Ballast water plays a crucial role in the stability and safety of ships. Modern ships use a system of pumps and water tanks as ballast. By adjusting the amount of water in tanks strategically placed around the vessel, the ship's officers can balance and maintain stability and an even load.

Without ballast, unladen vessels would sit too high in the water, increasing their vulnerability to adverse weather conditions. High winds and rough seas could cause the ship to heel, which in extreme cases may result in capsizing.

For more information about the history of ballast, see our story Ballast: A Hidden History on how to avoid Shipwreck.

Despite being essential to the safe and efficient operation of ships, ballast water can also pose significant risks to human health and the environment. As ships take on ballast water in one port and release it in another, they can also unintentionally transport a wide variety of organisms to different ecosystems, including algae, bacteria, and larvae.

These non-native organisms can disrupt the balance of these ecosystems and harm local species. The discharge of invasive marine species through ballast water is considered one of the biggest threats to our oceans.

To address this issue, in February 2004 the International Maritime Organization (IMO) adopted the International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships' Ballast Water and Sediments, also known as Ballast Water Management (BWM) Convention. The Convention became operative in September 2017, imposing a series of new standards on water discharge. Ships are required to install filters and disinfection systems to ensure that ballast water is properly treated and does not cause contamination.

The BWM Convention applies to all ships carrying ballast water, except warships and vessels operating only in domestic waters. All ships of 400 gross tons and above are required to have an approved Ballast Water Management Plan and to be issued with a certificate of compliance.

Compliant ships must release less than 10 cells/m3 of organisms larger than 50 μm such as plankton, and less than 250 colony forming units (cfu) per 100 ml of bacteria such as Escherichia Coli, reduced to 1 cfu/100 ml in the case of toxigenic Vibrio cholera.

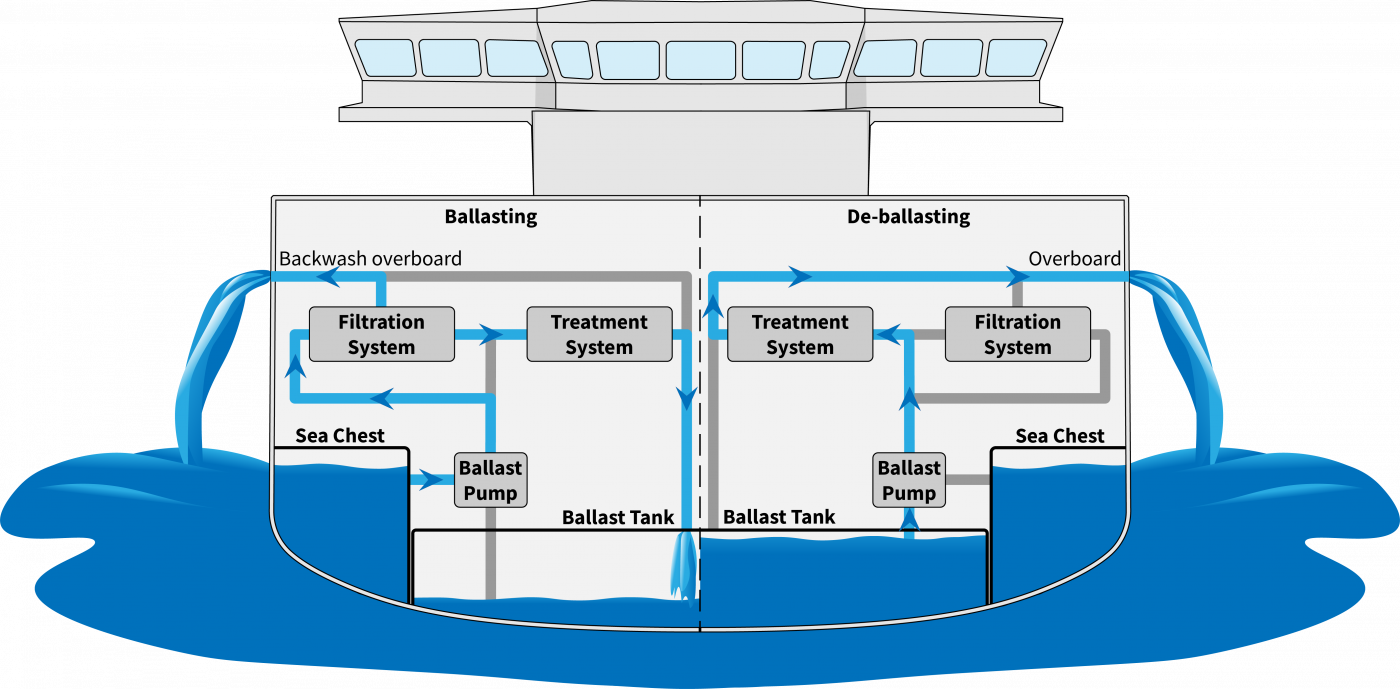

The systems used to treat ballast water are designed to separate the water from solid particles and disinfect it. The solid-liquid separation is (generally) a mechanical process carried out during ballasting, through filtration or hydrocyclone equipment. The waste stream containing the suspended solid particles can be safely discharged in the same place where the ballast water was taken in.

Disinfection of ballast water prior to its release can be achieved via physical or chemical processes. Physical processes include water deoxygenation to asphyxiate the microorganisms, or UV irradiation to deactivate their vital functions. Ballast water can be treated chemically with biocides, in which case the impact and management of the relative by-products have to be approved as part of the BWM Plan. Chemicals can be stored on board the ship, which can pose a risk on its own and will require appropriate mitigation. Treatment systems differ from ship to ship, based on type, ballast capacity, available space onboard, operating profile, and other technical requirements.

Ballast management remains a cornerstone of our modern maritime fleets, ensuring enhanced manoeuvrability, reduced structural stress, and mitigated risk of accidents. It's an indispensable tool for safe and efficient maritime transportation, and good practices ensure confidence in the industry's commitment to safety and the environment.

For more information on ballast water management, see lr.org/bwm.