Coal has always been a filthy, dusty and dangerous cargo, making ships unstable if not properly distributed (trimmed). Liable to shift in heavy weather, it also choked pumps and was (and still is) liable to spontaneous combustion. Many ships and lives were lost while carrying coal, especially in the heyday of steam power when the demand for coal was enormous. Coal dust was a health hazard that affected all those involved in the loading, trimming and unloading of coal cargoes, as well as in the refuelling (bunkering) of steamships. Especially gruelling was the work of the black gang – the firemen and trimmers who kept the boilers running in steamships.

Timber, charcoal and peat provided the earliest fuel for fires, though from antiquity coal was also exploited wherever it was easily obtained from surface deposits, the sides of valleys or cliffs, or washed up on beaches. Coal is a combustible sedimentary rock, brownish-black or black in colour and occurring as layers or seams. Over millions of years decaying trees and plants in vast tropical forests and swamps formed peat deposits and eventually coal. The different types or ranks of coal are classified by their carbon content and heating value. The highest quality is anthracite, a smokeless coal also known as black coal or hard coal and composed almost entirely of carbon. Bituminous coal (containing bitumen) is the most abundant, with numerous varieties including house coals (suitable for domestic fires), coking coals, gas coals and steam coals. Coking coals are ideal for converting into coke, an almost smokeless fuel that replaced charcoal in the iron and steel industry. Gas coals were used for manufacturing coal gas for lighting and heating in towns, producing valuable by-products like coke and coal tar. Steam coals (or thermal coals) were ideal for steam engines, and some were classed as semi-bituminous or anthracite. Because the deposits from South Wales were preferred for Royal Navy steamships, the name Admiralty coals was also common. The lowest grade or rank of coal is lignite (brown coal). 1

Heaps of coal

Delivery of ‘house coal’ in sacks

Heaps of coal

Delivery of ‘house coal’ in sacks

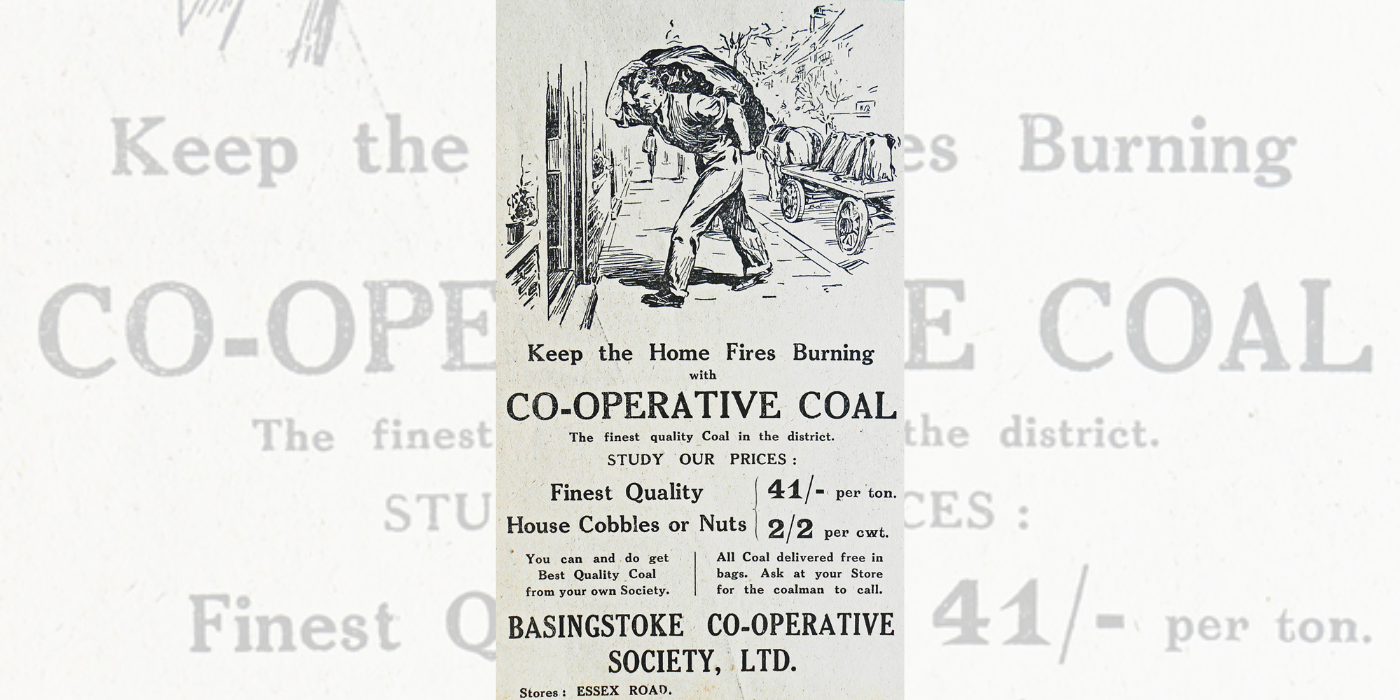

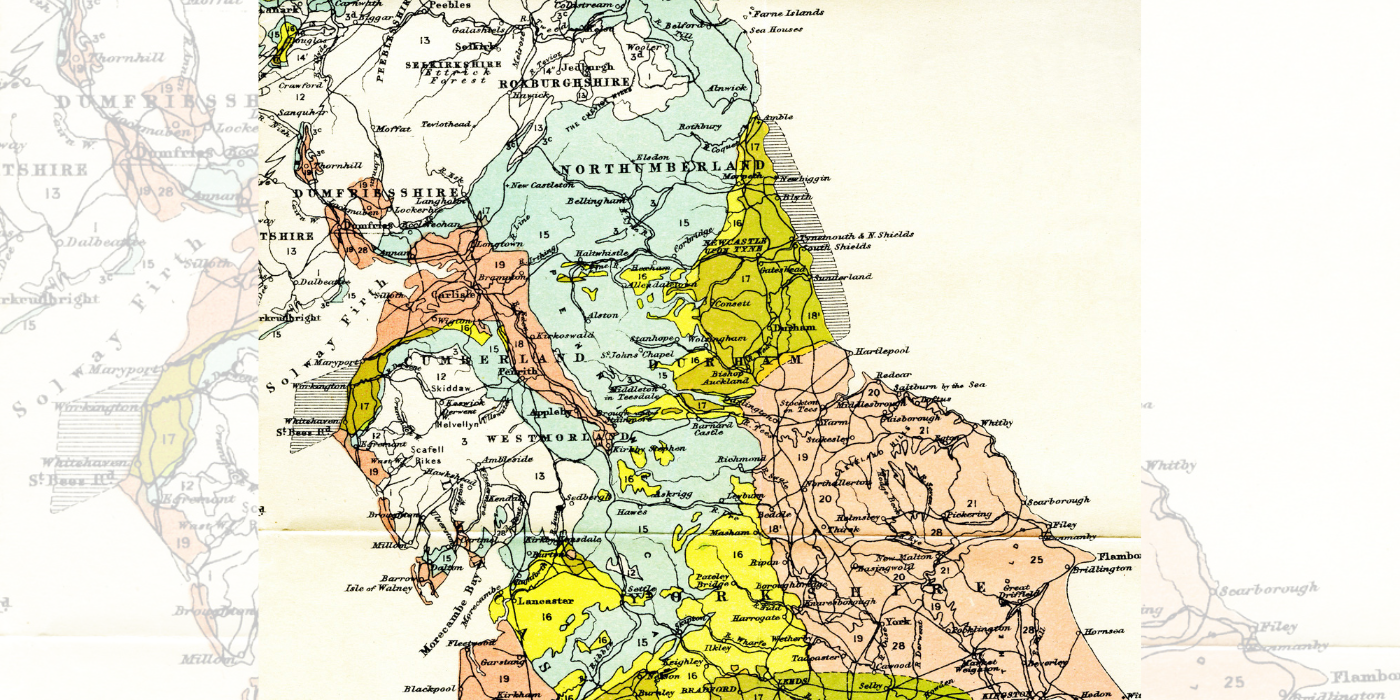

The need for coal grew significantly with the invention of the steam engine, and from the early 18th century this steam power was able to pump water from deep mine shafts. Britain became the world’s leading producer of coal and was transformed into an industrialised nation by steam engines that powered all kinds of industries, as well as railway locomotives and steamships. Until the formation of a railway network, it was not profitable to move coal any distance overland, but coal close to the coast was conveyed by sea, so that from medieval times the term ‘sea coal’ was used for coal. By 1700 coastal vessels were taking considerable amounts from mines in north-east England to London and beyond. As other coalfields were developed, many more ships carried coal to countless ports around the British Isles. It was also commonplace to beach small vessels and discharge their cargo into carts, while canals and rivers took coal inland. 2

Coalfield of north-east England

Polluting steamers on the River Clyde

Coalfield of north-east England

Polluting steamers on the River Clyde

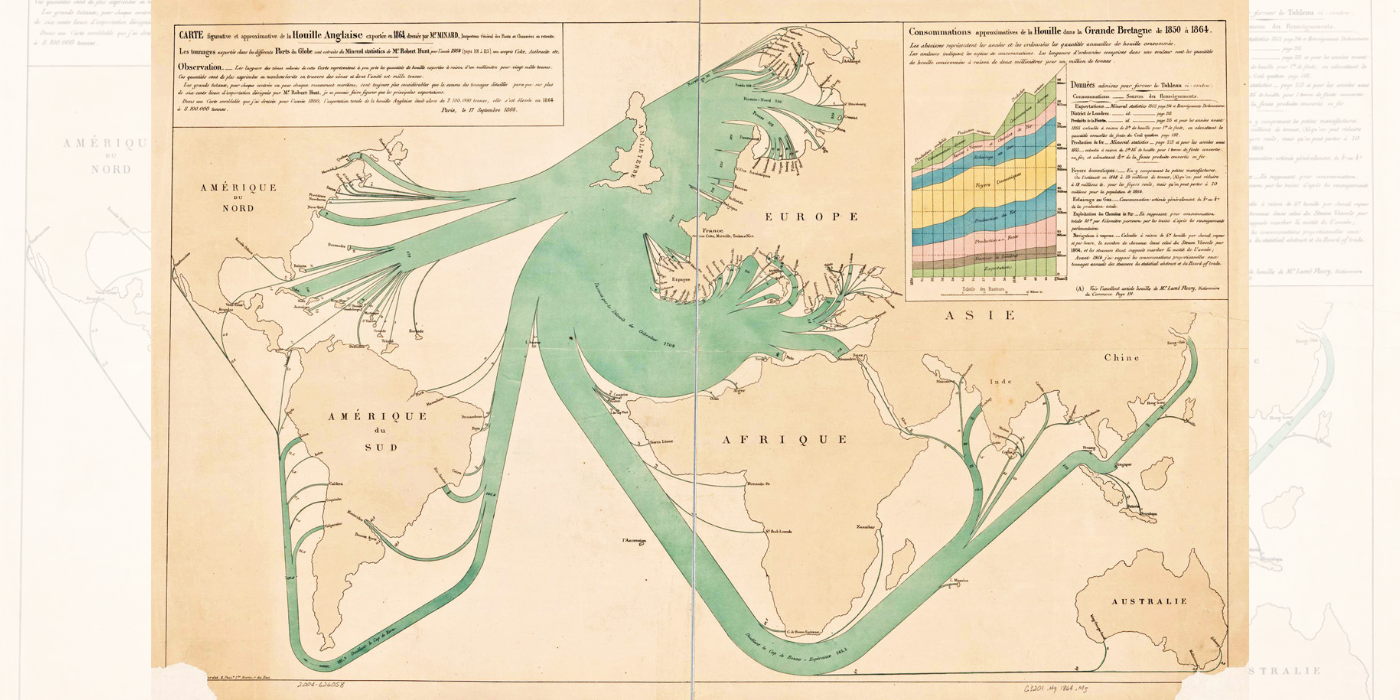

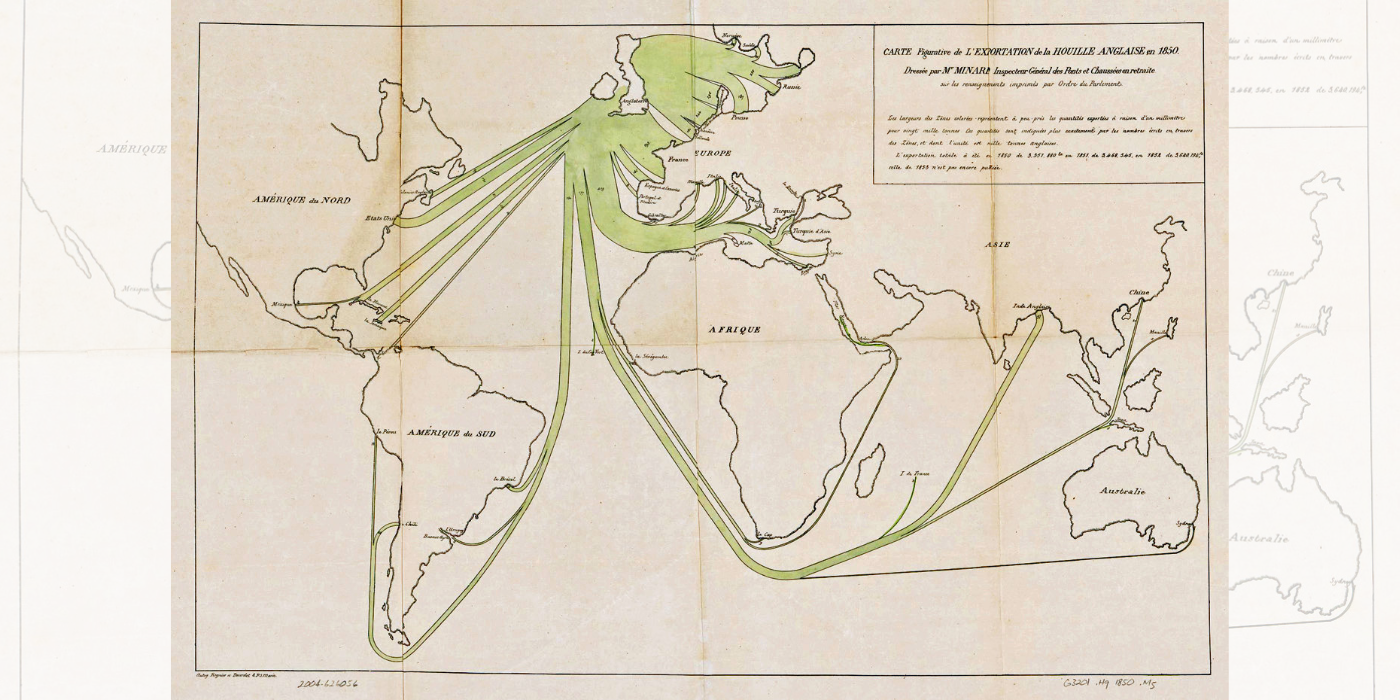

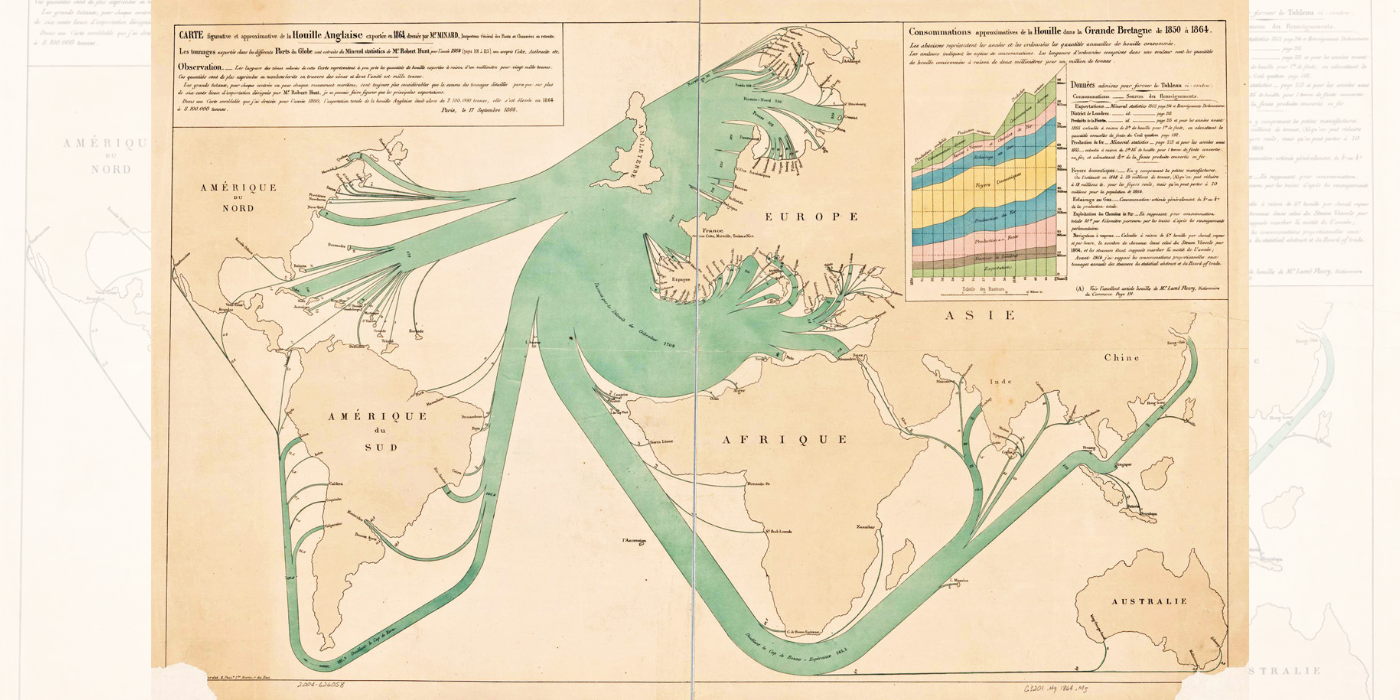

Across the world coal was increasingly in demand for numerous industries and also for coaling stations where steamships could refuel. Overseas exports of coal from Britain surged, eclipsing those of other countries (such as Australia and the United States) right up to the 20th century. Around 3 million tons of coal were exported globally in the mid-19th century, increasing to more than 95 million tons on the eve of the First World War.3 Being a relatively low-value bulky commodity, it was cheaper to ship coal by sail, especially in iron and steel sailing ships. The colliers that took coal from north-east England to London needed ballast for their return journeys, as there were no other cargoes, but ships carrying coal overseas would bring back a profitable cargo whenever possible.

Coal was often carried by tramp ships that had no regular routes, but were involved in flexible trade patterns, and Captain William H S Jones recorded one example at the start of his sailing career as an apprentice in the British Isles. Built in 1884, this three-masted steel ship was rated ✠100A1 by Lloyd’s Register, 4 and on his first voyage they criss-crossed the globe with different cargoes, leaving Port Talbot in June 1905 with 3,600 tons of South Wales coal. Their destination was round Cape Horn to Pisagua, Chile, and onwards to Callao, Peru, for an overhaul. In June 1906 they sailed in ballast to Sydney, Australia, for further maintenance, then went to Newcastle, New South Wales, for coal. By the late 19th century, this substantial coalfield was dominant in exporting coal in the southern hemisphere, especially across the Pacific to the west coast of South and North America. In late October the British Isles headed across the Pacific to Valparaiso, Chile, before returning to Newcastle in ballast and then to Mejillones, Chile, with another cargo of coal. Their next destination was Iquique, Chile, for nitrate, which was discharged at Dunkirk, France, in January 1908. 5

Coal exports by sea from Britain in 1850

Coal exports by sea from Britain in 1864

British Isles steel sailing ship

Coal exports by sea from Britain in 1850

Coal exports by sea from Britain in 1864

British Isles steel sailing ship

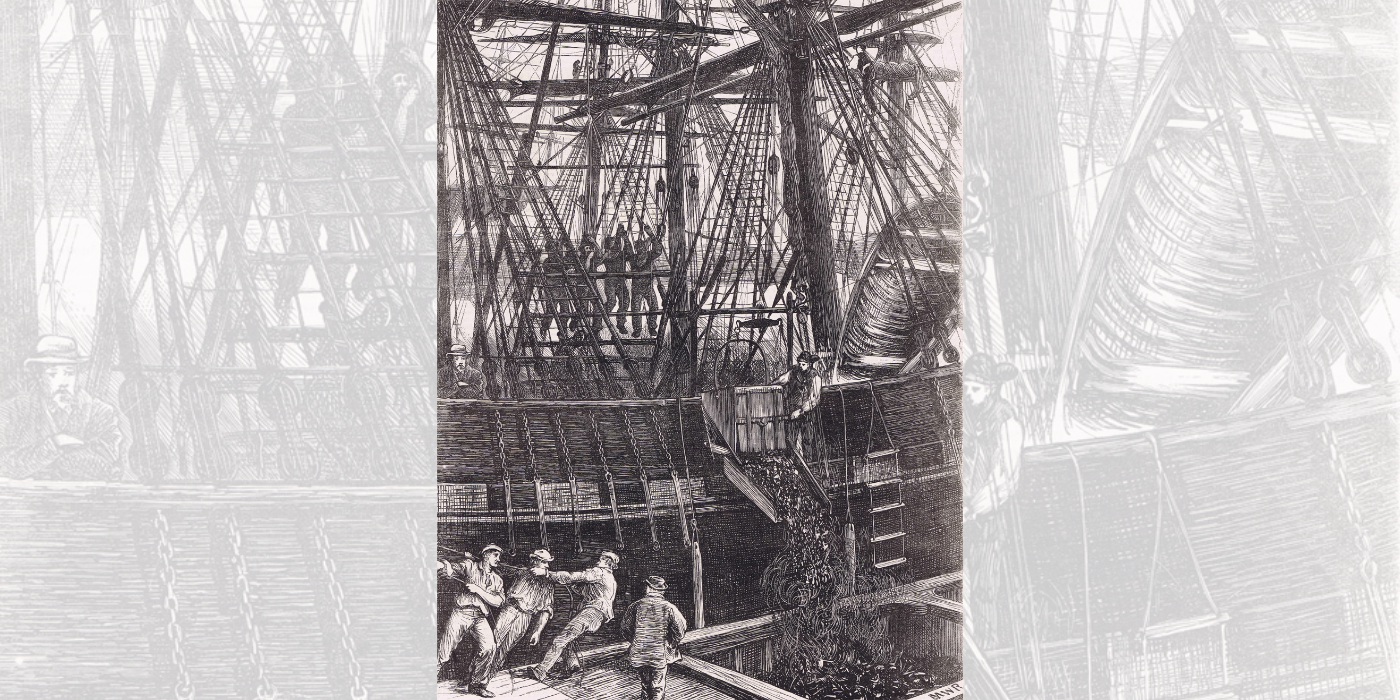

Mechanisation was gradually introduced to ports for the loading and unloading (discharging) of coal cargoes, but for much of history this was done manually, sometimes aided by ship’s equipment such as winches and donkey engines. Coal brought from mines in railway trucks to wooden staithes (wharves) was tipped down chutes through hatchways into a ship’s hold or else was tipped into keels or lighters for transferring to ships moored in deeper water. In the dark and choking conditions of the hold, the trimmers worked to ensure that the coal was evenly distributed to prevent it shifting during the voyage, making the ship unstable. One report summarised trimming as ‘filling the hold of the ship uniformly with coal, and in finishing off the heap of coal at certain points fore and aft by means of a wall of large pieces of coal’. 6 William Jones said that the work of trimmers was ‘perhaps the most important single item of technical skill and knowledge a Master required to sail his ship from port to port under the several conditions of wind and weather which could be encountered’. 7

At the destination port, one method of discharging coal was hoisting by a rope (whip) to which lanyards were attached. It involved several men in the hold shovelling coal into baskets or wooden tubs, which were hauled up and emptied into barges, lighters or carts. Writing in 1927 about life at sea decades earlier, the mariner Andrew Shewan explained how it worked:

A high stage was erected alongside the hatchway and extended to the vessel’s rail. On this three or more ‘coal whippers’ stood, each grasping one of the lanyards. At a given signal these men took two or three quick pulls together ... and then, the tub being the required height, still holding the lanyards, they leapt off the stage on to the deck. Their combined weight jerked the basket high enough for the ‘gangway men’ to lay hold of the rim and swing it to the bulwarks, where the contents were shot into a lighter alongside. It sounds simple, but in practice a long day at the job was a heavy enough task. 8

In 1871 The Graphic commented on coal being discharged by coal whippers from colliers in the Pool of London: ‘The operation is somewhat primitive ... The “whipper” ... is a sort of human lever for bringing out of the vessel’s hold the full basket of coal.’ Shewan added that coal whipping ‘constituted a phase of sea-life to which there is no counterpart nowadays’. 9

Collier discharging coal in the Pool of London

Coal whipping in the Pool of London at Rotherhithe

South Wales coalfield

Collier discharging coal in the Pool of London

Coal whipping in the Pool of London at Rotherhithe

South Wales coalfield

The South Wales ports such as Cardiff and Port Talbot expanded and developed, so that when Jones set sail from Port Talbot in the Caithness-Shire in September 1909, her cargo of 3,000 tons of coal had been loaded in only three days from railway trucks. By contrast, at Iquique, Chile, it took almost three months for six seamen and three apprentices down in the hold to shovel the coal into bags, which were hoisted up with the ship’s donkey engine and then lowered onto weighing scales and into lighters.10

Ports of call across the globe were invaluable for ship repairs and victualling, as well as for receiving orders for the discharge of cargoes, and they included strategically located islands in the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In the 19th century ports of call also acquired a vital role as coaling stations, providing coal to both merchant and naval steamships. Because coal was stowed in bunkers (compartments) on board steamships, the process became known as bunkering, while the coal was referred to as bunker coal or bunkers. British bunker coal, especially from Wales and north-east England, was in demand at coaling stations, with more than 20 million tons being exported in 1913. The Canaries alone took around a million tons for the thousands of steamships of many nationalities that called there to refuel. 11

Private companies operated most coaling stations and their coal was supplied by merchant vessels and stored on shore or in coal hulks (converted old vessels). Gibraltar became a thriving coaling station after the Suez Canal opened in 1869, with 19 coal hulks by the start of First World War. 12 The coaling of steamships worldwide took place from lighters or from jetties, often using local labour, including women and children. There was little mechanisation, so the coal heavers (or lumpers) carried coal up the gangways in baskets, or they filled sacks that were hauled up. At the island of St Thomas in the West Indies, one local resident in 1895 described the coaling process: ‘Busy as bees are the coal-women when at this exhausting labour; hundreds of them, each with a basket of coal on her head, run along the gangway leading to the steamer, empty it, and run back to have it once again refilled.’ 13 Bunker coal also needed trimming, and while coaling at Durban, South Africa, before the Second World War, Alex Hurst described the dangers facing the local trimmers: ‘Each wore a metal disc with a number on his wrist, and all were checked at the end of each shift, as in the past it had been no uncommon thing for some of these men to be buried in the coal and their corpses to be dug out en voyage.’ 14

The coaling station of Port Castries, St Lucia

Coaling tokens from St Lucia

Coaling at Brindisi, Italy

The coaling station of Port Castries, St Lucia

Coaling tokens from St Lucia

Coaling at Brindisi, Italy

When steamships were being refuelled, or when a cargo of coal was being loaded or discharged, coal dust covered everything, inside and out. While Annie Brassey was travelling round the world in 1876 in the steamer yacht Sunbeam, she went ashore at Montevideo, Uruguay, but on returning, ‘we found that the miseries of coaling were not yet over ... Everything on deck looked black, while below all was pitch black and airless, every opening and crevice having been closed and covered with tarpaulin, to keep out the coal dust.’ 15

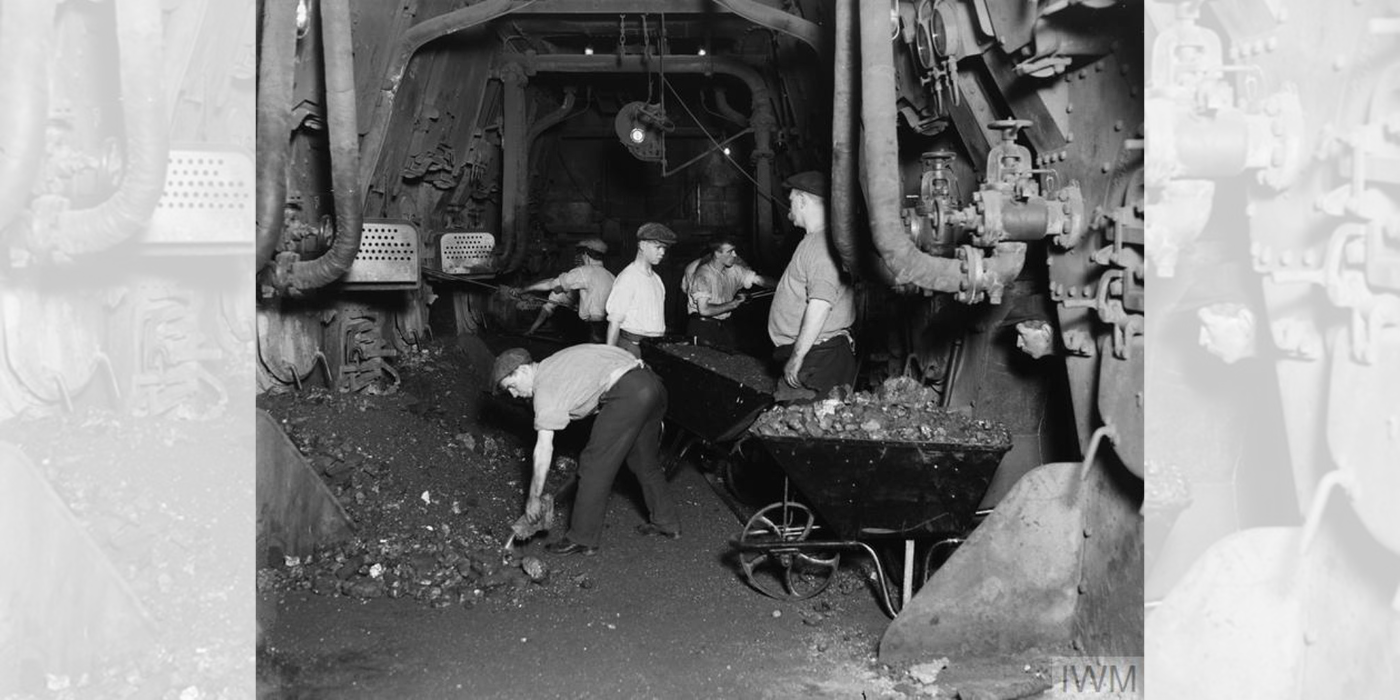

A steamship’s own coal trimmers and firemen (stokers) were known as the black gang, and they normally carried out their gruelling work in four-hour shifts or watches. Their numbers depended on the type of ship. In extreme heat in the stokehold, firemen kept the boilers going by shovelling coal into the furnaces and clearing out the clinker and ashes, which were dumped in the sea. The men were constantly thirsty, prone to fainting and at risk of burns and scalding. Because of the heat and filth, they wore as little as possible, just boots and a sweat-rag, possibly dungarees, and belts were positioned back-to-front to stop the buckles becoming red-hot. 16 One marine radio operator serving aboard tramp steamers recalled: ‘Coal-firing firemen were a race apart – long since extinct. I suspect that many of them are still feeding furnaces below. It used to be said that their sole gear on joining ship was a pack of cards and a sweat rag, and this was not far from the truth ... They were quite impervious to cold or heat and scared of nobody.’ 17

Joseph Maguire, an Irish doctor who served on board merchant ships, noted how, in the decades before the Second World War, the men’s health was affected:

Coal-burning ships recall for me the pitiful picture of blistered, fissured and often septic hands, or the image of a man with that agonising condition known as fireman’s cramp. The latter is due to excessive intake of cold fluids after a long spell of intense heat in the stokehold. The hands and feet are so contracted that they look like claws ... The condition occurs when there has been a severe loss of body salt through prolonged sweating.18

The bunkers were hot, airless and poorly lit with safety lamps to prevent explosions from gas seeping from the coal. In these conditions the trimmers fetched coal in wheelbarrows to take to the furnaces and ensured that the coal in the bunkers was constantly trimmed. The seafarer and writer Frank Thomas Bullen described the scene:

When the bunkers are full, and the great fragments of coal hurtle down their slopes around the toiling figure in a dense cloud of dust, quite obscuring his dim lamp, his position looks, as indeed it is, frightfully dangerous. Cuts and bruises are so plentiful that he ceases to notice them. He gets used to breathing an atmosphere that is largely composed of gas and coal dust.19

Stokehold of a merchant ship

Safety lamp used in coal bunkers

Stokehold of a merchant ship

Safety lamp used in coal bunkers

With no coal, a steamship without auxiliary sails was powerless, and yet it could be difficult assessing how much coal was left in the bunkers. The Atlantic liner was an iron steamship built in 1871 and rigged as a four-masted barque. In March 1873 she was proceeding to New York from Liverpool with hundreds of emigrants. After encountering bad weather, which slowed their progress and damaged the sails, the captain decided to divert to Halifax, Nova Scotia, for more coal, as he was uncertain if they had enough to reach New York. Fatal errors were made in navigation, and in the early hours of 1 April she ran aground at full speed on the rocky coast with the loss of 562 lives. 20

Coal mining was hazardous, but the dangers did not stop there, because many lives and ships were lost while carrying coal. Coal dust and small coal tended to choke the pumps needed for clearing water, and coal cargoes were prone to shifting in turbulent weather, causing ships to list or tip over. In some cases, crews managed to right their vessels by levelling the coal, but many more sank. In the roaring forties of the Pacific, the Cambrian Chieftain barque was bound for Coquimbo, Chile, with coal that had been loaded at Newcastle, New South Wales, but in mid-April 1894 she was thrown on her beam ends when the cargo shifted during severe weather. Incredibly, a look-out on board the three-masted barque Dee spotted the stricken vessel, and in mountainous seas they saved the captain’s wife and two children, as well as some crew members. In a second attempt, the rescue boat capsized, and as darkness fell the sinking ship was abandoned. The Dee reached Valparaiso in Chile in May, where the disaster was reported and a memorial service held for those who had perished. But the Cambrian Chieftain had not sunk, because her captain and depleted crew had continued trimming the coal and cutting away the sails and masts. After righting the vessel, they rigged jury masts (temporary masts), and in July they came in sight of land and were towed to Coquimbo by a steamer. The men from the Dee’s boat were never found – the second mate and four seamen, one from the Cambrian Chieftain. When the Dee finally reached Hull, the local newspaper reported the story, ending on a poignant note: ‘One of the first to board her was the mother of the unfortunate second mate, who had hoped against hope that her only son had, after all, escaped the icy embrace of the merciless waves.’21

A similar event occurred in May 1914, when the Glenholm steel sailing ship, built in 1896 and rated ✠100A1 by Lloyd’s Register, 22 sailed from Cardiff, Wales, with coal for Valparaiso, Chile, but near the River Plate they were hit by a pampero, a violent hurricane-force squall. Helen Campbell, the captain’s daughter, recorded that the port side of the ship was under water, forcing the crew to enter the hold to trim the coal cargo and right the ship, which took many days. Still with a heavy list, they continued their journey and arrived at Valparaiso just as the First World War began. 23

Stevedores were responsible for loading vessels and for the work of trimmers, and at ports such as Newcastle, New South Wales, cuts to their rates of pay were blamed on the deterioration in coal trimming. The masters of ships were equally blamed for not supervising the work properly. The Liverpool Journal of Commerce in 1894 gave a chilling assessment:

In other words, ships are knowingly permitted to proceed to sea by stevedores who are well aware of the great chance run by them of capsizing during the first gale, or in the first heavy squall ... No wonder ship masters require shifting-boards ... Any man who knowingly lets a badly trimmed ship sail, and she does not reach her destination, must feel like one guilty of manslaughter.24

Calls for compulsory vertical shifting boards to contain coal and prevent it moving had long been voiced, and a few years earlier, in 1887, a paper presented to the Institution of Naval Architects was concerned that they were not compulsory:

It is difficult to understand why coal cargoes have been so long exempt from the restrictive legislation to which other cargoes which shift are subject. Statistics appear to show that they need it quite as much. During the three years ending 1877, 300 coal-laden British vessels foundered or were missing, and with them were lost 991 lives ... in the triennial period ending 1883 the number of vessels rose to 314, and the lives reached the melancholy total of 1,849. 25

Benjamin Martell was a naval architect and Chief Surveyor of Lloyd’s Register, and he was in the audience. In his response he said that although many coal-carrying ships went missing, defective hulls may have been the cause in the case of old colliers. Even so, he was sure that most were lost for two reasons – the shifting of the coal cargo and fire. 26 By fire, he was referring to the greatest danger of coal as a cargo – the terrifying incidents of fires caused by self-combustion, which will be looked at in ‘Coal at Sea: The hazards of overheating, fire and explosion’.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Lloyd’s Register Group or Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

Footnotes

-

1

Henry Stanley Jevons 1915 The British coal trade (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co; New York: E P Dutton & Co); M J Bradshaw 1973 (2nd ed) A new geology (London: Hodder & Stoughton), pp 99–102; H M Hoar 1930 The coal industry of the world, with special reference to international trade in coal (Washington: Government Printing Office), pp 8–12, 296.

-

2

Steam engines were powered by the pressure of steam created by heating water in a boiler using coal as a fuel. For the development of steam power, see Jevons 1915, pp 44–57. For the coal industry across Britain, see Barrie Trinder 2013 Britain’s Industrial Revolution: The making of a manufacturing people, 1700–1870 (Lancaster: Carnegie Publishing), pp 203–90. For the coastal coal trade, see Basil Greenhill 1957 The Merchant Schooners, volume II (London: Percival Marshall), pp 74–96, and Michael Stammers 2007 The industrial archaeology of docks & harbours (Stroud: Tempus).

-

3

G R Porter 1851 (new edn) The Progress of the Nation, in its various social and economic relations, from the beginning of the nineteenth century (London: John Murray) gives 2,828,039 tons exported to foreign countries and British colonies for 1849 (p 279); B R Mitchell and Phyllis Deane 1962 Abstract of British historical statistics (Cambridge: University Press) give 3,212,000 tons for 1850 and 73,400,000 tons for 1913 (p 121); Michael Stuart Clark 2007 ‘Coal Export’ pp 420–2 in John B Hattendorf (ed) The Oxford encyclopedia of maritime history Volume 1 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press) gives 11 million tons for 1850 (which must include coal shipped to British and Irish coastal ports) and 77 million tons for 1913, including bunker coal; Jevons 1915 gives 97,719,000 tons for 1913, including 20 million tons for foreign bunker coal (p 676); Hoar 1930 gives 95.67 million tons for 1913, including coal, coke and bunker coal, with a further 2.05 million tons of ‘manufactured fuel’(p 91).

-

4

See Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, from 1st July, 1905, to the 30th June, 1906, volume II. Sailing Vessels (London).

-

5

William H S Jones 1956 The Cape Horn Breed: My experiences as an apprentice in sail in the fullrigged ship “British Isles” (London: Andrew Melrose), pp 32–264; George H Kingswell 1890 The coal mines of Newcastle, N.S.W. Their rise and progress (Newcastle, N.S.W.).

-

6

Report of the Royal Commission appointed to inquire into the dangers to which vessels carrying coal are said to be peculiarly liable, and as to the best means that can be adopted for removing or lessening the same 1897 (Sydney, New South Wales), p 15. For trimmers, see pp 32–3 of Michael Clark 2006 ‘”Bound Out for Callao!” The Pacific coal trade 1876 to 1896: Selling coal or selling lives? Part I’ The Great Circle 28, pp 26–45; see p 12 of Michael Clark 2007 ‘”Bound Out for Callao!” The Pacific coal trade 1876 to 1896: Selling coal or selling lives? Part II’ The Great Circle 29, pp 3–21.

-

7

W H S Jones 1969 All hands aloft! (London: Jarrolds), p 43.

-

8

Andrew Shewan 1927 The great days of sail: Reminiscences of a tea-clipper captain (London: Heath Cranton), pp 88–9. See also W S Lindsay 1874 History of Merchant Shipping and Ancient Commerce vol II (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low, and Searle), pp 535–7; and Stammers 2007, p 91.

-

9

The Graphic 25 February 1871, p 174; Shewan 1927, pp 88–9.

-

10

Jones 1969, pp 42, 138–9, 146–50. See also John Richards 2005 Cardiff: A maritime history (Stroud: Tempus), pp 137–50.

-

11

Steven Gray 2018 Steam power and sea power: Coal, the Royal Navy, and the British Empire, c.1870–1914 (London: Palgrave Macmillan); Christopher James Allan 2020 Coal as a freight, coal as a fuel: A Study of the British coal trade: 1850–1913 (Durham University thesis); Peter Adam Shulman 2007 Empire of energy: environment, geopolitics, and American technology before the age of oil (Massachusetts Institute of Technology dissertation); W E Minchinton 1976 ‘British ports of call in the nineteenth century’ The Mariner’s Mirror 62, pp 145–58 (see pp 149–52 for coaling stations); and Walter E Minchinton 1984 ‘The Canaries as ports of call’ pp 273–9 in VI Coloquio de Historia Canario Americana (Las Palmas) (see especially pp 286–9).

-

12

See Richard J M Garcia 2022 Making a Difference: The life and times of John Mackintosh (Gibraltar: Trustees of the Estate of John Mackintosh), which gives a detailed description of the coaling trade at Gibraltar, focusing on Mackintosh.

-

13

Charles Edwin Taylor 1895 An island of the sea, descriptive of the past and present of St. Thomas, Danish West Indies (St Thomas), p 34. Taylor was a medical physician and resident. For coaling by women, see Gray 2018, pp 140–5.

-

14

Alex A Hurst 1992 A succession of days (Worcester: Square One Publications), p 56. He was serving on board the Raranga, a twin-screw coal-burner of 10,000 tons.

-

15

Mrs Brassey 1878 Around the world in the yacht ‘Sunbeam’: our home on the ocean for eleven months (New York: Henry Holt and Company), p 66; see also Denis Chadwick 1982 ‘Cargoes’ pp 19–22 in Ronald Hope The seaman’s world: Merchant seamen’s reminiscences (London: Harrap and The Marine Society).

-

16

For firemen and trimmers, see Alston Kennerley 2008 ‘Stoking the Boilers: Firemen and Trimmers in British Merchant Ships, 1850–1950’ International Journal of Maritime History 20, pp 191–220 (for buckles, see p 220); Edward Marriott 1974 ‘When ships burned coal’ Sea Breezes 48, pp 182–5; Denis Griffiths 1997 Steam at Sea: Two centuries of steam-powered ships (London: Conway Maritime Press), pp 132–6; and F T Bullen ‘The slaves of steam’ Morning Leader supplement 13 May 1899, p 3. More than 100 firemen or stokers worked in big liners (George Blake 1960 Lloyd’s Register of Shipping 1760–1960 (London: Lloyd’s Register of Shipping), p 87.

-

17

John Moody 1982 ‘Today and Yesterday’ pp 75–8 in Hope 1982. John T W Moody was a Marconi marine radio operator from 1936 to 1979.

-

18

See p 70 of J B Maguire 1984 ‘Doctor at Sea’ in Ronald Hope (ed) Sea Pie: A celebration of 50 years of ‘The Seafarer’ (London: Fairplay Publications & The Marine Society), pp 69–72; Joseph B Maguire 1957 The Sea My Surgery (London: Heinemann), p 54.

-

19

Bullen 1899.

-

20

The Atlantic was built at Belfast by Harland & Wolff. She did have enough coal, but there was confusion between what was actually in the bunkers and what was recorded in the log. See C H Milsom 1975 The coal was there for burning (London: The Institute of Marine Engineers); Griffiths 1997, pp 135–6.

-

21

A G Course 1950 The wheel’s kick and the wind’s song (London: Percival Marshall), pp 99–101; The Advertiser (Adelaide) 25 August 1894, p 5; Hull Daily Mail 24 September 1894, p 3.

-

22

See Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, from 1st July, 1896, to the 30th June, 1897, volume II. Sailing Vessels (London). The Glenholm was a full-rigged stump topgallant ship of 1,804 tons, built of steel in 1896 at Port Glasgow.

-

23

See p 916 of Claude L A Woollard 1965 ‘Schoolgirl under Sail (2)’ Sea Breezes December 1965, pp 914–21.

-

24

The Liverpool Journal of Commerce 11 December 1894, pp 4–5.

-

25

See p 369 of Philip Jenkins 1887 ‘On the shifting of cargoes’ Transactions of the Institution of Naval Architects 28, pp 359–78; Francis Elgar 1887 ‘Notes upon losses at sea’ Transactions of the Institution of Naval Architects 28, pp 53–124; Clark 2006, pp 37, 38–40. For the quality of trimmers, see Clark 2007, pp 8–10, 12–13, 15–16.

-

26

Jenkins 1887, p 372; Nigel Watson 2010 Lloyd’s Register: 250 years of service (London: Lloyd’s Register), p 31. Martell was Chief Surveyor from 1872 to 1900.