Maritime Innovation In Miniature

Océan

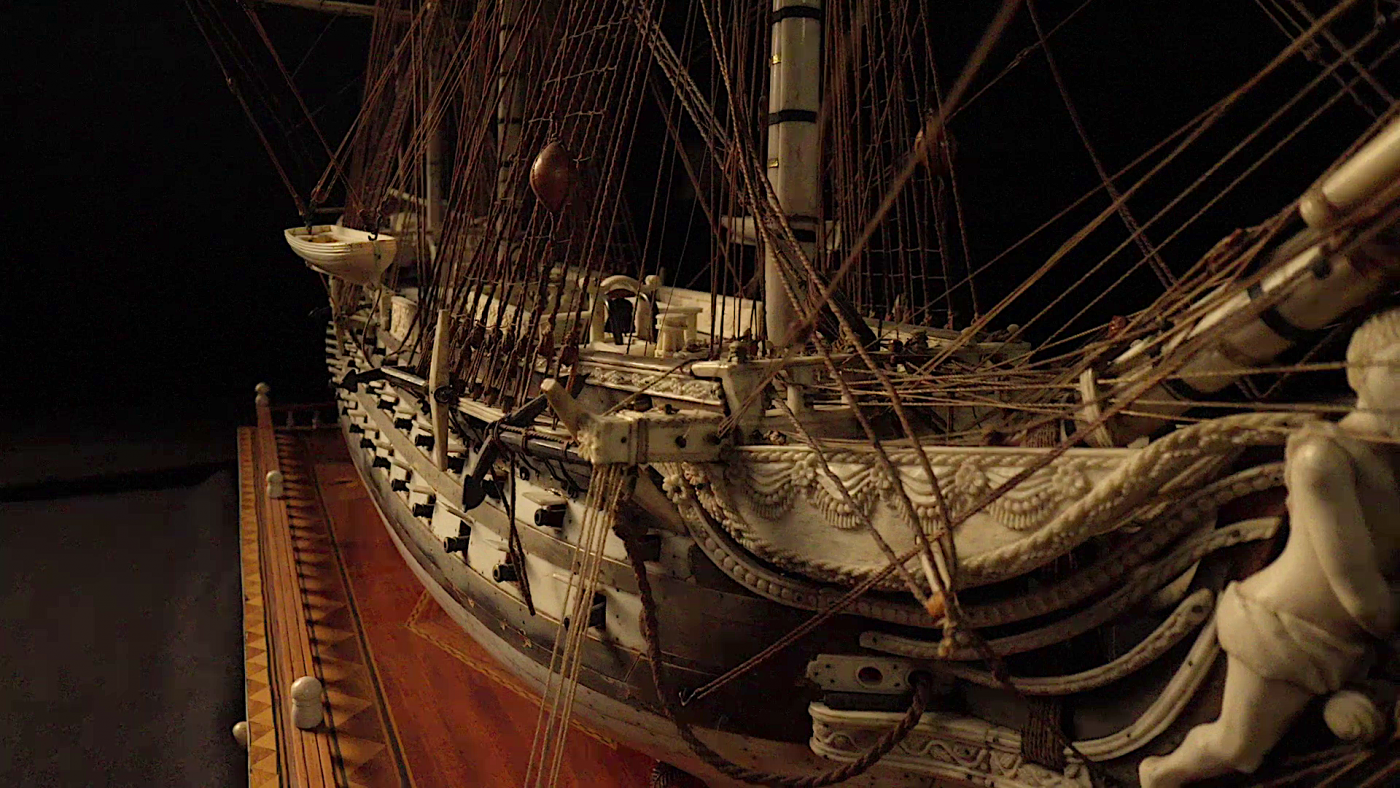

This is a model of the French battleship Océan, launched at Brest on 8 November 1790. Ships of the Océan class were designed to be flagships of the French navy and were the largest in the world. Océan was armed with 120 guns, had 3,250 square metres of sails, a crew of 1,130 and displaced 5,095 metric tonnes – that’s 1539 tons MORE than Nelson’s HMS Victory. In this period the French led the world in building large fighting ships.

The French navy was divided into five ranks and these ships were of the ‘Premier Rang’. The equivalent of the British ‘First Rate’. Eighteen ships were built in this class, to a design by the innovative French marine engineer Jacques-Noel Sané who standardised the designs of French ships of the line.

The model was made by a French prisoner of war. Prisoners were encouraged to make items to sell at daily markets and ship models were relatively common. This example, however, is a masterpiece, the finest prisoner of war ship model to have survived. They were made of bone, ivory, or tortoiseshell, in sizes from two inches to six feet or more. Whalebone was used for larger models but most, like the Océan, used ordinary beef bones saved from the prisoners’ meals. The rigging was made of hair, cotton or thread, made exactly as real rope. They were produced by teams of craftsmen, each contributing specific parts such as figureheads, rigging, or guns, and were realistic but not literally exact.

The Océan class of ships were significantly longer than any previous warship - stretched by 10 feet to carry their extra guns. The largest guns, found on the lower deck, were 36 pounders – far heavier than the British 32 pounders. Each gun was so powerful and heavy it required a crew of fourteen to operate and manoeuvre, while a British 32 pounder needed only seven. Her guns were iron, cast as a solid and bored out; the guns of the model are wood, either turned on a lathe or made with files. The model shows the guns partly run out, ready for action.

The Océan class had gunports just 6ft 10in above the water amidships but this was still higher than comparable British ships: the Queen Charlotte had ports only 4ft 6in above the sea and at the battle of the First of June the lower deck was full of water. Océan would also have carried six 36pdr obusiers on the quarterdeck and forecastle – a devastatingly powerful gun that fired explosive shells at low velocity, to be used against personnel.

The Océan class were built with less sheer - the curve down from forecastle to waist and up to the quarterdeck - than comparable British ships. And also less tumblehome – the angle between the hull at its widest and narrowest points. Although these features are not represented on this model with great accuracy, her shape still speaks of design choices that favoured speed over stability in heavy seas.

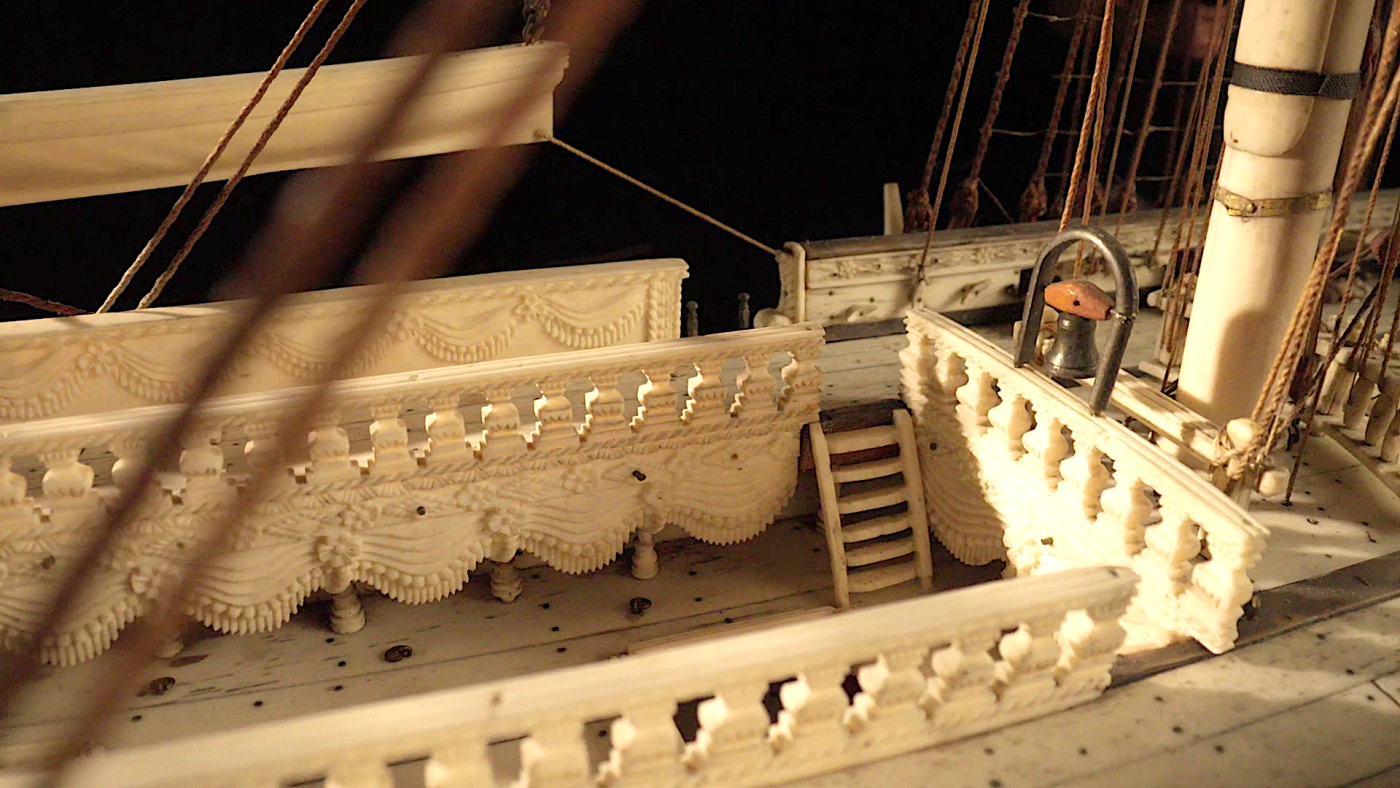

The model’s stern has the classic horseshoe shape associated with Sané, but the modeller has added details to add value and show off his skill: there are no fewer than sixteen carved figures including two sirens and four mermaids, two of them playing conches. The model has open galleries, perhaps again to show the maker’s skill in carving the pillars, the balustrades with twisted rope patterns, and the Sea God’s trident; but the ship itself had closed galleries, which enlarged the officers’ cabins and supported the decks above.

The figurehead is also decorative not accurate. The model shows the planking below the waterline: it is perfectly fitted by the modeller, tapering up to the transom and widening to fit the rudder post, but it is not coppered. From 1786, all new French ships were meant to have copper sheathing, which prevented the ship worm Teredo navalis and inhibited weed and barnacle growth.

The black-and-white colour scheme is probably fanciful: a scale model of an Océan-class ship at the Swiss Museum of Transport in Lucerne shows the sides yellow and the gunport lids red a contemporary coloured etching of another ship in her class shows the upper and middle decks yellow and the lower deck grey.

Launched in the immediate aftermath of the outbreak of the French Revolution, Océan soon found herself thick in the action. At the Glorious First of June in 1794, fought at the height of the Reign of Terror, she engaged the British First Rate Royal Sovereign. She was hit with around 250 cannon balls and took 300 casualties - but was not captured. A year later She was in action again at the Battle of Groix, and in 1809 at Basque Roads, where she was set ablaze by a British fireship, was grounded, and beat off British attacks for four days.

She subsequently had a long life and was not broken up until 1856. But when she was taken apart, 201 cannon balls from 1794 were found in her hull, the true embodiment of French seapower from the great age of sail.