Today commercial seafaring remains a dangerous professions, with 2,000 lives lost every year. From 1834 our ship plan and survey report collection consists of survey reports, certificates, photographs, and correspondence charting the lives of small and great vessels, from construction to demise.

From 1890, Lloyd’s Register started publishing annual (and then quarterly) Casualty Returns relating to losses of vessels worldwide within incremental periods. Prior to this, surveyors often reported to government commissions on shipwrecks and unseaworthy vessels for decades. Information on losses at sea have long been gathered in Lloyd’s Register’s work.

In operation from c.1890, wreck reports recorded details of a ship’s loss, acting in much the same way as a death certificate. Written by a Lloyd’s Register surveyor, sent to the Classing Committee, and filed with the rest of a ship’s documentation, that vessel’s entry in the Register of Ships was finally expunged.

Digitising these 1.25 million records for our online catalogue, thousands of, often tragic, sometimes amusing, and frequently bizarre stories behind these wrecks are emerging.

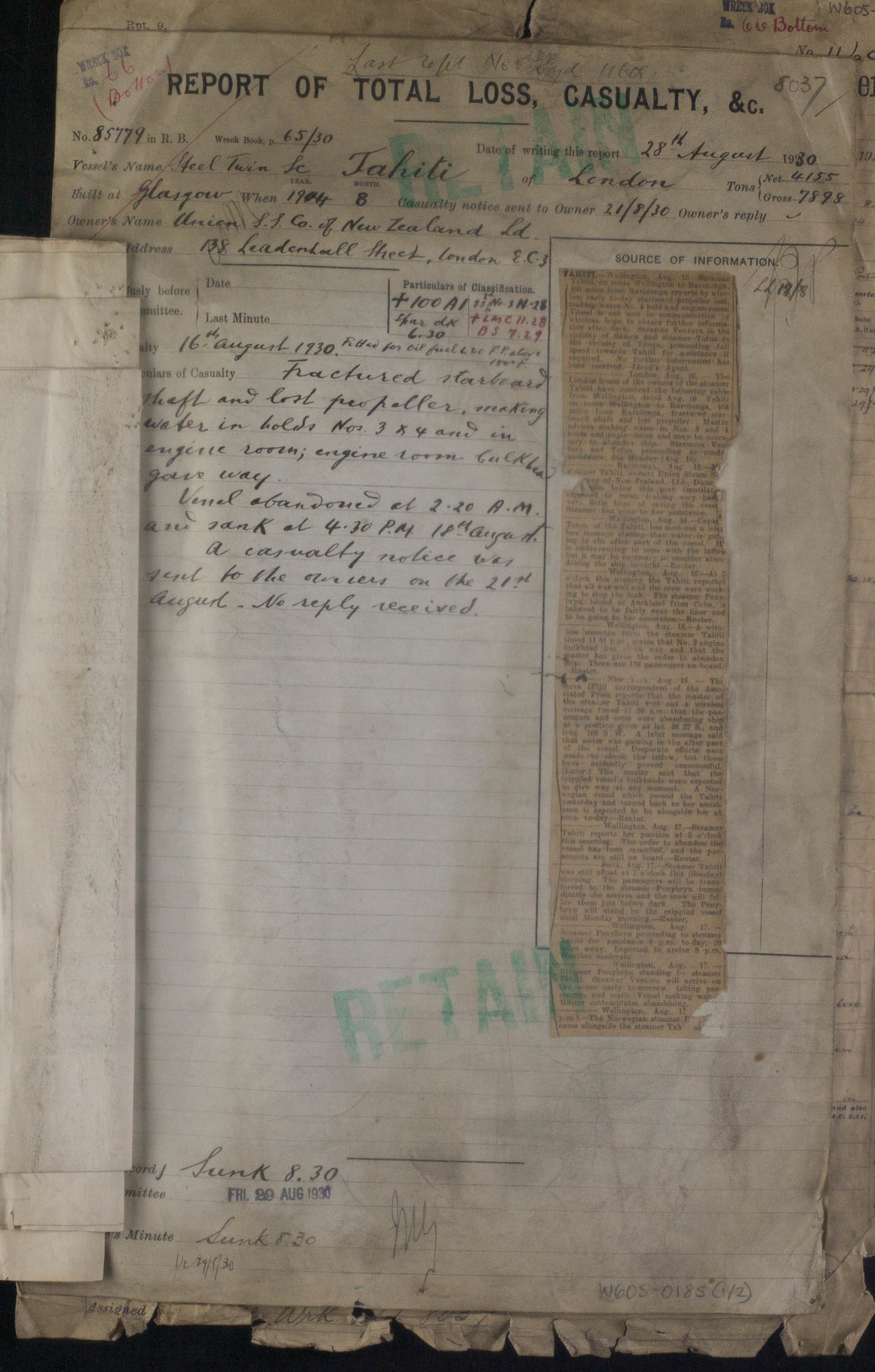

RMS Tahiti

Built in 1904, on the River Clyde, the RMS Tahiti (ex. Port Kingston) measured over 7,500 tons, intended to carry passengers for the Union Steam Ship Co of New Zealand. Voyaging from Wellington to San Francisco, Tahiti was carrying around 250 people on board, including crew, before breaking down around 500 miles South of Rarotonga on 15th August 1930. It was discovered on inspection that her propeller had gashed huge holes in her hull.

Radioing for help, the crew anchored the ship and worked round the clock for three days bailing and pumping water out of Tahiti. Stuck in the middle of the South Pacific the passengers on board patiently waited for news.

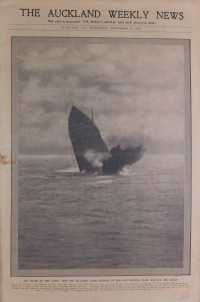

After three days of waiting, another ship, the Ventura, arrived on the morning of the 18th August. All passengers were loaded into the lifeboats at midday, but just as the mail was being loaded, the crew declared she was too low in the water and abandoned ship. At 4:30pm Tahiti took her final plunge and sank stern first.

Within our archive this complete edition of the Auckland Weekly News tells the story of the ‘Death of the Tahiti’, as experienced by her passengers!

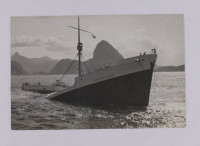

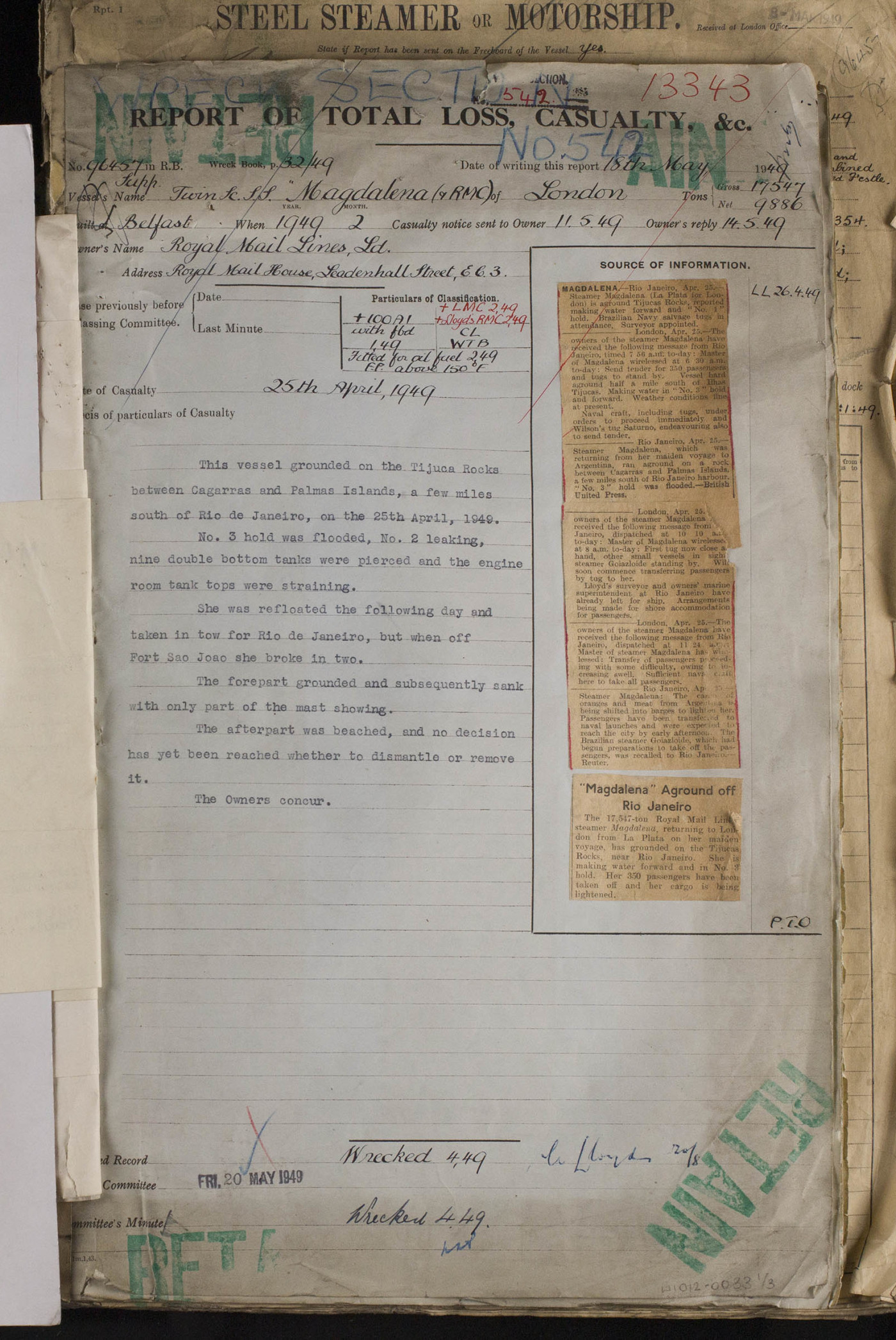

RMS Magdalena

The Magdalena was a refrigerated passenger liner, built in 1948 by Harland & Wolff, their first constructed after the end of the Second World War. Measuring 17,547 gross tons and 570 feet in length, she was the third largest ship being constructed in the United Kingdom at that time.

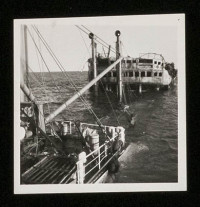

Intended for service between the UK and South America, Magdalena was wrecked off Brazil on her maiden voyage carrying 237 crew and 347 passengers. Striking the Tijucas Rocks, she was grounded at 04:40. Following an SOS, all lives were safely rescued, before she finally sank and broke up on 30th April.

Despite being declared a total loss, one newspaper optimistically included that many ‘bottles of beer remained unbroken.’ Her loss gained notoriety; her insurance payout (£2,295,000) became the largest for any marine casualty in British history.

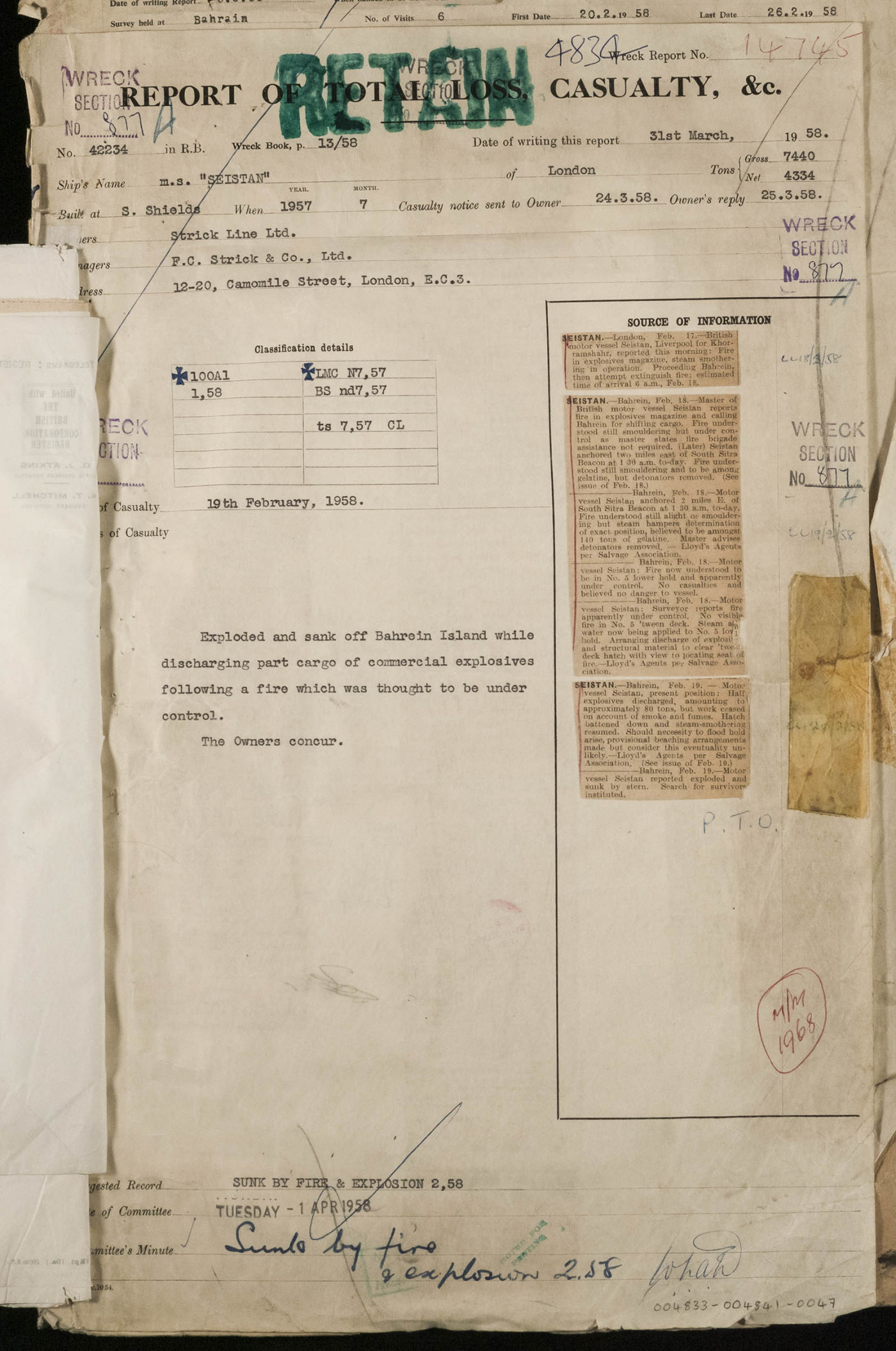

MS Seistan

Completed July 1957 at South Shields for the Strick Line Ltd, Seistan was a single screw motor ship, measuring 450 feet in length, and 7,440 gross tons, intended for the Persian Gulf trade.

Leaving London on 27th January, bound for Khorramshahr, Seistan was carrying over 175 tons of commercial explosives. Conveying 66 members of crew, her owners reported a fire in Seistan’s no. 5 hold through their agents, Gray McKenzie & Co Ltd. She was to proceed to Bahrain Island for an interim certificate following an inspection of her hold by Lloyd’s Register surveyor.

The hatch to the hold was battened down and suppressing steam was released, both of which were expected to smother the flames, and roughly half her cargo was discharged.

At 21:35 hours, 19th February, the Seistan suffered a violent explosion. The force of the blast would leave only 19 survivors, throw flames 300 feet into the air, and sink the tug Sohail moored alongside Seistan.

Sinking stern up to the end of the superstructure, Seistan lay in 42 feet of water, sinking completely on 24th February. The newspapers cuttings, correspondence, and photographs from our archive tell the story of her fire, explosion and destruction.

As we digitise our archive collection’s for open access, the stories and details of wrecks worldwide are becoming available for research and understanding. Whilst these wrecks continue to lie on the floors of our oceans, seas, and rivers, their records will be brought to the surface. How we put these records to best use is up to us.