Monday, January 25 2021

It was quite the task trying to choose my favourite thing at Lloyd’s Register, especially as a new member of staff joining during the pandemic. Although I’ve only been able to access the archive remotely, I’ve enjoyed learning about the ships and people that are part of Lloyd’s Register’s lengthy history. With a background working with social history collections, uncovering stories about Lloyd’s Register former employees really sparked my interest, so I decided to choose the mischievous watermen who worked at the company in the 1830s as my favourite thing.

Until the 1900s, before we had the London Underground and the network of bridges that connect London today, London Bridge was only the way to cross the River Thames on land within central London.[1] Watermen provided an essential water taxi service, transporting London’s residents along the Thames in small wooden rowing boats known as wherries or skiffs[2] which could be hired at numerous stairs leading down to the Thames. According to John Stow’s publication A Survey of London in 1598, when the population of London was around 200,000, approximately 3000 men were working as Thames watermen. Being a waterman was skilful work and required an in-depth knowledge of tides to ensure swift journeys along the Thames.[3]

In the 1830s, Lloyd’s Register employed two watermen who were tasked with rowing surveyors to and from ships on the River Thames. Waterman James Buxton belonged to the Underwriter’s Register, whilst Nathaniel Archer worked for the Shipowner’s Register (this was a time when two rival registers existed, which you can learn more about here). Much like Lloyd’s Register’s messengers, watermen were expected to wear engraved, silver-plated badges. These are the original badges that Buxton and Archer wore as part of their uniforms:

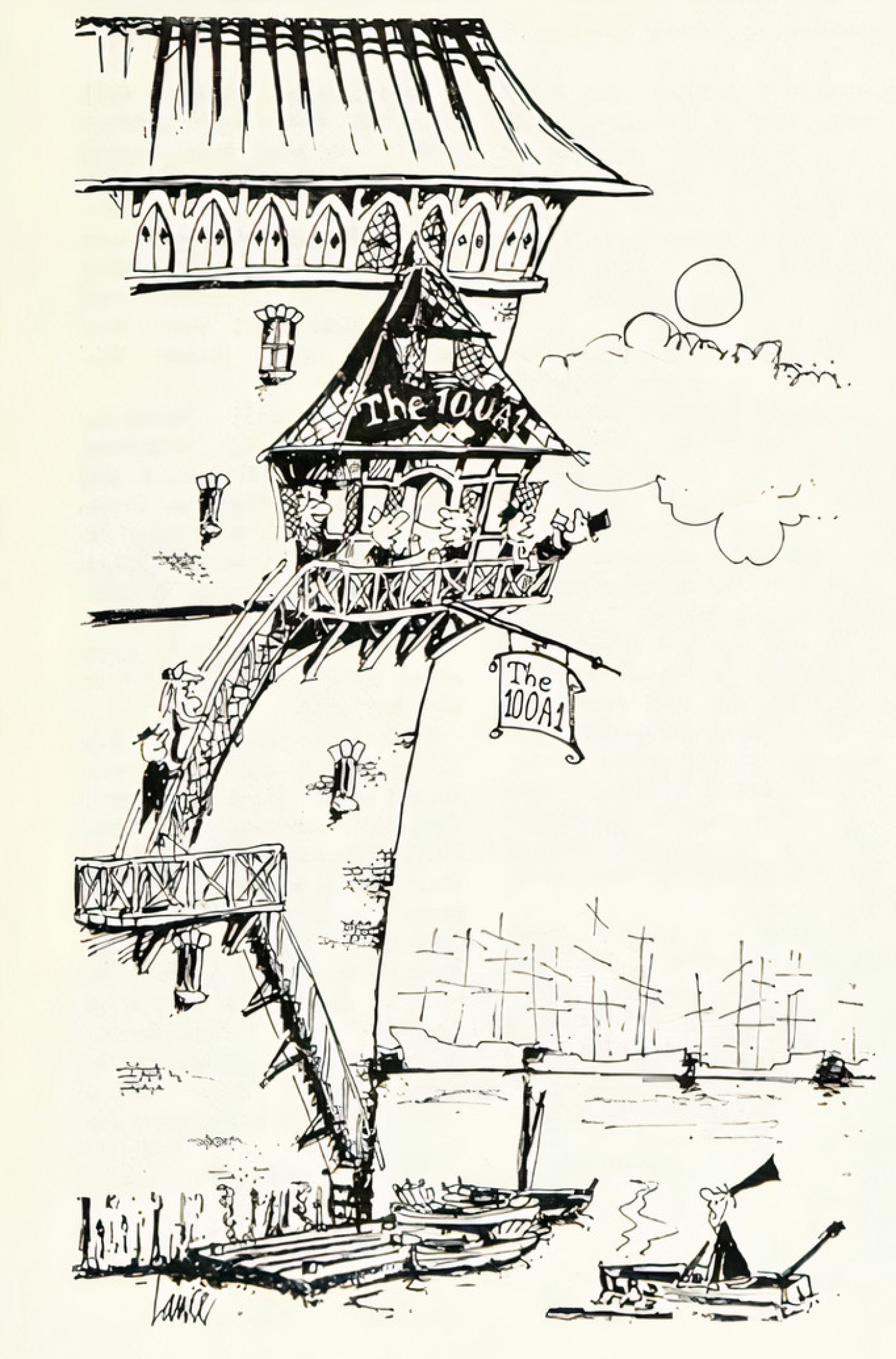

Nathaniel Archer was dismissed from the Shipowner’s Register in 1839 under rather amusing circumstances. It was discovered that the medical certificate, which Archer used to justify leaving his apprentice unattended, was a forgery. Archer was, in fact, very well indeed and running his beer shop during work hours![4] A cartoonist named Lance made light of the situation with this humorous, satirical drawing titled “Nathanael Archer’s beer shop”, jokingly referring to the beer shop as “The 100A1” (see our Classification information sheet here for a detailed explanation of the 100A1 ship classification).

I like to think that Archer was taking advantage of the 1830s Beerhouse Act. This allowed licence holders to brew and sell beer and extended the legal opening hours of public houses from 15 to 18 hours a day, leading to an increase in business competition and the lowering of beer prices. The end goal was to lessen the public’s consumption of stronger drinks such as spirits, but many viewed this relaxation of regulations as promoting drunkenness.[5] Thankfully we have no evidence in the archive to suggest that Archer was drunk on the job!

I hope to learn more about Lloyd’s Register’s extensive collection during my post here as Collections Assistant. I’m eagerly awaiting the return to normality so I can get stuck in working in the archives in person and sharing more stories like these.

- [1]Peter Stone, Thames watermen and ferries | The History of London [accessed 19 January 2021]

- [2]Royal Museums Greenwich, Passenger vessel; Skiff; Greenwich waterman's skiff - National Maritime Museum (rmg.co.uk) [accessed 20 January 2021]

- [3]Peter Stone, Thames watermen and ferries | The History of London [accessed 19 January 2021]

- [4]Nigel Watson, 2010, Lloyds Register 250 years of service [accessed 18 January 2021]

- [5]History House, What was a beerhouse? (historyhouse.co.uk) [accessed 19 January 2021]