For as long as humans have utilised fire, we have always needed rules to prevent it going out of control. In the developed world, every aspect of society, from our homes to our jobs to public places, are built with fire safety in mind. The same is true of ships. However, they have their own challenges. Ships are enormous, often isolated from help, have few methods of escape, and carry their own fuel along with many systems whose malfunction could start a fire. All of these factors make fire safety both a challenge and a priority. Any failure can cost lives; there have been plenty of fires on board ships which have vividly demonstrated that.

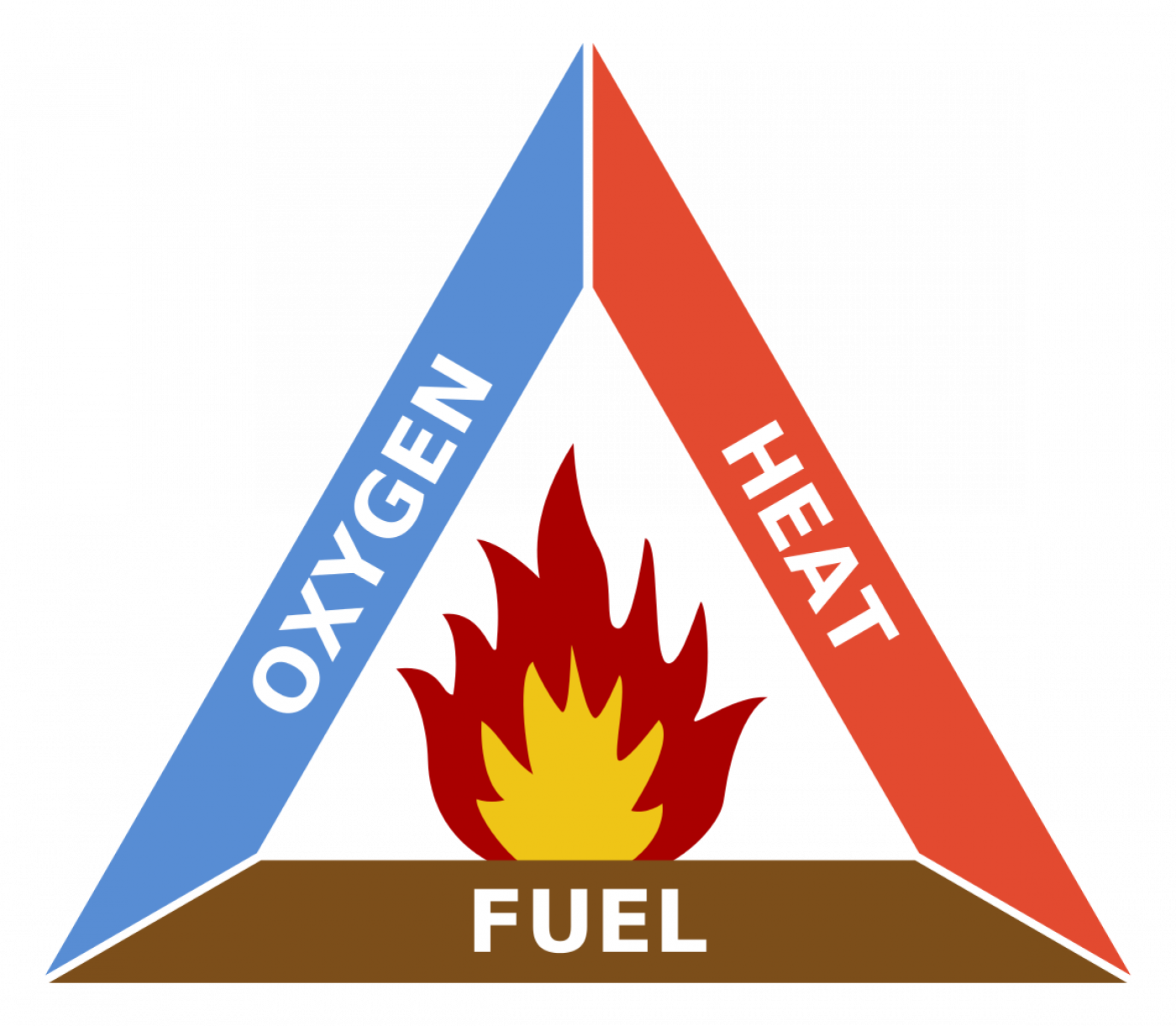

The fire triangle, used to illustrate the relationship between heat, fuel and oxygen. Image licensed under Creative Commons.

No matter where a fire is, it needs three things to start: heat, fuel, and oxygen 1. Fire safety is about either preventing these three things from mixing, or removing one of these to suppress the fire. Historically, this was a challenge on ships. Many early sailing vessels were made of wood: an excellent fuel source. New dangers came from the invention of the steam engine, a device which relied on fire to move the ship. At the same time, ships became more accessible to the general public, with more and more people using larger and larger ships to cross long distances between countries. It was a recipe for disaster, and unfortunately, it usually takes a disaster before action is taken.

The precipitating event that brought fire safety on board ships into the spotlight was the fire on board SS Moro Castle. A fire of unknown origin, fanned by stormy winds, swept through this luxurious ocean liner in 1934, leading to a loss of 137 people, almost a quarter of those onboard. The tragedy was made worse by the ship’s varnished wooden interior and the crew’s incompetence. They were completely untrained for such an incident, which made any safety features like lifeboats or hoses unworkable 2. The fire was the catalyst for the 1948 Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) convention to mandate more fire safety requirements for passenger and cargo ships. The 1974 SOLAS convention- which is still in force today- revised these in response to passenger ship fires in the 1960s- Dara and Meteor, requiring that all passenger ships are made of non-combustible materials and have sprinklers or other fire suppression systems. Further amendments were made after the 1980 fire aboard the Scandinavian Star that killed 160 people, then revised again in 1996 and 2000. As well as the SOLAS Convention, there now also exists an International Fire Safety Systems (FSS) Code 3. Each regulation tries to tighten the rules to account for all possibilities, to ensure fewer disasters like Morro Castle or Scandinavian Star take lives.

The SS Moro Castle of the Ward Line, seen before her fatal fire. Image taken from public domain.

So, what are the current regulations like? It depends on the type of ship. Passenger ships, including ferries, as well as tankers have tighter regulations; the former due to the potential for loss of life, the latter for the flammability of their cargo. In general, however, fire safety on ships can be broken down into three categories: fire prevention, fire detection, and extinguishing any fires that arise. If all else fails, a provision is made for escape. Provision requirements for training are also listed. All these are listed in Chapter II-2 of SOLAS 4. Most countries have implemented these regulations in legislation for vessels under their flag.

For fire prevention, it is important to firstly, talk about building materials. Passenger ships are required to be made of steel, especially around the engine, and have all materials of passenger quarters and working areas of the ship be fire retardant 5. Tankers must have methods for venting any flammable gases 6. Once launched, there are two main areas most ships focus on: their engine and their electrics. In the engine and its surroundings, proper maintenance is essential to prevent fuel or oil leaks, as well as insulation for hot surfaces, to prevent any leaks from catching fire. Maintenance of electrical systems is also vital, as well as not overloading the systems of a ship with a crew’s devices, such as kettles 7. Crew training is important, as their good practices, such as not smoking in hazardous areas, storing hazardous chemicals safely, and sticking to best code of conduct and maintenance, is what makes this work. Regular refreshers of training and inspections should ensure all is well on board the ship and in the minds of its crew.

Now onto fire detection. This does not vary much by vessel, or from a regular home: the smoke detector is always king. Unlike homes, these are often connected via sensors to the ship’s systems, alerting the bridge, alongside flame or heat detectors. But, once again, training is vital. Teaching crews what to look for and regular patrols enables them to quickly detect any fires and respond to it.

Foam fire suppression systems being tested on the aircraft carrier USS Kittyhawk. Image provided by the US Navy.

Finally, fire fighting. Much like with smoke detectors, the familiar fire extinguisher is the go-to for all vessels great and small. Larger ships will also often have fire hydrants or pumps, while those larger still, such as passenger vessels, will have sprinklers or other fire suppression systems. High-expansion foam, a method of smothering the fire using liquid foam, is best for engine rooms. Bulkheads often come down to localise fires. Inert gas systems are best for tankers to completely deprive any fire of oxygen 8. For all of these, crew must know how to use them properly. If all else fails, crew must be taught how to evacuate themselves and passengers properly, though if the above three points have been properly followed, there will hopefully be no need for that. Emergency response has to be instinctive. For that, drills are essential.

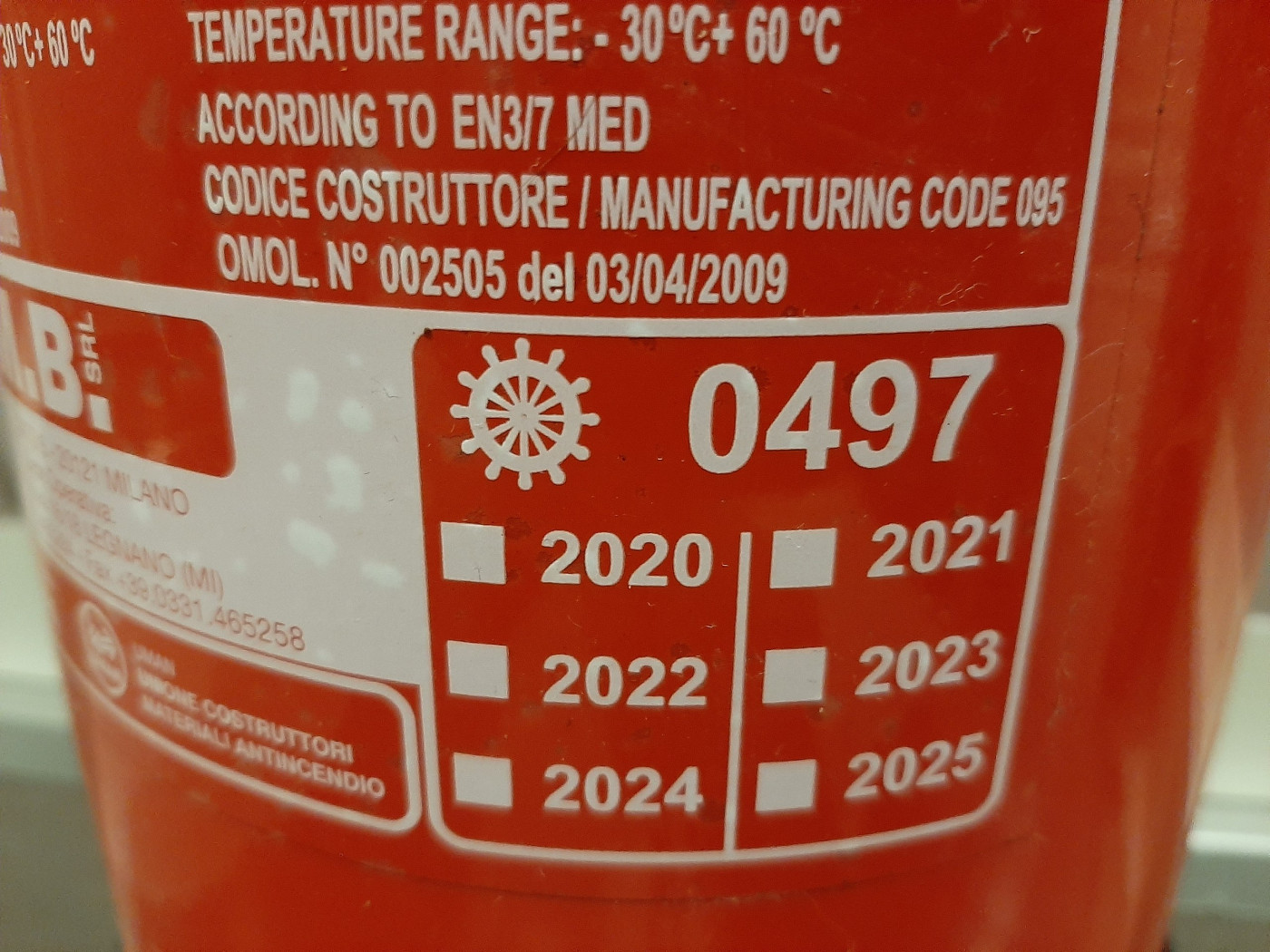

A fire extinguisher on board a ferry carrying the wheel accreditation mark, which means it conforms to standards set by the Marine Equipment Directive (MED), a set of regulations valid across the whole EU. Image licensed under Creative Commons.

Fire safety is just as critical for smaller vessels, such as pleasure boats and fishing vessels. There is less storage for safety systems, and should a fire break out on a small craft, there are fewer escape options for the occupants. Many of the principles of fire prevention discussed above, such as good building materials and insulation, applies here. It is only fire detection and fire fighting equipment that depends on size. For example, according to UK guidelines, a fishing vessel of less than 7 metres only needs a fire blanket and fire extinguisher, but a vessel above 12 metres but below requires two fire extinguishers, plus fire pump and hose 9. All of these, it must be noted, are manually operated. Many smaller vessels also do not have sophisticated automated systems that alert crew, or trigger fire fighting measures. Smoke detectors and gas leak indicators are recommended 10. This limited equipment means crew training here is more vital than ever, in both preventing, spotting, and tackling the fire.

New hazardous cargos, like electric cars and lithium batteries transported in containers pose continued challenges, “The risk of a container fire occurring is thought to be on the rise, with 64 ships lost to cargo fire in the past 5 years alone. Cargo fires on container vessels can cause major damage to the ship itself, damage and loss of goods and put the crew’s lives at risk.” The IMO developed the International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) code to help businesses worldwide transport dangerous goods safely over the oceans. Safetytech Accelerator are focusing on innovative solutions to combat the increasing threat of cargo fires in container shipping.

As has been demonstrated, fire safety on ships is both a highly multifaceted concept, and yet, very simple. There are many nuances which could not be covered, but most things come down to a synergy between equipment and crew training. The human element is the lynchpin: no fire safety method is useful if nobody knows what to do. All these rules hopefully mean incidents like Morro Castle are a thing of the past. But transportation of hazardous cargos continues to pose a problem. Yet, much of what is presented here is, it must be remembered, only theoretical. It is up to the owners, the crews, and in some cases, passengers, to help make their sea journey the safest it can be. Fire is a destructive force. Let’s keep it contained.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Lloyd’s Register Group or Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

A master's guide to Fire Safety on Ferries

Lloyd's Register - Summary of SOLAS Requirements for Maintenance, Servicing, Testing and Drills

Lloyd's Register - Guidance Notes for Fire Loading and Protection

Lloyd's Register Foundation - Engineering Fire Safety in South Africa

People and Places, and Lloyds Register Foundation - FEEFA; Fire Safety Engineering Where It's Needed Most/ South Africa

Lloyd's Register Foundation HEC - Hindsight Perspectives: Fire at Sea

Lloyd's Register Foundation HEC - The Cospatrick Disaster

Lloyd's Register Foundation HEC - Guano: The Perilous Cargo of Flammable and Noxious Fertiliser

Lloyd's Register Foundation HEC - 'What Harm Could One Do?': The Disastrous Result of Smoking at Sea

Footnotes

-

1

“Introduction to Fire Safety.” HSE, www.hse.gov.uk/fireandexplosion/fire-safety.htm. Accessed 13 Apr. 2024.

-

2

Hicks, Brian. When the Dancing Stopped the Real Story of the Morro Castle Disaster and Its Deadly Wake. Free Press, New York, 2006.

-

3

“History of Solas Fire Protection Requirements.” International Maritime Organization, www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Pages/History-of-fire-protection-requirements.aspx. Accessed 13 Apr. 2024.

-

4

“Summary of Solas Chapter II-2.” International Maritime Organization, www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Pages/summaryofsolaschapterii-2-default.aspx. Accessed 14 Apr. 2024.

-

5

The Merchant Shipping (Fire Protection: Small Ships) Regulations 1998, Part IV- Passenger Ships https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1998/1011/part/VI/crossheading/passenger-ships-1/made Accessed 14 Apr. 2024

-

6

The Merchant Shipping (Fire Protection: Small Ships) Regulations 1998, Part IV- Tankers of Class VII (T) https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1998/1011/part/IV/crossheading/tankers-of-class-viit/made Accessed 14 Apr. 2024

-

7

Ross, Mark. “Fire Prevention on Board Ships.” Shipowners, Shipowner’s Club 15 May 2017, www.shipownersclub.com/latest-updates/news/fire-prevention-board-ships/. Accessed 14 Apr. 2024

-

8

Mohit. “16 Fire Fighting Appliances and Preventive Measures Onboard Ships.” Marine Insight, 1st June 2021, www.marineinsight.com/marine-safety/16-fire-fighting-appliances-and-preventive-measures-present-onboard-ship/. Accessed 14 Apr. 2024

-

9

Marine Management Organisation, “Guidance: Annex 1 MCA Code of practice for small fishing vessels mandatory items”, 23rd February 2024, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/fisheries-and-seafood-scheme-guidance/annex-1-mca-code-of-practice-for-small-fishing-vessels-mandatory-items, Accessed 14 Apr. 2024

-

10

“Fire Safety on Boats”, Home Office, November 2021, vol. 4. Accessed via PDF.