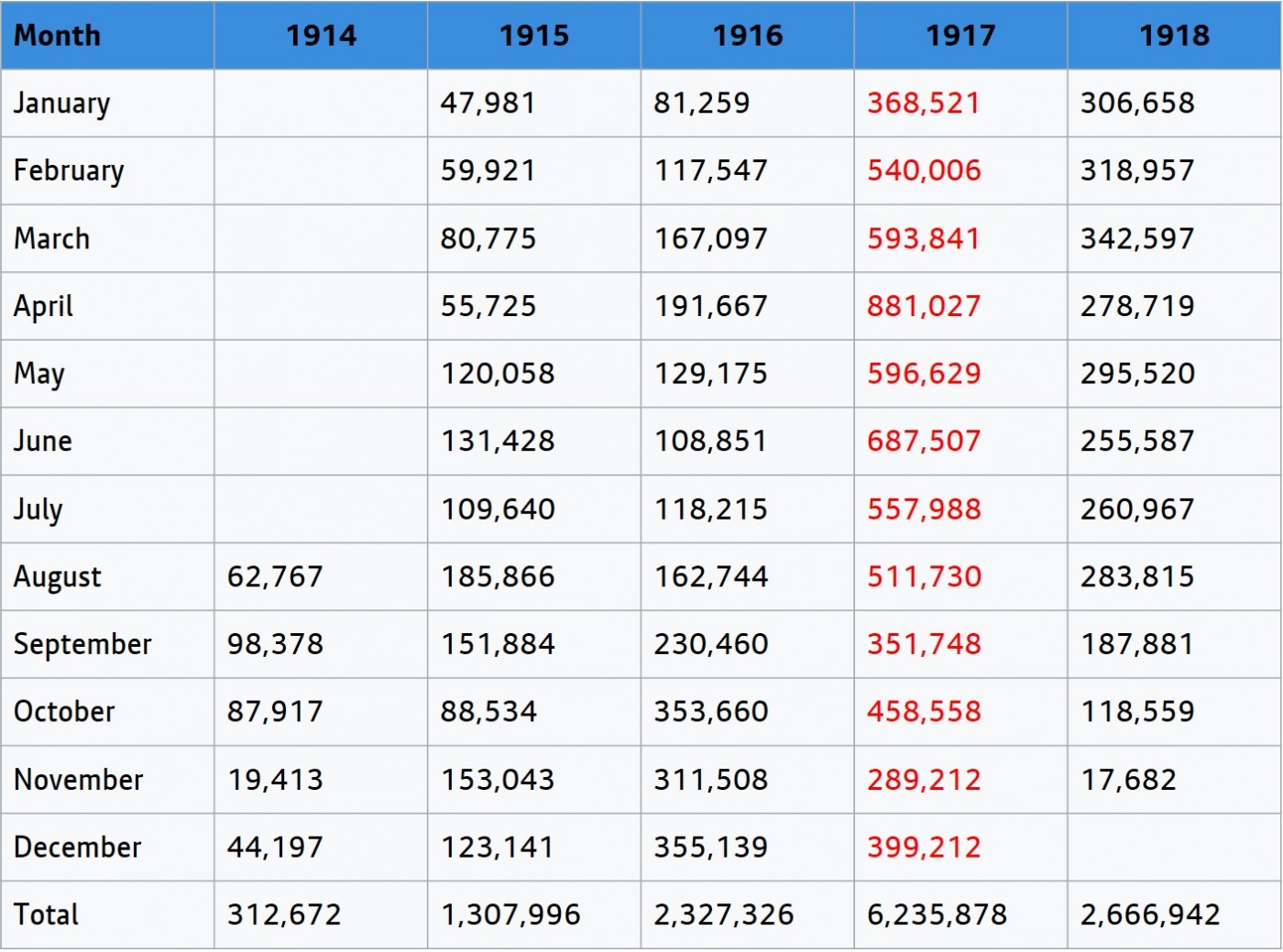

A significant part of German naval strategy during the war was their infamous U Boat campaign. The aim was to use U boats to attack allied trade routes and ships in order to force them into a surrender. In 1915, the Germans had adopted ‘unrestricted submarine warfare’ after realising that the war would not be won quickly and harsher measures needed to be in place in order to win. International naval law had stated that merchant ships sailing under a neutral flag could be stopped and searched for contraband but they could not be sunk unless the passengers and crew were safely on shore. However, ‘unrestricted submarine warfare’ ignored this and turned the waters around Great Britain and Ireland, including the whole of the English Channel, into a War Zone with neutral vessels also at risk. The German U boats sank nearly 5000 ships across the war, with many of them were classed by Lloyd’s Register and appeared in the Register Books.

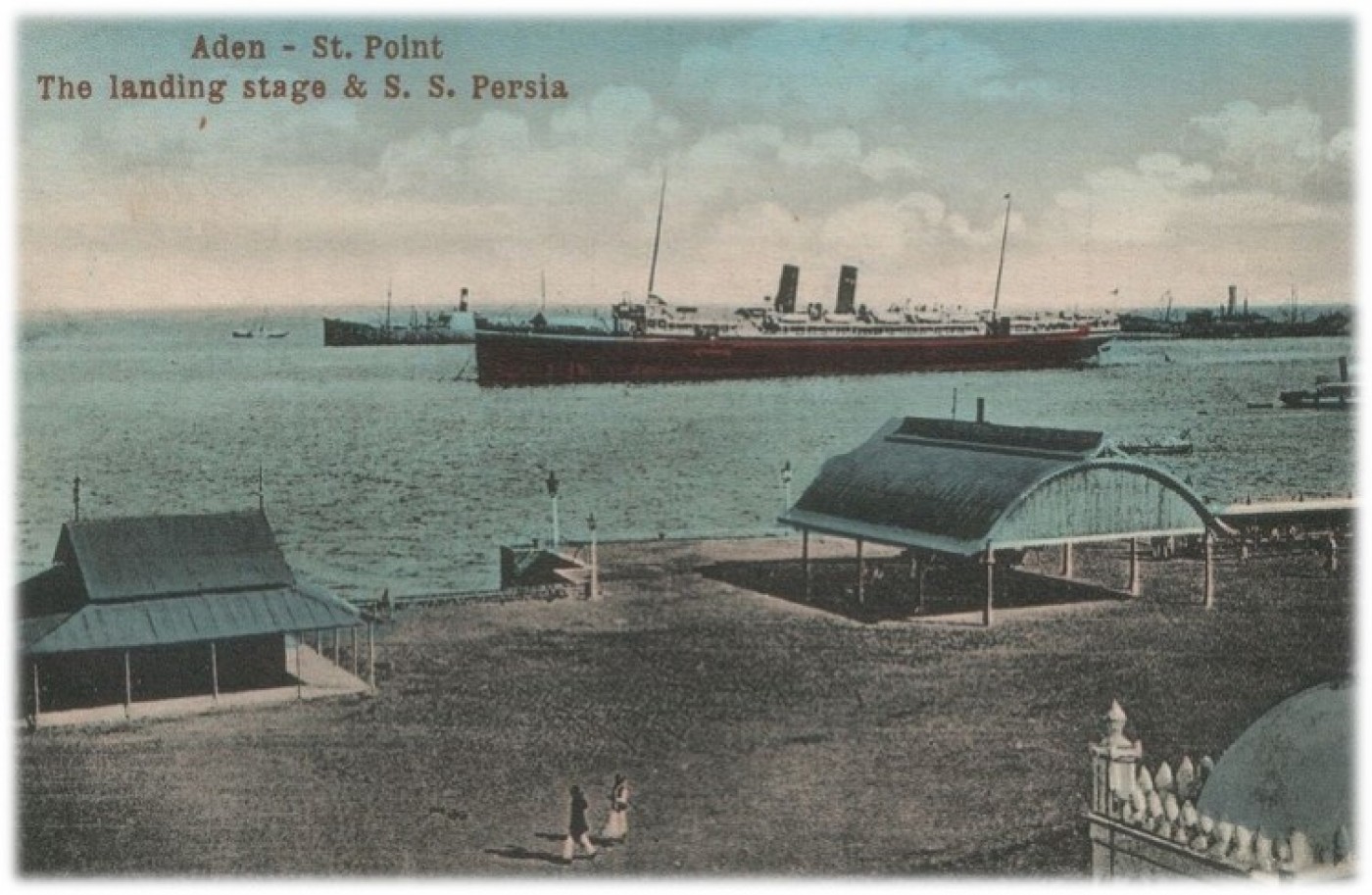

On the 30 December 1915, the Persia was torpedoed by the German U-boat SM U-38 off the coast of Crete whilst the passengers were having lunch. She sank within 10 minutes, killing 343 of the 519 aboard. This attack was highly controversial as it broke naval international law but the Persia openly displayed a British rather than neutral flag and therefore fell under unrestricted submarine warfare.

From understanding the German strategy of unrestricted submarine warfare, we can see why the Register Books would have been a valuable tool for them as they were essentially a list of active merchant ships across the world with details on tonnage and ports. Restrictions were therefore put in place by the authorities on the overseas circulation of the Register Book to prevent them from falling into enemy hands. Inevitably, however, copies of the Register Book fell into enemy hands and the German Navy made sure that a copy was put in every ship and submarine. The book featured in a German propaganda film entitled The Enchanted Circle. The film follows the crew of U 35 and highlights the successes of their U boat campaigns. In the film the commander of the U 35, who was responsible for sinking 194 ships, is shown crossing off the name of his most recent ‘kill’, the Brisbane River which sank on 17 April 1917.

Joined Colours

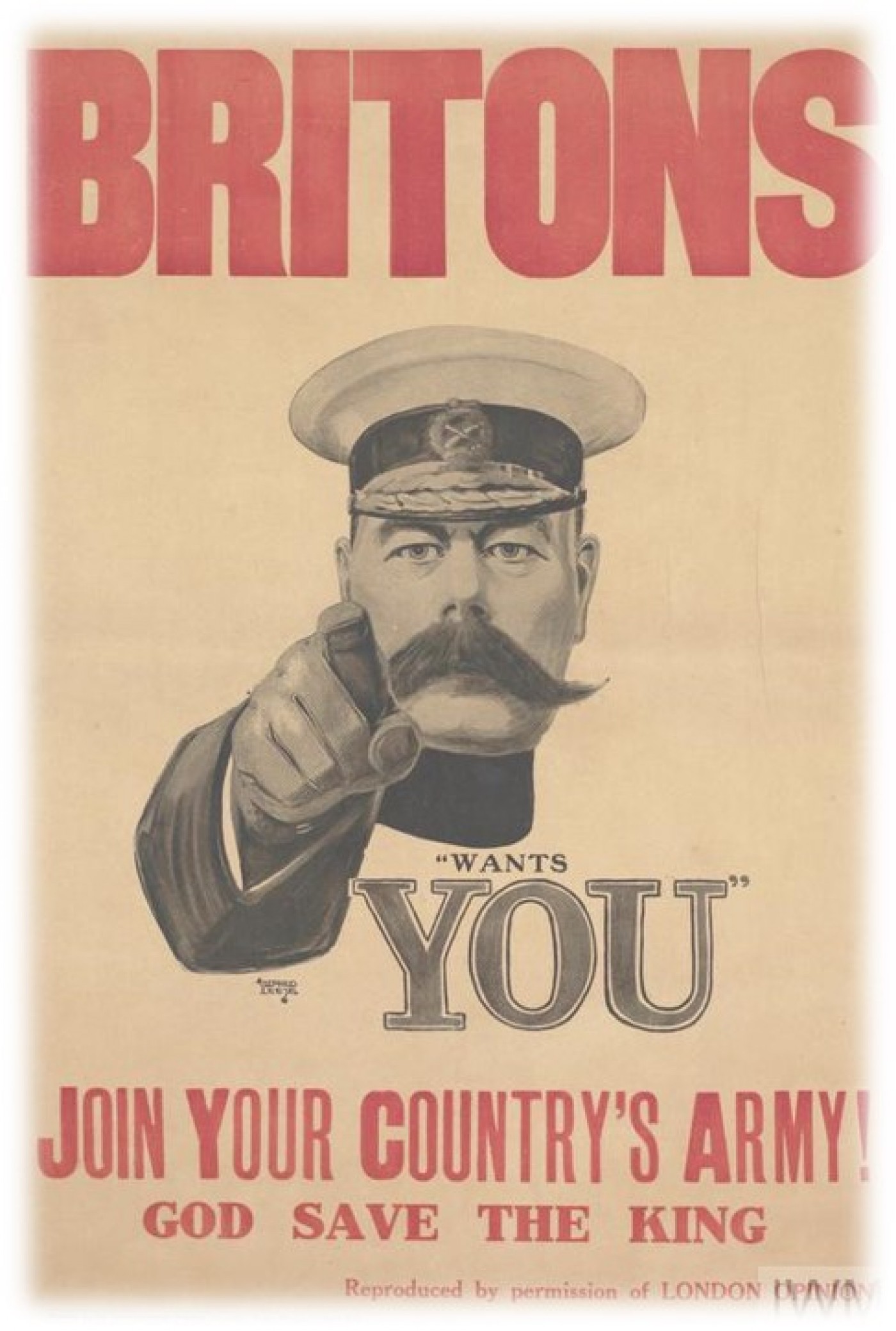

When war broke out in 1914, it was believed that there were around 5.5 million men in the country of military age, with an additional 500,000 turning 18 every year. The British Army had around six infantry divisions, one cavalry division, 14 territorial force divisions and 300,000 soldiers in the reserve army. At the outbreak of the war, the Army aimed to recruit 100,000 men. Nearly half a million men signed up within two months as volunteers, with an additional 250,000 underage boys joining up.

Many joined colours with their friends, colleagues, team mates, meaning that they could serve together in the same battalion rather than being spread across the country. These became known as ‘pals battalions’ and became incredibly popular across the country. The problem with this type of battalion was that the entire male population of a town or village could be wiped out in one battle. Joseph E Russell joined the The Stockbroker’s Battalion, made up of men who worked in the Stock Exchange and other City of London firms.

Kitchener had insisted from the outbreak of war that Britain needed a large army to last a long war. By 1915, the number of soldiers was diminishing and there were not enough volunteers to make up the number. Though the British government had historically been opposed to conscription, in the Autumn of 1915, the Derby Scheme was launched. This was to determine whether British manpower goals could be reached by volunteers alone or if conscription was necessary. All eligible men between 18-41 who were not ‘starred’ had to make a public declaration. This led to many men volunteering as they did not want to be seen as being ‘fetched’ for service. Men canvassed their towns looking for new recruits-these were usually men who could not fight including the older generations who had previously been to war. Though over 300,000 men were recruited through this scheme, large percentages of single and unmarried men still refused to fight. Conscription was therefore introduced in 1916 through the Military Service Bill. Initially only single men and childless widowers were called upon but this was soon extended to married men.

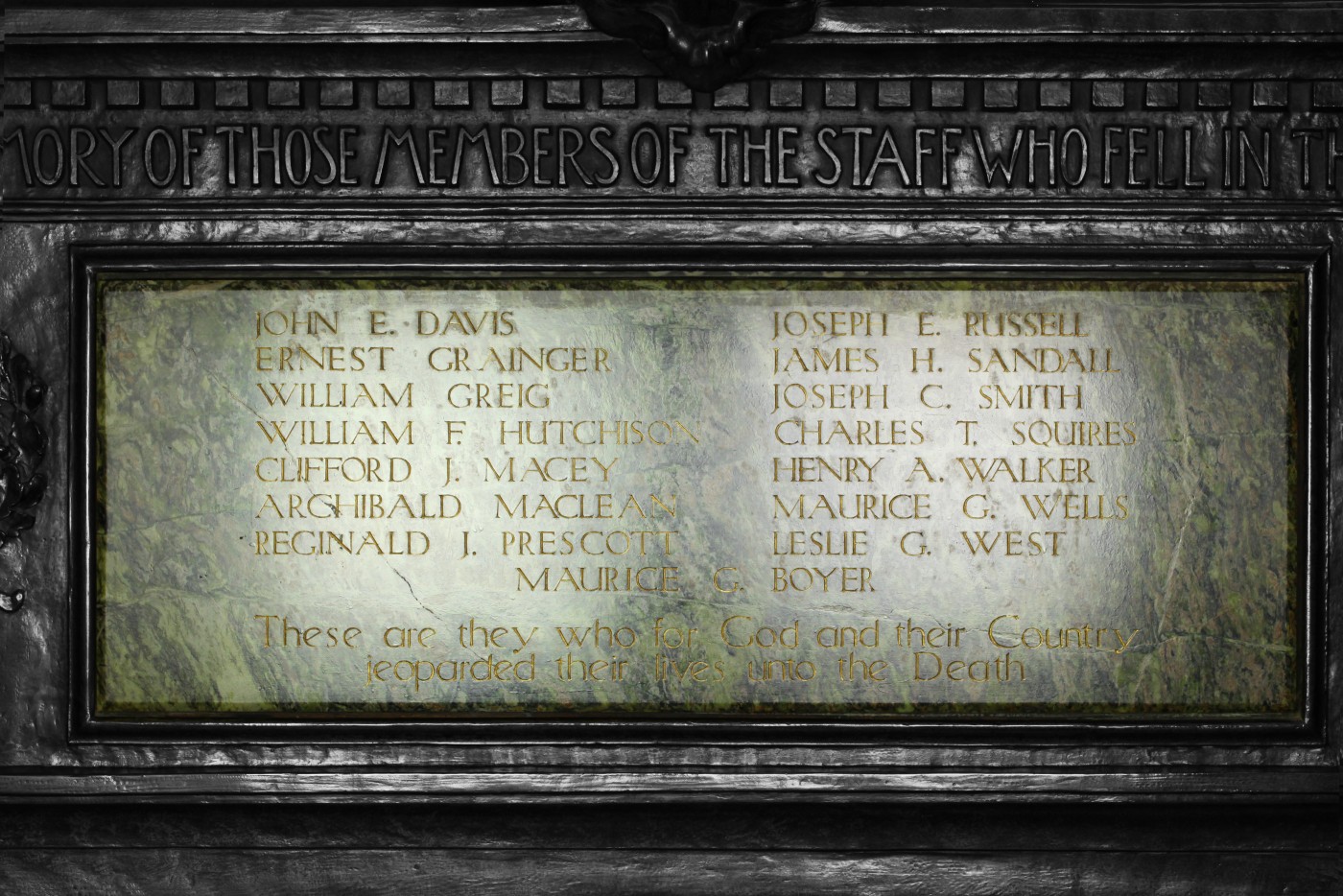

With the introduction of conscription there were many organisations and jobs that could not afford to lose their workforce to the war. Many of these places became reserved occupations meaning that their employees were exempt from military service. This could include professions involved in the railways, clergy, teachers, doctors and some agricultural labourers. Lloyd’s Register was included in this as the expertise of surveyors and staff were needed in the construction of new ships (shipbuilders and dockers were also often exempt from service). However, 108 men from Lloyd’s Register did join colours and 15 died during, or because of, the war. These 15 are listed on our memorial and you can learn more about them here.

By using our staff bibles we can find the men who did go and fight and details on when they joined colours and when they returned to Lloyd’s Register.

Across the country, women were replacing men in various jobs, most famously in the munitions factories. This was the same at the Lloyd’s Register HQ in London. Though women were employed at Lloyd’s Register globally, there were none in employment at 71 Fenchurch Street. During the war, women were employed as temporary clerks and shorthand typists. They were not allowed to collect files from the basement without a male escort who would carry the files back up for them. All the women left when the war ended and the men returned to work which was not uncommon. After returning during the Second World War, women were invited to stay as employees in the London office of Lloyd’s Register.

108 men from Lloyd's Register 'joined colours', 15 of which died and are listed on our memorial. You can learn more about the lives of the soldiers on our memorial as well as the battles they were involved in here.

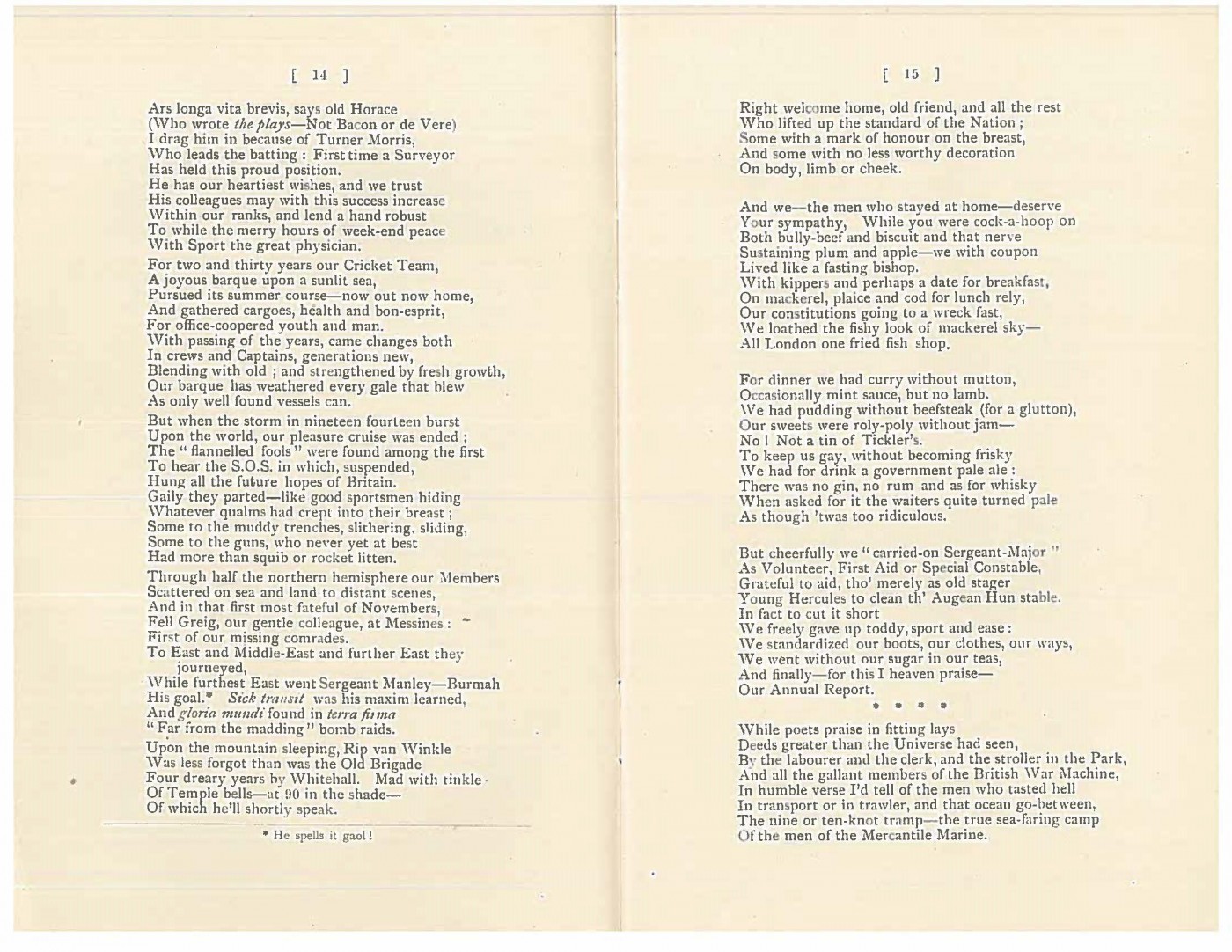

The Cricket Club

Many of the men from the Lloyd’s Register Cricket Club fought in the First World War. The Cricket Club, formed in 1882, the year of the first Ashes, was an integral part of Lloyd’s Register. It was a source of pride, passion and unity for the players as well as the organisation. As with the national teams, during the First World War, the Lloyd’s Register Cricket Club ceased playing and meeting for their annual dinner. When the first dinner was held following the war in 1919, the players and members paid tribute to their fallen comrades. It was common for the dinners to have poems written about the cricket season and so on this occasion a poem was written to commemorate the fallen as well as those who fought and returned.

But when the storm of nineteen fourteen burst

Upon the world, our pleasure cruise was ended;

The “flannelled fools” were found among the first

To hear the S.O.S in which, suspended,

Hung all the future hopes of Britain…

Through half the northern hemisphere our Members

Scattered on sea and land to distant scenes,

And in that first most fateful of Novembers,

Fell Greig, our gentle colleague, at Messines:

First of our missing comrades

The guns fell silent

On the eleventh hour, of the eleventh day, of the eleventh month, the guns fell silent across the Western Front and the war to end all wars was over. The total number of military and civilian casualties in the First World War was around 40 million. It is estimated that there were 15 to 19 million deaths and 23 million wounded.

By the end of the war, Lloyd’s Register employed over 500 surveyors and had surveyed more than 10 million gross tons of merchant shipping. Due to the work of Lloyd’s Register, the shipbuilding industry grew in America and Japan.