Wednesday, February 08 2023

This article was written for the Rewriting into Maritime History project by Dr Nina Baker, an independent engineering historian specialising in the history of women in engineering and was appointed an OBE in the 2023 New Year’s Honours’ list, for services to the history of women in engineering. It explores the presence of women in shipbuilding on the Clyde during the First and Second World Wars.

It is 1942. Britain is struggling and needs every hand available to help turn the tide of the Second World War. An 18-year old working class girl gets up at 6.30 a.m. to get 2 trams from her home in Glasgow’s East End to John Brown’s Shipyard in Clydebank for her 8 a.m. shift as an electrician fitting electrical systems to the ship that would become the destroyer HMS Vanguard. After ten gruelling hours’ work she won’t be home again until 8p.m.

At 18 years old, Janet Harvey was the youngest of only four women to be trained as an electrician. She and her colleagues had 3 months training at Glasgow’s Royal Technical College, which was a lot at the time, when compared to many other industrial or uniformed services roles available to women. She was first sent to Harland and Wolff’s yard in Govan Cross and later to John Brown’s in Clydebank. Janet and her colleagues would spend the rest of the War years scrambling up and down precipitous ladders with their toolboxes, fitting the wiring throughout the ship.

Harland & Wolff 1918 © Imperial War Museum Q 110082

Women have probably always had roles in some aspects of shipbuilding, such as the french polishing of furniture and panelling, or rope-making, but the mass employment of women in the traditionally male-majority trades relating to the actual building of ships only came with World War 1 (WW1). Work in the manual skilled trades (blue collar) is colloquially known as work “on the tools”, to contrast with the various office-based (white collar) roles which might also be done by working class people but also included all the classes through semi-professional drawing office staff, professional naval architects and engineers and the senior management. However, it would be decades from the time of WW1 before women were able to make significant inroads into the all-male professional roles connected with shipbuilding.

Since the majority of women doing war work in the shipyards in the manual trades were from the same working-class backgrounds as the men, there are very few records of their names, let alone any details of their lives or work to the extent that we know about Janet Harvey. This blog only looks at women working in the Clydeside shipyards which constituted about 90% of the Scottish shipbuilding industry. However, women were doing similar war work in all the Scottish shipbuilding areas, such as Aberdeen, Dundee, Fife, Leith and even the smaller ones such as Inverness. Famously, Victoria Drummond started her shipyard apprenticeship in the Caledon company’s Dundee engineering and boilerworks in 1918, before going on to become the first ever woman ship’s engineer.

First World War (WW1)

The obvious and urgent need to replace the men gone to the Front, led to ‘dilution’ with women in men’s work. The government had to push hard to enforce the law requiring firms to take on women, especially on socially-conservative Clydeside.

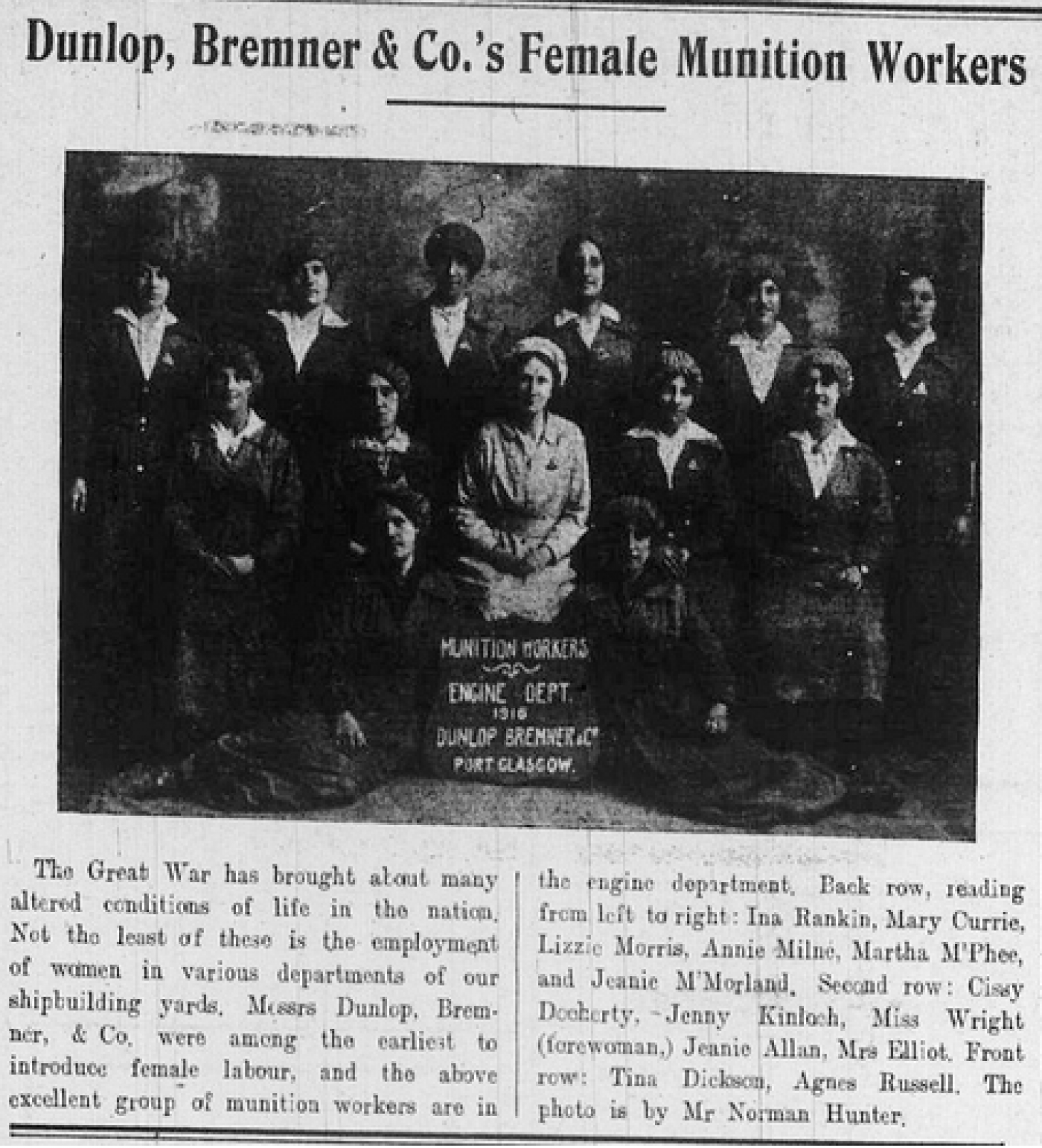

In 1916 Dunlop, Bremner & Co, of Port Glasgow, were happy to be seen in the press to be employing women in its engine shop: “The Great War has brought abut many altered conditions of life in the nation. Not the least of these is the employment of women in various departments of our shipbuilding yards. Messrs Dunlop, Bremner, & Co. were among the earliest to introduce female labour, and the above excellent group of munitions workers are in the engine department. back row from left to right: Ina Rankin. Mary Currie, Lizzie Morris. Annie Milne. Martha M’Thee, and Jeanie M’Mogland. Second row: Cissy Docherty, Jenny Kinloch, Miss Wright (forewoman.) Jeanie Allan. Mrs Elliot. Front row: Tina Dickson, Agnes Russell.”

Dunlop, Bremner & Co, of Port Glasgow, 1916

This image is a rare survival of anything that gives the names of actual women from this period, but unfortunately no more is known of these women.

Even rarer, are the letters which Jeanie Riley wrote to her soldier husband and which Fairfield Heritage have brought to light. These tell of her hard work in Fairfield’s engine shops, whilst managing to raise two children on her low wages and a small allowance that the Army sent from her absent husband’s pay. She wrote that the women “were told that the amount of work we do in three weeks would have taken the men three years, and Jamie, the men are quite mad at us”.

Although the law required such women to be sacked when the war ended, it is apparent that there were still some roles in the shipyards even in the lean years between the two world wars, as a photo taken at Alexander Stephen’s works at Linthouse in 1924 shows two women amongst a group of bowler-hatted men from the Engine Department Staff. No names are given for the women and we do not know what their work was in that department, possibly store-keeping or clerical.

Linthouse, 1924

Second World War (WW2)

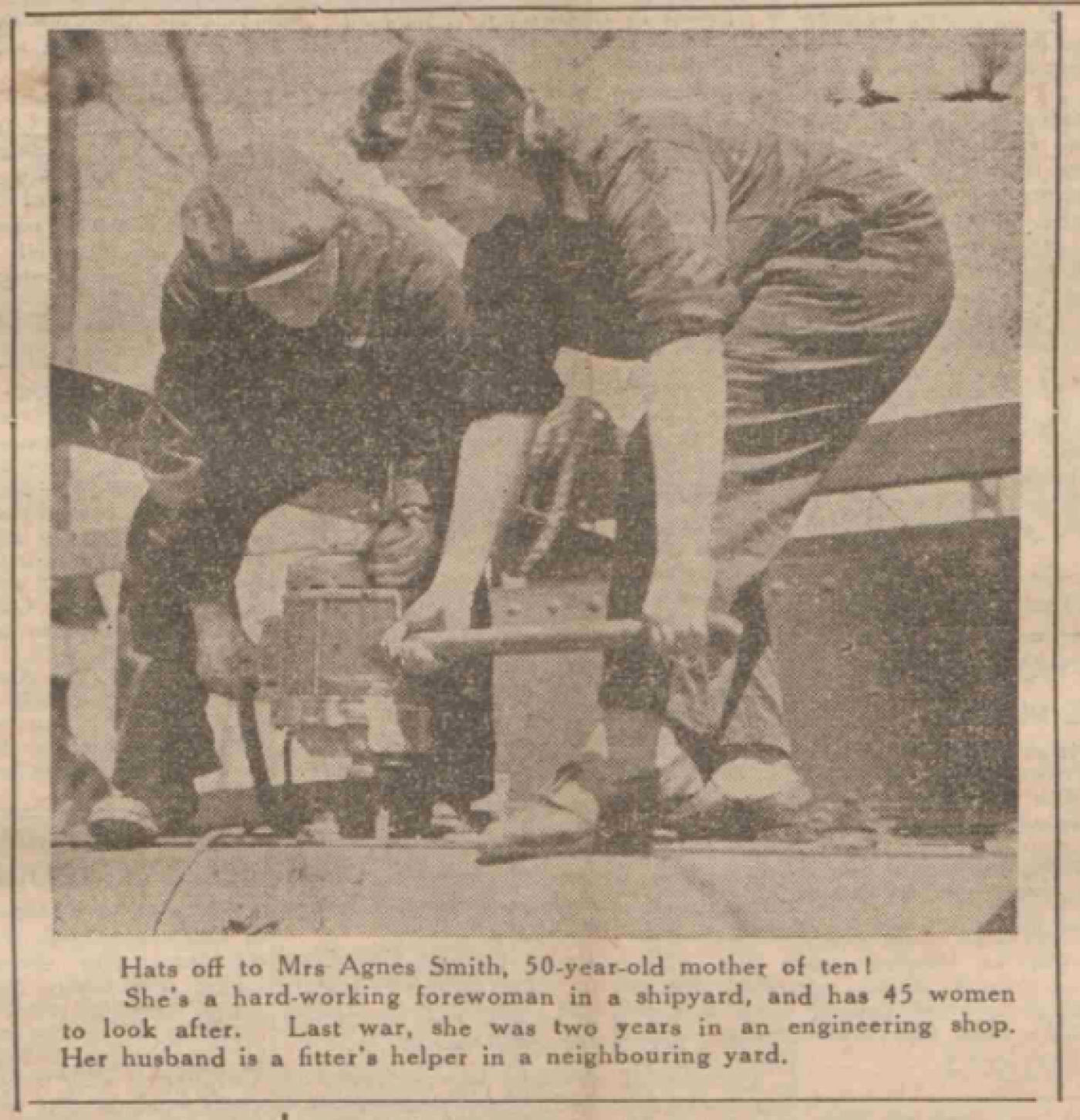

Mrs Agnes Smith is woman whom we do know served in Clydeside shipyards during WW1, but we only know that because of pictures of her when she served again, in WW2. A series of publicity photos from 1942 and similar in the press (Sunday Post 28 June 1942) reveal a little more about her. Born in about 1892, she spent 2 years in a shipyard engine shop in WW1. By 1942 she was married to a fitter’s helper in another shipyard and they had 10 children. However, despite this large family, she took work in a Greenock shipyard where she was forewoman in charge of 45 women, all of whose jobs she was said to be competent to do herself. In one photo, she is shown with a group of her workers, named as Mary Cunningham, Sadie Nairn, Agnes Smilie and Sandra Williamson, who are carrying the tools of the welder’s trade. We might conjecture that her WW1 experience was instrumental in gaining her the promotion to forewoman, but surely she would not have been the only woman with such experience.

Agnes Smith, forewoman at Greenock Shipyard Imperial War Museum © Imperial War Museum 8991 & 8991a

The Scotsman Newspaper, 1943 © The British Newspaper Archives

A 1943 report in The Scotsman newspaper, on the work of the Clydeside shipyards commented: “One of the things which struck me in a visit to a busy shipyard was the presence' of so many women, looking as businesslike in their overalls as the most representative members of the hardy ‘black squads’. They are of all ages, from grandmothers to attractive maidens. not very long away from school. One who at least looked as if she were in the grannie class was manipulating a steam hammer with a deftness of touch? which suggested that this had been her life work. Girls who can earn up to £5 or £6 a week were doing skilled work welding ships' plates, others were doing jobs in the shops which demanded not only skill, but considerable physical capacity, and many were busy in the electricians' department.” Perhaps the reporter had seen wee Janet Harvey at work.

In 2018 Janet Harvey described her WW2 work: “We worked on small destroyers such as HMS Vanguard. A lot didn’t have names when we were fitting them out, they were new. We were mates with a full-time tradesman and worked with them. They pulled the heavy cables and gave us the light jobs. We fetched for him, got him the things that he needed. Us women did mostly power boxes, where the cables come in. To me it was just like knitting. I was a knitter and it was just following a pattern: A went into there, and B, and C went there. We were very nimble with our fingers.”

Publicity efforts by the government to boost morale resulted in photographs and paintings (by war artists) of women working on the tools in many Scottish shipyards undertaking fitting, repair work, welding and rivetting. That publicity did not stop the girls being treated in what we would now consider to be an unacceptable way: "It was horrendous," Janet said. "It was awful. All the men were looking at us and whistling. It gradually quietened down and you got used to it but it wasn't an environment for young girls”.

But, as at the end of WW1, the girls and women who were so praised by the public during the war were unceremoniously sacked as the war contracts ended, and Janet and the other women were “cast aside like old rags” and dismissed without a medal or any word of thanks from the nation. Janet got a job with the Cooperative shops and then went on to manage off-licences, until she retired. However, in 2018, Janet’s service was finally recognised when she was awarded an honorary doctorate of engineering from Glasgow Caledonian University "in recognition of her outstanding contribution to the war effort with the Glasgow shipyards". She was astonished that a wee Glasgow girl with no qualifications could now be addressed as Dr Harvey!