This article was written for the Rewriting Women into Maritime inititative by Sarah Robinson, Senior Journalist at Nautilus International.

Introduction to Officer pioneers of the 1970s, contributed by Nautilus International

When we think of women in the 1970s workplace, we might envisage put-upon secretaries with lecherous male bosses, or female factory workers whose skills with a sewing machine were less valued than those of a male welder.

Yet, for the first time in history, employment law was starting to be on women's side. In the UK, the Equal Pay Act 1970 had prohibited any less favourable treatment between men and women in terms of pay and conditions of employment.

So even in the notoriously traditional Merchant Navy, we started to see young women choosing to train as deck, engineer and radio officers – attending nautical colleges alongside young men, getting jobs at sea on the same terms as their male counterparts, and joining the same maritime trade unions.

The union known today as Nautilus International is the result of several mergers of maritime unions in the UK, Netherlands and Switzerland over 150 years. In 1970s Britain, ships' officers would have joined one of two Nautilus predecessor unions: the MNAOA (Merchant Navy and Airline Officers' Association) or the REOU (Radio and Electronic Officers' Union).

Nautilus here celebrates the 1970s gender diversification of these unions by telling the stories of three officers who stood out from the crowd.

Marion Pettigrew

Engineer Officer

It is 1973 in Motherwell, Scotland, and a girl called Marion Pettigrew is looking at subject options for her ‘O’ level exams. She decides to tick a box to study technical drawing and metalwork rather than domestic science – the first girl at her school to do so.

Her spirited choice leads her to get to know the metalwork teachers, who hear how much she wants to travel. Mr Hunter has a relative in the Merchant Navy, so suggests that Marion gives this a try. It was the spark of a career which still stands out as unusual for a woman 50 years later.

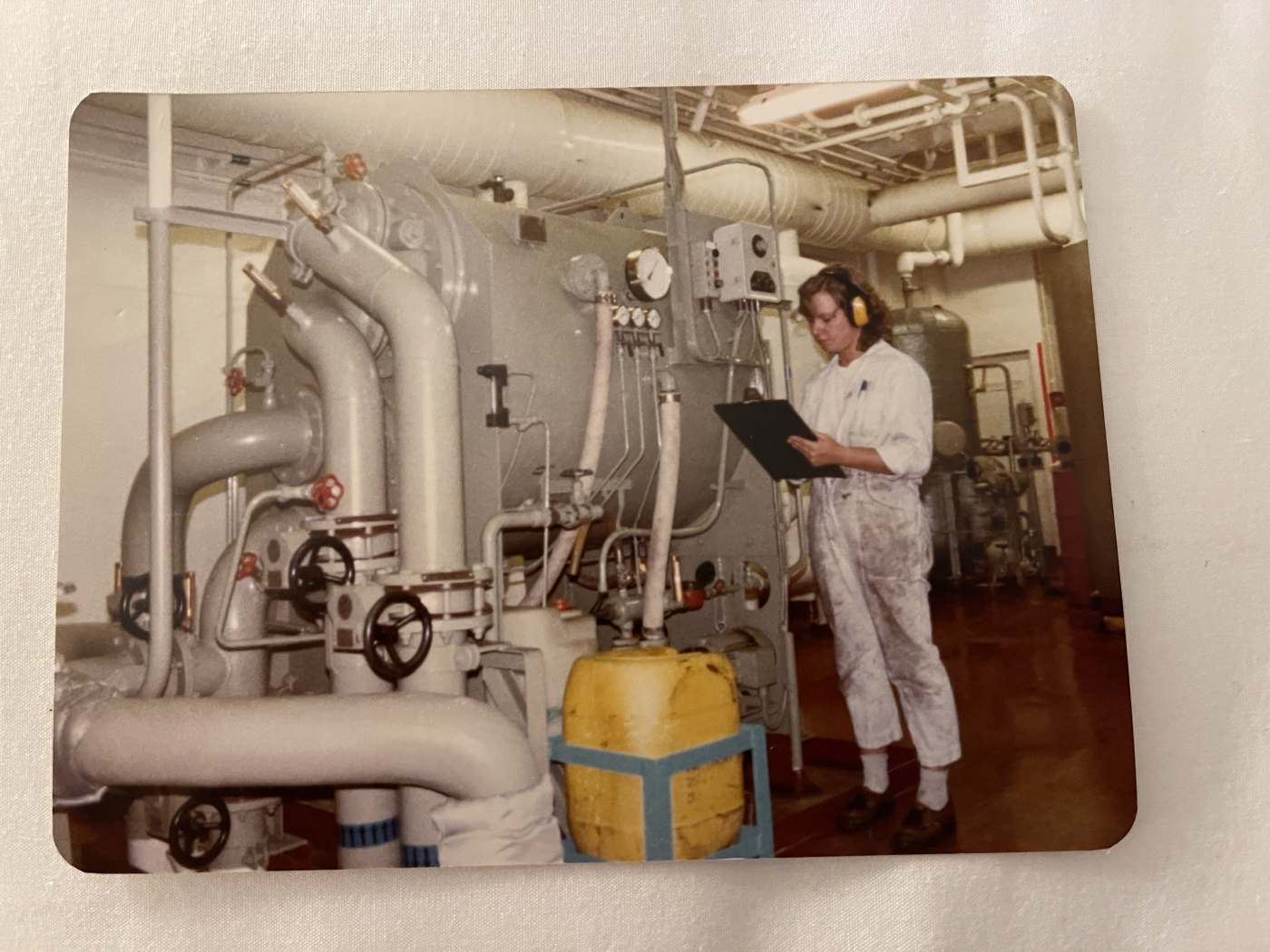

1970s engineer officer Marion Pettigrew, still finding the fit of her boiler suits a challenge after they had been through the wash © Courtesy of Marion Sambridge

Applications and interviews

Sending out 22 enquiry letters about Merchant Navy engineering cadetships in 1975, Marion had a feeling shipping companies wouldn't consider her if she gave her first name, 'so I just wrote my initial M. Sure enough, all the replies came back addressed to Mr Pettigrew! But I ended up with three interviews.'

For the first interview, at Ben Line, Marion was told to bring her father. 'The guy berated him for allowing me to consider this as a career, and went on and on about whether I'd be able to swing a 50lb hammer.'

The second interview was no better, however at P&O's cargo division, everything was different. 'They gave me a proper interview like everyone else, which included modern techniques like psychometric tests.'

And so it was that Marion, aged 17, started her P&O engineer officer cadetship in September 1976 at Glasgow College of Nautical Studies.

Mixed experiences at college

The training for engineering cadets was a four-year course, with two college years, a year at sea and then back to college. Cadets were encouraged to join the Merchant Navy and Aviation Officers' Association (MNAOA) – a predecessor trade union of Nautilus International.

Marion was the only female engineer cadet out of 107 in her college year, and it wasn't easy at first. 'There were all these snotty young boys, the majority saying, "what are you doing here?". Thankfully, around November, some deck cadets came back from their sea phase, including one female who became a lifelong friend. With new friends who accepted me, I settled in and my studies improved.'

Stepping aboard in size 4 boots

When the time came for Marion's sea phase, she flew out to Saudi Arabia to join the P&O gas carrier Garinda after a big effort to get equipped. 'It had been hard to find steel toe-capped boots in size 4 and my mum had needed to adjust my boiler suits to make them fit.'

Her presence onboard ship was not only a new experience for Marion, but also for P&O, for whom she was the first ever female engineer. Her shipmates weren't too sure what to make of her, but she remembers them as friendly and helpful.

Her other two vessel placements – on general cargo and container ships – also generally went well, and she decided to take a job with Overseas Containers Ltd (OCL) when she finished her cadetship.

A good company to work for

Marion served on container ships with OCL – later known as P&OCL – for the rest of her sea career. 'OCL was a decent company with modern ships and a good atmosphere onboard,' she explains. 'They made an effort to keep crew members together who knew each other, which made it easier to just get on with the job rather than people being surprised to see me.

'I only had one difficult chief engineer, who used to sing a nasty little song about me. Also, there was a captain who told OCL he didn't want a woman engineer onboard, but the company backed me, and he ended up sorting himself out.'

Translating sea experience into shore success

In September 1985, Marion decided to come ashore. Remaining with P&OCL, she took an office job selling second-hand containers, and her next move was to Tiphook Container Rental, where she set up an engineering department relating to container repairs. She also worked in Tiphook's IT department as a user acceptance tester.

In 1992, Marion finally left maritime to establish herself as an independent software developer and business analyst – work that she still does.

Reflecting on the past

Now known as Marion Sambridge, and with a grown-up daughter, she looks back at her youth with a certain bemusement at her own boldness.

'It's strange to think of myself as a pioneer,' she muses, 'because I didn't set out to do that; I was just very bloody-minded when it seemed like I might not be allowed to do something!'

Marion remembers her time at sea vividly. 'At its worst, it could be dirty, sweaty and lonely – and frightening in bad weather. There were a few difficult people, but I gave as good as I got and never felt unsafe.

'At the good times, it was the best time of my life. I went to amazing places, did interesting work and met the best people, many of whom are still good friends. I owe my career to the people at P&O and OCL and I am forever grateful to them.'

Back to the exhibition home page.