Coal has always been a hazardous cargo, and gas explosions and spontaneous combustion were the two most serious causes of danger to ships, crews, passengers and cargoes. In the second half of the 19th century, many more ships laden with coal were lost than with any other cargo.

As early as September 1753 Captain Thomas Francis of the Pearl merchant ship gave a warning about carrying coal at sea. When they came within sight of Cape Charles, Virginia, after sailing across the Atlantic for two months from Port Glasgow with passengers and a cargo that included coal, he was horrified to see smoke issuing from the hold. They managed to extinguish the fire, but a great deal of damage had been done: ‘I take the cause of this to have been the sulphur in the coals; which may serve as a caution to those who send coals on a long voyage, not to take such as have a great quantity of sulphur in them.’ 1

In the second half of the 19th century, with an ever-growing demand for coal across the world, many merchant ships were involved in the trade, with a substantial proportion registered in Britain. In 1866 the Salvage Association of Lloyd’s of London published a report on spontaneous combustion, and in 1875 a Royal Commission looked into the topic, which was also examined again during an 1885 Royal Commission on loss of life at sea. Another investigation was held in Australia in 1896, as insurance companies were reluctant to underwrite ships if the coal was from Newcastle, New South Wales. Recommendations from these and other reports were repeatedly made – coal was not to be broken up by manhandling from the pit to the hold, wet coal should be avoided, the temperature of the coal needed to be monitored, and ventilation was paramount. 2

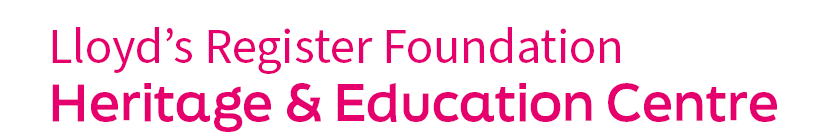

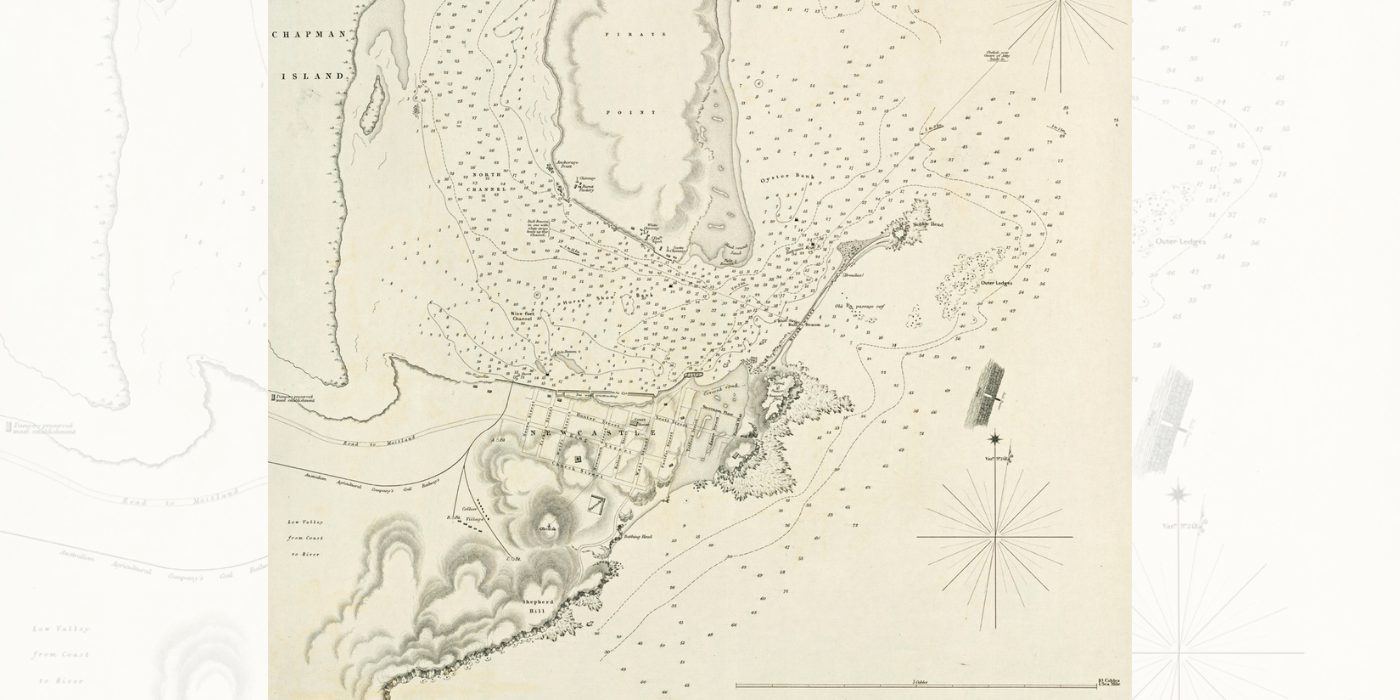

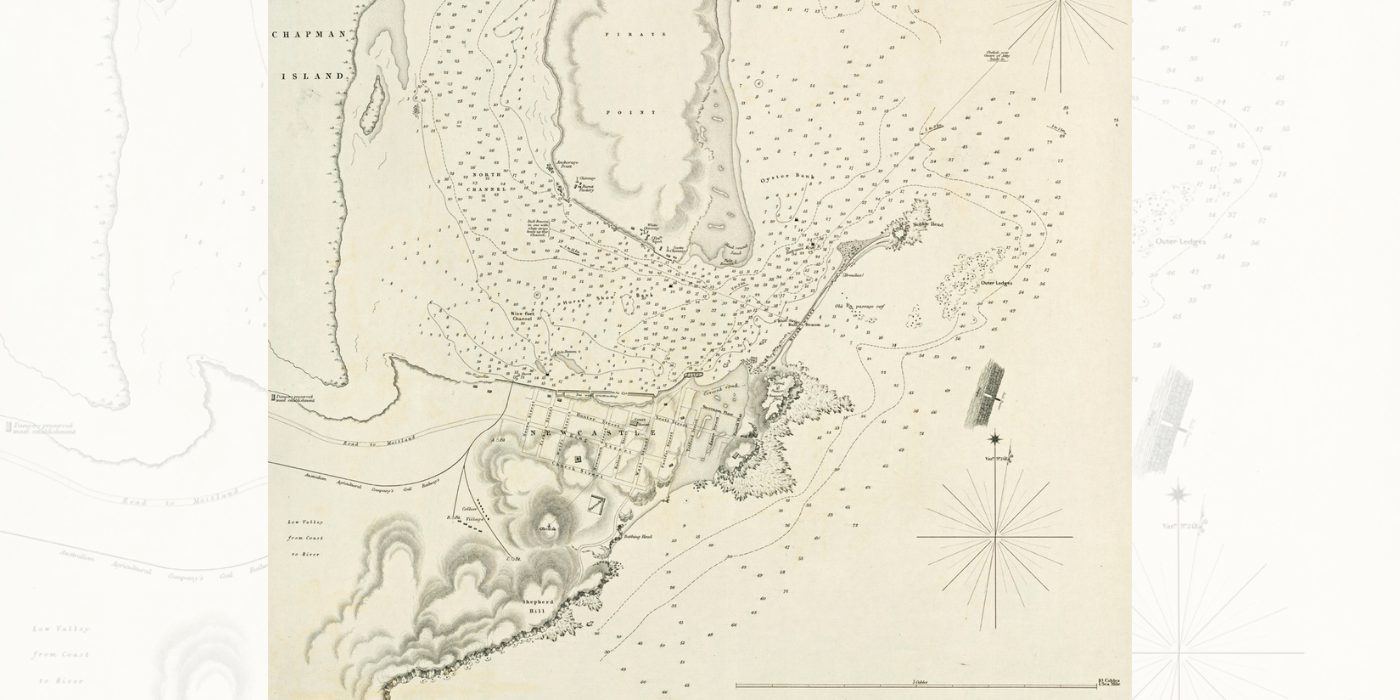

Coal at Newcastle, New South Wales

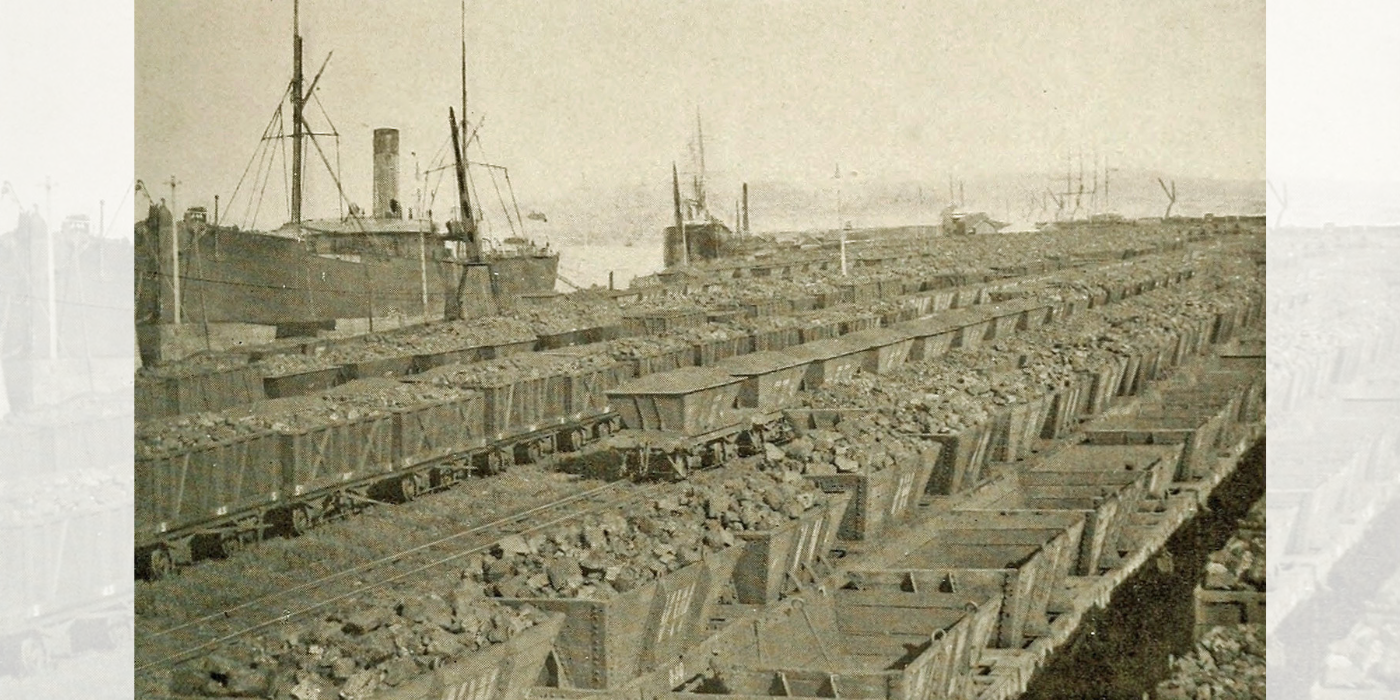

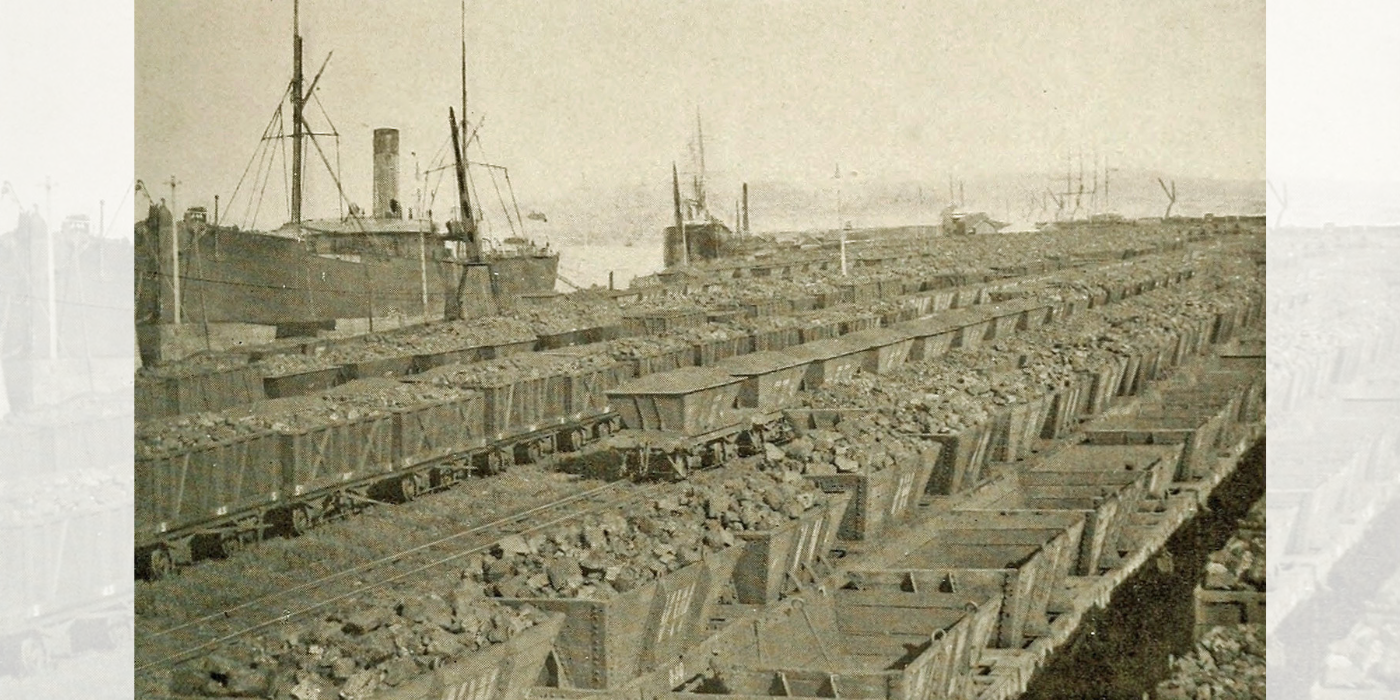

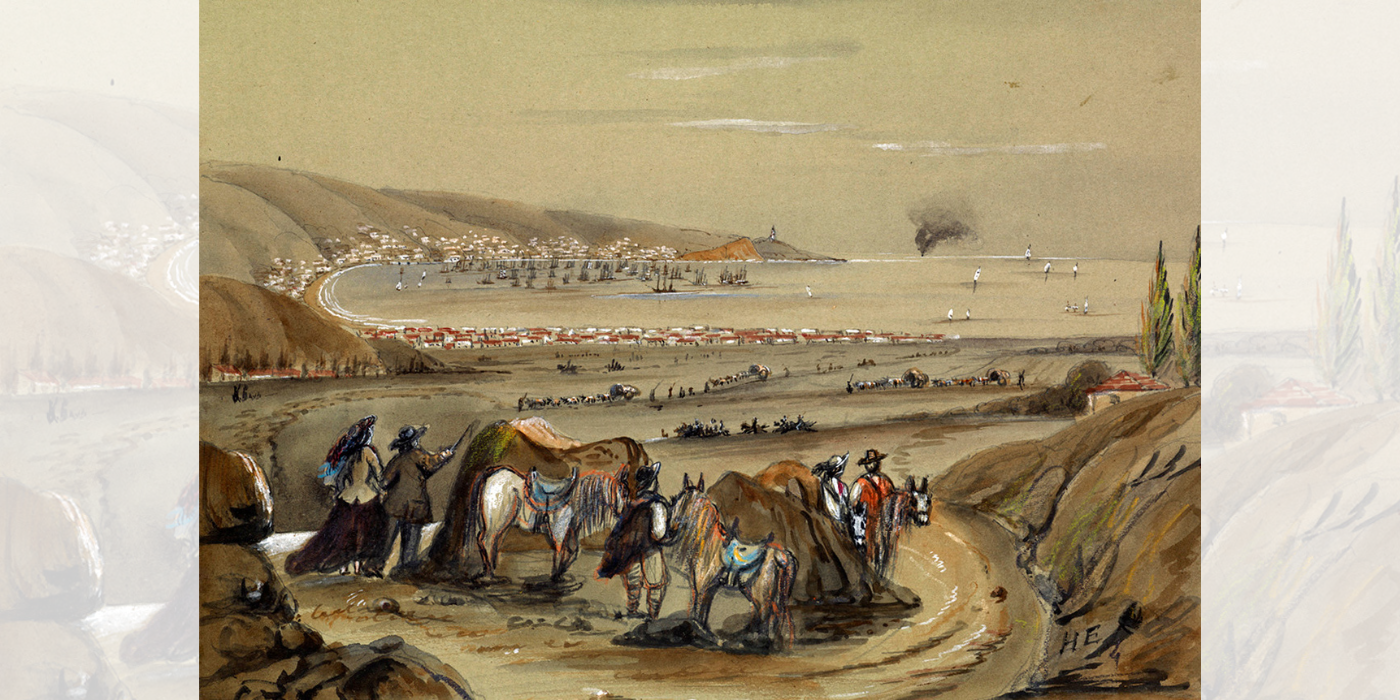

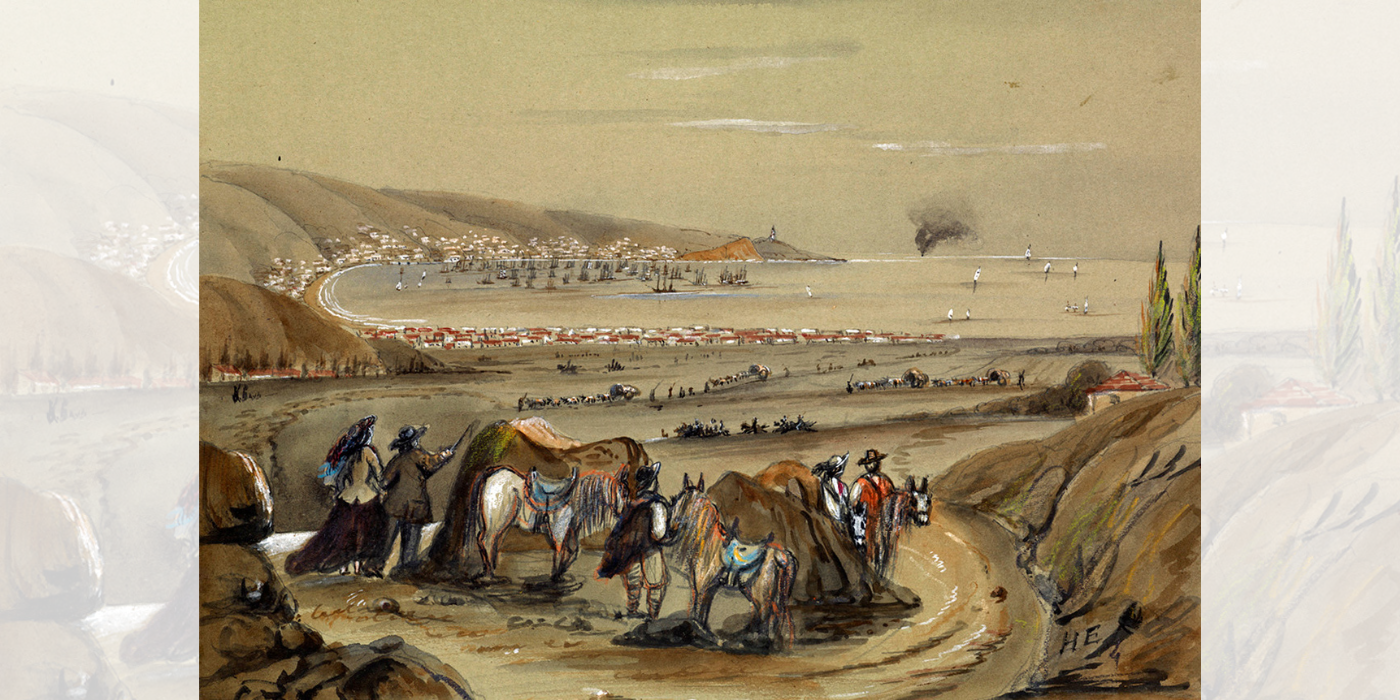

Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia in 1851

Coal at Newcastle, New South Wales

Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia in 1851

Coal mining was a perilous occupation, though the invention of safety lamps in the early 19th century reduced the number of pit explosions caused by naked flames and allowed miners to detect the most dangerous gases. After coal was loaded on board ships, it remained hazardous, particularly if recently hewn. In the confined space of a hold, volatile gases from the coal could accumulate and explosions occur a few days after loading, due to sparks or naked flames like candles and matches, not to spontaneous combustion. It was therefore essential for hatches to be left open as long as possible at the start of a voyage, and safety lamps were recommended for the holds and bunkers.3

Countless explosions nevertheless occurred. On 19 November 1878 the steamship Richmond left the port of Penarth, in South Wales, loaded with 1,233 tons of newly wrought ‘Ocean Steam Coal’, a hard semi-anthracite coal. She was bound to Malta, but severe weather in the Bay of Biscay meant closing and battening down the hatches, leaving her two holds without ventilation. 4 The Government Inspector of Mines for South Wales said that coal from the collieries of the Ocean Steam Company was ‘fiery’ and prone to emitting gas for a few days after being worked, so that ships needed ventilation in the form of one or more tubes going through the deck and into each hold, rather than relying on hatches that had to be closed in heavy weather. ‘Without ventilation,’ he added, ‘the hold of a ship laden with coal is simply a great gas-holder, and the presence of a large body of highly inflammable gas, pent up in an air-tight space, exposes the lives of the persons on board and the ship to destruction.’5 The Richmond’s four ventilating bollards were not functioning, and five days after sailing an explosion in one hold caused so much damage and injuries that the vessel was abandoned off Cape Finisterre. The Wreck Inquiry believed that the explosion was set off by the steward entering the lazarette with a lighted candle.

Another danger was the tendency of coal to heat up, smoulder and self-ignite (‘spontaneous combustion’) through oxidation, in which coal absorbs oxygen from the air and produces heat. When the coal reaches a critical temperature, fires and explosions occur. Caused by varying and complex physical and chemical processes, spontaneous combustion has long been a problem, not just for cargoes but the entire coal industry, including at abandoned mines and spoilheaps. Pinpointing precise reasons has always been difficult. 6 When tipped from a height down small hatchways into a hold, coal would break into smaller pieces, making the cargo more liable to oxidation. Some types of coal were especially vulnerable, including that containing quantities of iron pyrites, and the area beneath hatchways was most at risk, because smaller pieces accumulated there. 7 In the 1866 report on spontaneous combustion, Captain James Heathcote explained: ‘The coal shipped from Swansea for the West Coast of South America is almost exclusively the bituminous, commonly called “binding” coal, used there in conjunction with the coal of the country for smelting copper ores.’ Because the larger pieces were held back to sell as house coal, what was actually shipped were smaller pieces more liable to spontaneous combustion. 8

Smouldering coal

Coal on fire

Smouldering coal

Coal on fire

Seafarers frequently declared that coal was more dangerous if loaded when wet or became damp in heavy seas, including Captain Henry Scott from Newcastle-on-Tyne, who told the Royal Commission in 1875 that ‘coals shipped wet are the greatest danger of all’. Henry J Bath at Swansea had business interests in shipping and the copper trade with Chile, and he highlighted the danger: ‘Smelting coal is in its very nature soft and is shipped as it is worked, with a large proportion of small. In this moist climate this coal, even when protected from actual wet, does always contain a certain amount of moisture.’ His own vessels were provided with ventilation, and he had experienced no problems even though they shipped between 30,000 and 40,000 tons to South America each year. 9

On 22 July 1876 the Monkshaven wooden barque left Porthcawl, near Swansea, with smelting coal bound for Valparaiso, Chile, and on 23 September the coal was found to be alight.10 The crew tried to dig down into the coal, but the heat became more intense the deeper they went, so that several men had hands or fingers burned. The next day they threw overboard anything combustible, such as tar, oil and spare sails, and battened down the hatches. The plan was to reach Montevideo and save some of the cargo, but they almost gave up hope after suffering a terrible gale. And then the Sunbeam steamer yacht appeared, in which Mrs Annie Brassey and her husband Thomas were travelling round the world. Not long after leaving Buenos Aires on 28 September, the Sunbeam spotted the stricken vessel with her red union-jack upside-down and signals of ‘ship on fire’, followed by ‘come on board at once’. Using a telescope, they made out her name – the Monkshaven of Whitby. 11

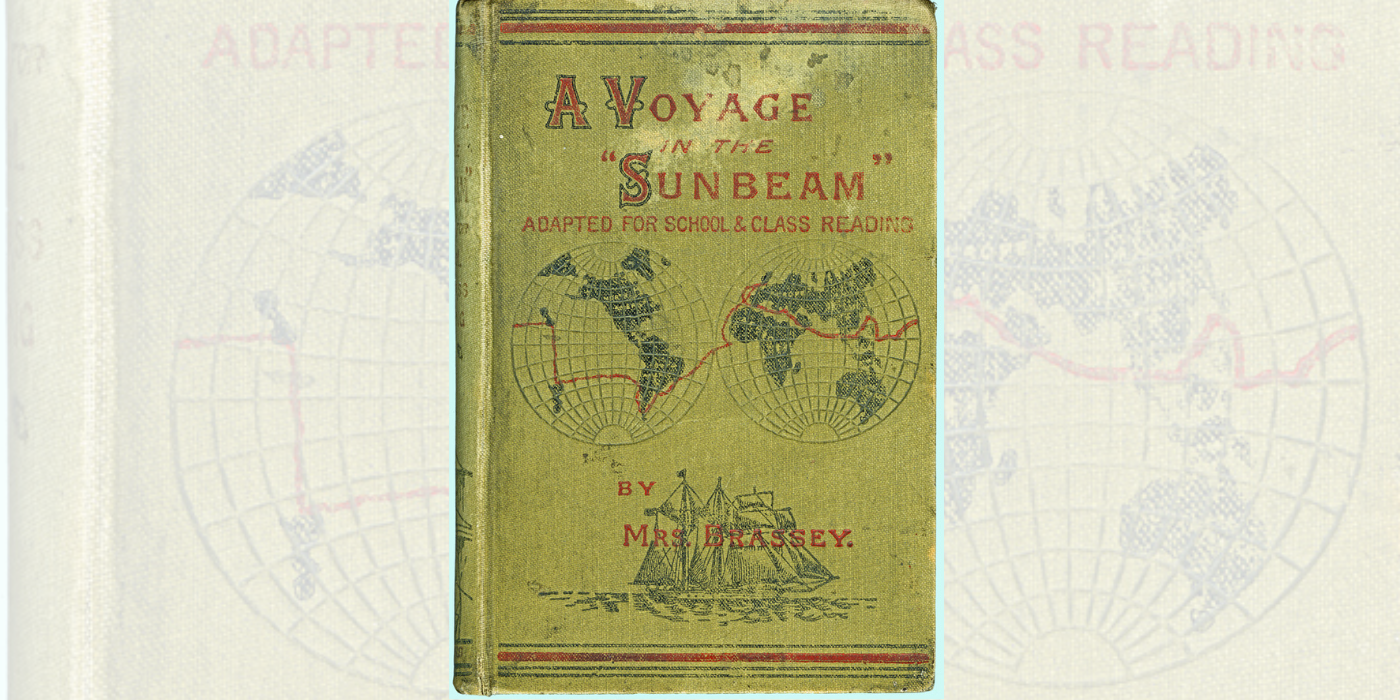

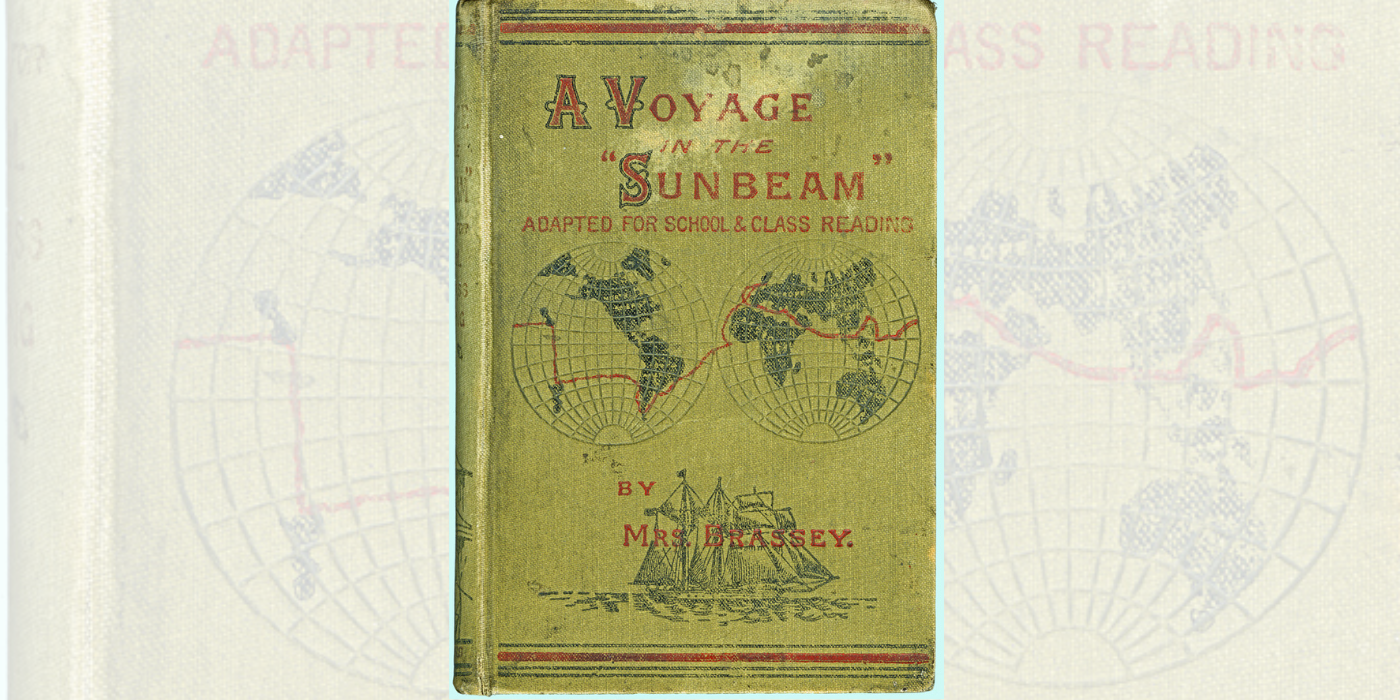

The Sunbeam steamer yacht

Book jacket of the Sunbeam’s world voyage

The Sunbeam steamer yacht

Book jacket of the Sunbeam’s world voyage

Thomas and the Sunbeam’s captain rowed across to the Monkshaven just as a puff of smoke rose up:

They found the deck more than a foot deep in water ... when the hatches were opened for a moment dense clouds of hot suffocating yellow smoke immediately poured forth, driving back all who stood near. From the captain’s cabin came volumes of poisonous gas ... and one man, who tried to enter, was rendered insensible. It was perfectly evident that it would be impossible to save the ship. 12

After rescuing the crew, everyone watched the fire spread: ‘For two hours we could see the smoke pouring from various portions of the ill-fated bark. Our men ... reported that, as they left her, flames were just beginning to burst from the fore-hatchway.’ Later on the Sunbeam steamed round the wreck: ‘No flames were visible then; only dense volumes of smoke and sparks, issuing from the hatches. The heat, however, was intense, and could be plainly felt ... All hands were clustered ... to see the last of the poor “Monkshaven,” as she was slowly being burned down to the water’s edge.’ 13

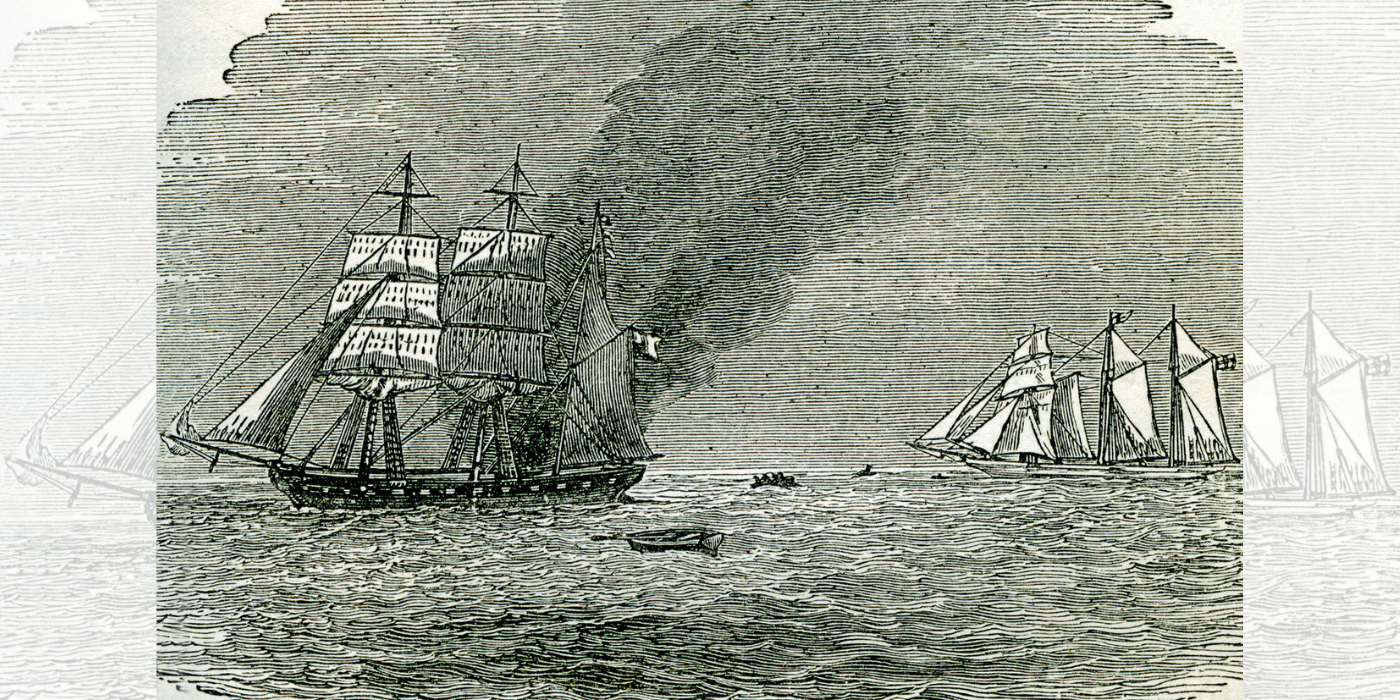

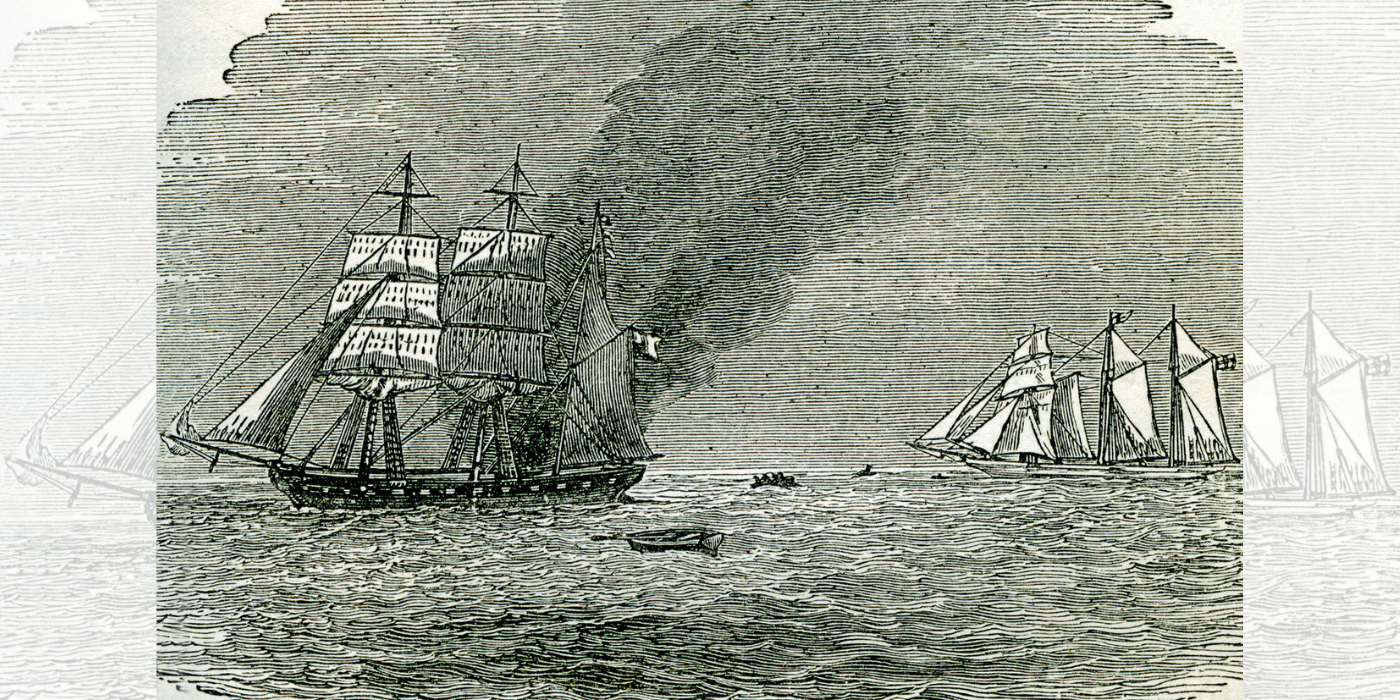

The Monkshaven on fire

Valparaiso, Chile, in about 1856

The Monkshaven on fire

Valparaiso, Chile, in about 1856

Eyewitness accounts tend to be from survivors or chance observers like Mrs Brassey. Another vivid description of spontaneous combustion was written by Mrs Dolly Bradford Bates. In July 1850 she accompanied her husband, William Bates, captain of the American ship Nonantum of Boston, from Baltimore bound to San Francisco with a cargo of 1,050 tons of coal from the Cumberland Coal Company. ‘She was loaded very deep with coal,’ Mrs Bates said, ‘which was brought directly down to the ship, turned (sometimes soaking wet) directly into the ship’s hold.’ Several weeks later the crew detected smoke and so battened down the hatches and caulked the seams, but to no avail: ‘Each day the ship was getting hotter; gas and smoke was escaping at every seam. We constantly feared an explosion.’ Before such a catastrophe occurred, they reached the Falkland Islands, though Mrs Bates was to experience further terrifying incidents of spontaneous combustion of coal on board two other ships before reaching Peru. 14

Smoke seeping from the hatchways was generally the first sign of smouldering coal, or else the smell of smoke and gas might be detected, said by witnesses ‘as being similar to “paraffin oil,” “naphtha,” “coal tar,” “sulphur smell,” and like ordinary gas (coal gas)’. When sailing from Sunderland to Madras in 1852, Captain Henry Scott described that the coal cargo started smoking, and so his crew drove pointed iron rods into it and marked the hottest parts with chalk, from which the source of the fire was reckoned to be 10 feet down in the lower hold, directly beneath the hatchway. The ship was saved by removing the hot coals and setting up a cooling system with sails, and Scott urged any ship embarking on a long voyage to probe the coal frequently with ¾-inch rods of iron as a means of fire prevention. 15

Nowadays the temperature of coal cargoes is constantly measured to detect problems. Thermometers were used on occasions in the past, lowered into metal tubes or pipes that penetrated the coal, but Captain George Steinson, inspector for the Peninsular and Oriental Company at Newcastle-on-Tyne, told the 1875 Royal Commission that taking daily temperatures was not customary: ‘I spoke to some captains of ships about carrying a thermometer with them, and they said it would be a very expensive thing, but a thermometer only costs a couple of shillings, and they also said it would be an expensive thing to put down a tube, but that would not cost much.’ 16 A decade later, William Ramsden Price, a Lloyd’s underwriter and shipowner, described how his ships had 3-inch iron pipes inserted through the cargo:

We pass down these iron pipes a registering thermometer and taking the readings of it daily and comparing them ... you can see at a glance whether the temperature is increasing ... You can see at a glance where the mischief is. Then if you want to localise it more minutely, we supply them with some iron rods which they drive down into the cargo and leave them there for half an hour and they put their hand to them, and you can detect to a nicety where the heating is. 17

The most common method of dealing with overheating coal was to batten down the hatches in order to starve the hold of oxygen. The next step was for the crew to dig out the hot, smouldering coal in the hold in unbearable conditions, perhaps while pouring in seawater or even flooding the hold. Captain Scott said that when they dug down about 7 feet, ‘we came upon the coal so hot that the man at the bottom could only remain a short time, and had to be replaced at short intervals owing to the great heat and smoke and putting his feet into wooden boxes which we made to save from burning them’. 18 When William Jones was on board the British Isles as an apprentice in July 1906, their coal cargo began smouldering, and he vividly described digging it out and successfully dealing with the fire:

Coal-shovelling is hard enough work without being half-suffocated at the same time and having one’s boots shrivelled by standing on a hot bed while working. The heat scorched the soles of our feet, as we frantically hopped from one foot to the other to obtain a moment’s relief ... Now, as the shovellers neared the seat of the combustion, the heat became almost intolerable. Hundreds of buckets of water were poured down into the hold, giving temporary relief, but soon evaporating to steam which made the humidity intense ... On the fourth day, we reached the seat of the fire, where the coal was smouldering and smoking. Some of it burst into flame while being hoisted in the baskets. It was dumped overboard. 19

He also mentioned that firefighting was primitive: ‘In a sailing ship there are no steam-injections or fire-hoses and pressure pumps. The only alternative was either to close all ventilation in the hope of smothering the fire, or to open the hatch and dig the coal out.’ 20 Ships might have canvas hoses operated by hand pumps or donkey engines, while canvas and wooden buckets were always present, as well as pumps to remove water from the bilges, though they were easily clogged by coal dust and in danger of burning. Nothing was adequate in the face of a serious fire, and as a last resort a ship might be scuttled or abandoned.

The author Joseph Conrad spent years at sea, including as second mate in the wooden barque Palestine when carrying coal from North Shields bound to Bangkok. In the Indian Ocean in March 1883 it was realised that the cargo was on fire, and Conrad later dramatised the events in a novella called Youth, first published in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine in 1898. 21 Although he alters events, and the ship becomes the Judea, his descriptions are true to life. After failing to smother the fire, it was decided to use water, which meant removing the hatches and releasing volumes of smoke, ‘whitish, yellowish, thick, greasy, misty, choking’. He then gives an idea of the futility of the firefighting equipment: ‘We rigged the force-pump, got the hose along, and by-and-by it burst. Well, it was as old as the ship––a prehistoric hose, and past repair. Then we pumped with the feeble head-pump, drew water with buckets, and in this way managed to pour lots of Indian Ocean into the main hatch.’ Even after a huge explosion, the captain of the Palestine was reluctant to abandon ship, as he wanted to try to run the vessel on shore and save her by scuttling. 22

After the Nonantum with Mrs Bates reached Port Stanley at the Falkland Islands, her husband opened the hatches, but the fire continued raging, and he decided to scuttle her: ‘They cut holes in her side, and sank her in depth of water sufficient to cover the fire. For two days she was enveloped in steam ... After the fire was extinguished, they stopped the holes, and worked the pumps incessantly.’ This proved useless, and the Nonantum was condemned, being too badly damaged. 23 In November 1850 Mrs Bates and the crew left the Falklands on board the Humayoon, a Greenock-registered ship bound to Valparaiso from Dundee with a cargo of coal, tar and liquors. 24 As they went round Cape Horn, 80 miles from land and in a terrific gale, she was terrified when the coal cargo caught fire. The blaze spread rapidly, and they were forced to abandon ship, but were luckily rescued by the Symmetry of Liverpool, also laden with coal, from which they watched the disaster unfold: ‘Soon the main and mizen-mast began to totter: they swayed to and fro for about ten minutes, when they fell with a crash over the side. Soon the fore-mast fell; and all that remained of the fine ship “Humayoon” lay a burning mass upon the water.’ The Symmetry was short of supplies, so they were soon transferred to a large American ship, the Fanchon of Newburyport.25

The Fanchon had left Baltimore three weeks after the Nonantum and was loaded with 1,200 tons of Cumberland coal bound for San Francisco. Captain Lunt assured Mrs Bates that his vessel was well ventilated and could not catch fire, but on Christmas Day she recorded that ‘a puff of air was wafted into the cabin, so strongly impregnated with gas as to render the conviction certain in my mind, that the coal was on fire’. She was told this was not the case, but three days later Captain Lunt saw smoke coming from a ventilator on deck and ordered the second mate to dig down into the coal: ‘The coal was so hot, it could not be taken in the hand. The whole body of coal, two or three feet below the surface, was red hot.’ They were 1,200 miles from land and now made preparations to abandon ship, but for three weeks managed to continue sailing, meeting no other vessel. Smoke and gases escaped from every seam, and everything became blackened: ‘The beautiful paint-work and gilding of the cabin assumed the darkest hue; everything on board seemed shrouded in the sable habilments of mourning.’ 26 Suddenly land was spotted, the uninhabited Bay of Sechura, Peru, where Captain Lunt tried to save his ship by scuttling:

After removing everything off the ship’s deck, they ... scuttled her; but the fire had made such progress, it was impossible to save her. In two hours after we left her deck, she burst out in a sheet of flame ... Here, in this lonely bay, lay the fine ship ‘Fanchon’, and burnt to the water’s edge. Nothing could exceed the almost awful profoundness of the solitude ... a silence broken only by the roaring and crackling of the flames, as they wreathed and shot far upward, illuminating the midnight darkness.27

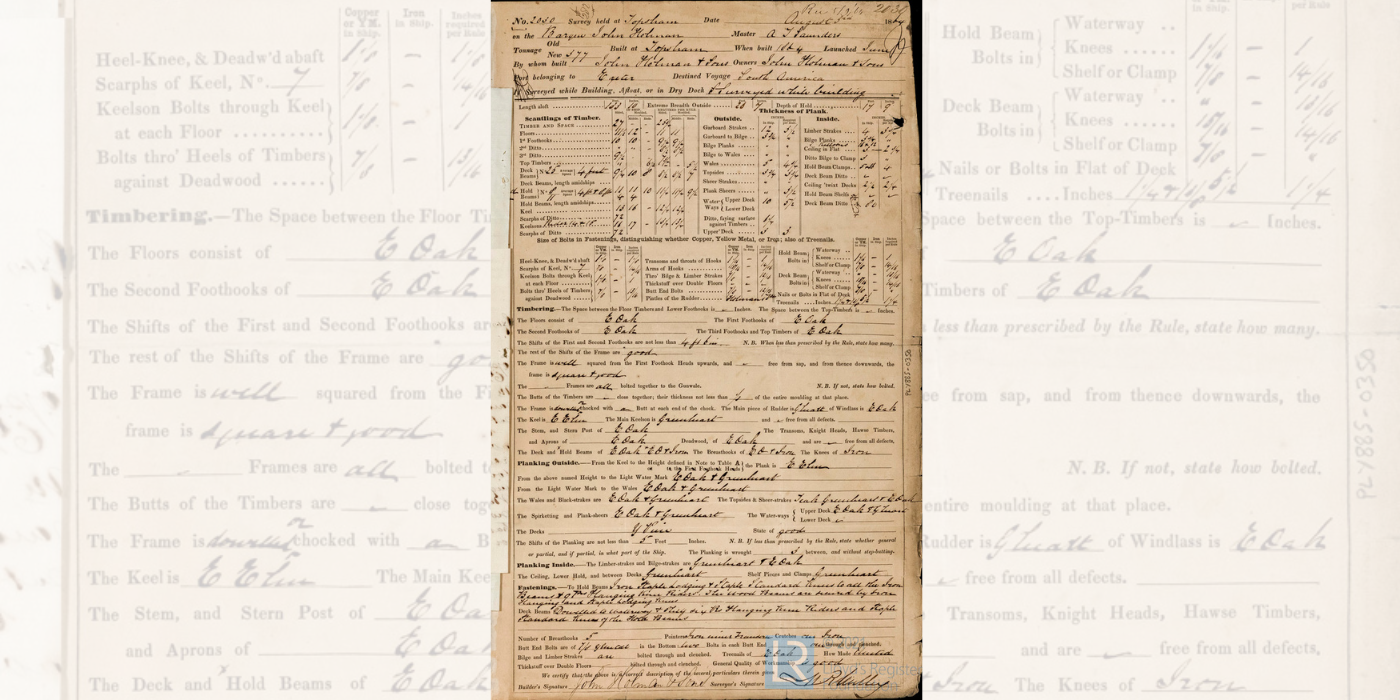

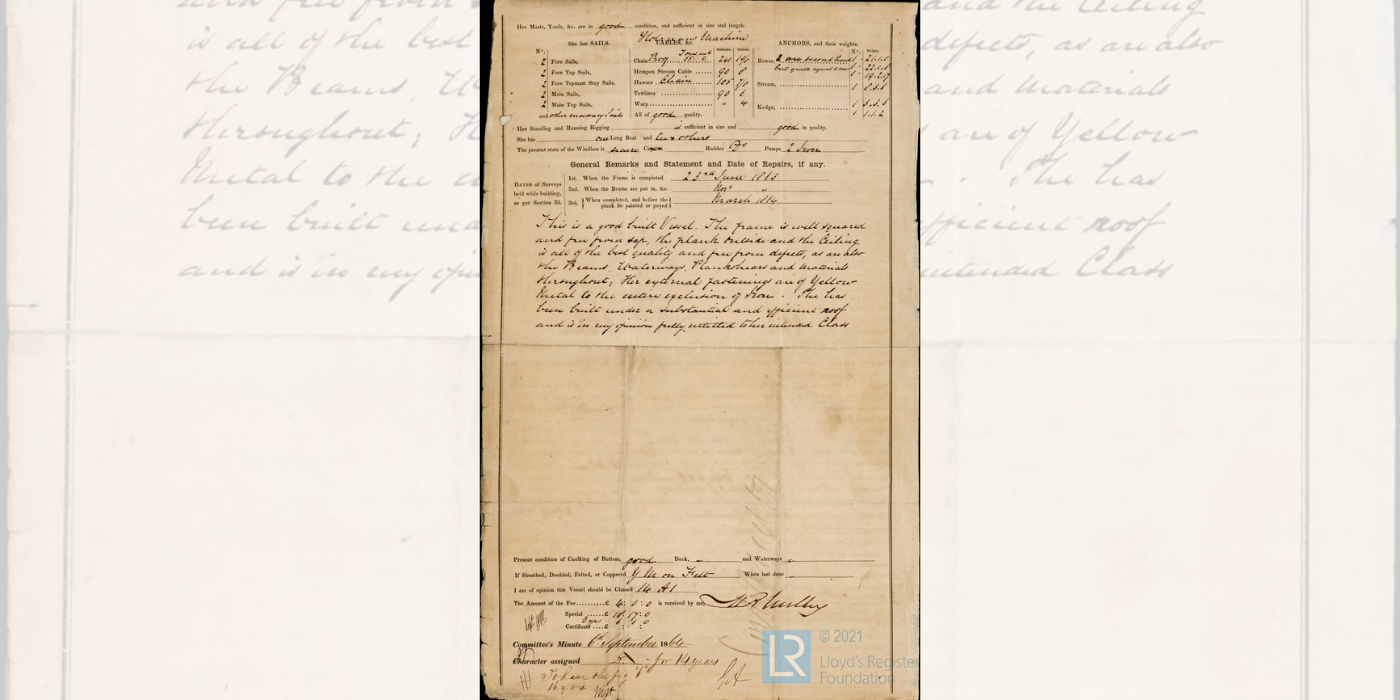

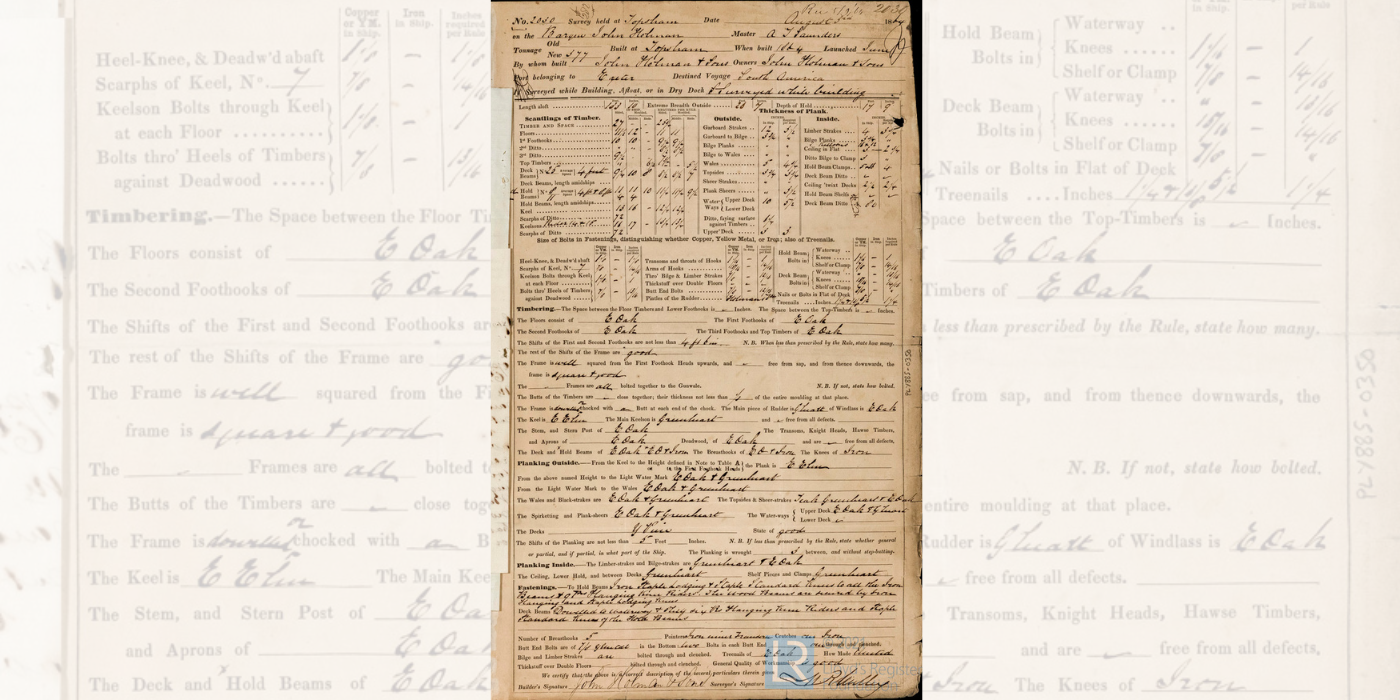

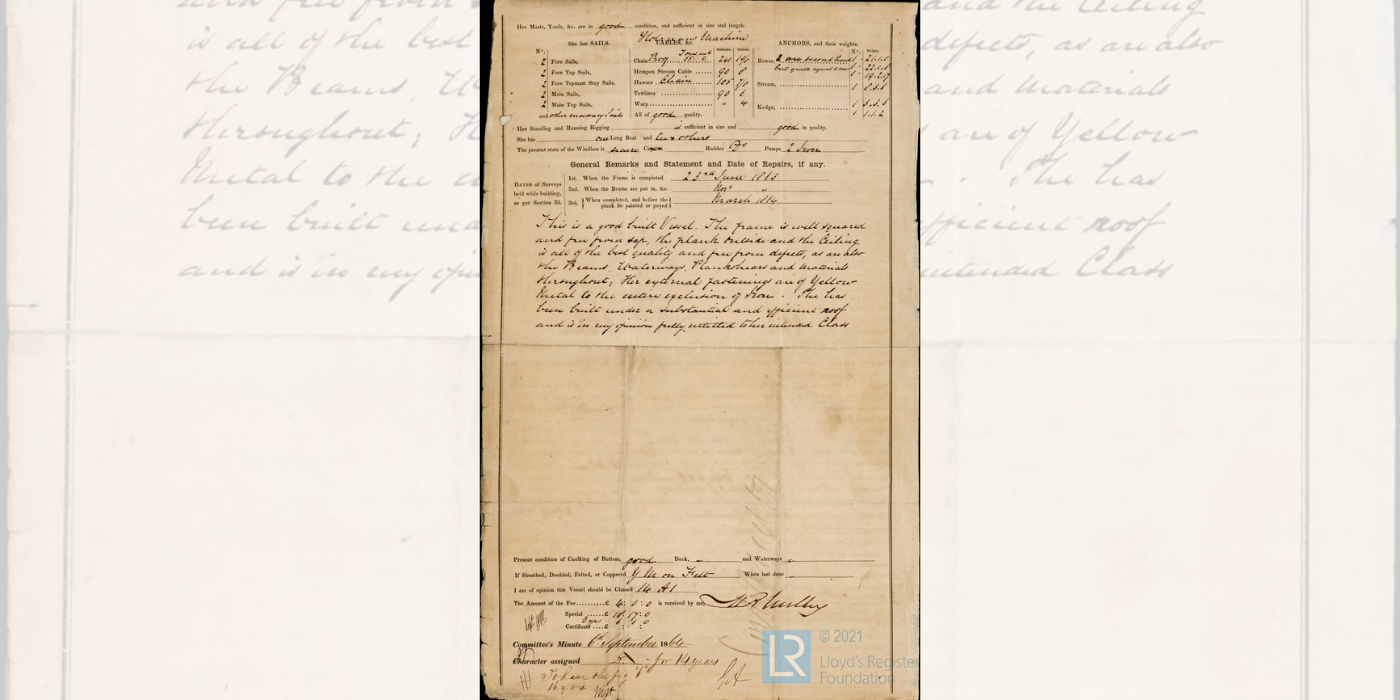

The John Holman’s coal cargo was on fire when last seen. A wooden barque of 377 tons, she was constructed in 1864 for John Holman & Sons under special survey at Topsham in Devon, with the Lloyd’s Register surveyor commenting: ‘This is a good built Vessel ... She has been built under a substantial and efficient roof and is in my opinion fully entitled to her intended Class’. That class was A1 for 14 years, and she was named after John Bagwell Holman, who had died the previous year and since 1839 had himself been a Lloyd’s Register surveyor at the port. The vessel lasted barely a year. 28 In September 1865 she was at Cape Horn with a cargo of South Wales coal, destined for Valparaiso. A passing vessel took a letter from her captain, Abraham T Saunders, warning that the cargo was on fire and they were hoping to reach the Falklands: ‘My mate and crew are sick with the gas of the coal today. I have hove overboard 20 tons or about and am afraid she is on fire. Awful on board. No one can stop below for gas ... She is fearful below.’ The ship was never seen again, and the master, twelve crew members and three apprentices were all lost. 29

Topsham, Devon, where the John Holman was built

Survey of the John Holman (front)

Survey of the John Holman (back)

Topsham, Devon, where the John Holman was built

Survey of the John Holman (front)

Survey of the John Holman (back)

Most fires aboard coal-laden vessels occurred about two months after leaving port. In a lengthy poem ‘With Coal to Callao’, first published in 1897, E J Brady imagines a ship laden with coal leaving Newcastle, New South Wales, destined for Callao, Peru:

They heaved her log for sixty days.

But on the sixty-first

Her greasy cargo went ablaze,

And then the hatches burst!

’Twas “Man the pumps! All hands to pumps;

and curse her as ye go;

A broken ship, a burning ship, ten days from

Callao!” 30

As the fire took hold, the crew’s efforts were in vain, and the ship sank with the loss of all hands, their fate forever unknown. ‘With Coal to Callao’ is a powerful memorial to so many coal-carrying ships that were simply ‘posted missing’ and soon forgotten.

Related Stories by the Lloyd's Register Foundation Heritage & Education Centre:

Coal at Sea: The Hazards of Cargoes, Bunkers, Loading, Unloading, Trimming and Shifting

A Burning Issue: Keeping Ships Safe From Fire

Guano: The Perilous Cargo of Flammable and Noxious Fertiliser

'What Harm Could One Do?' The Disastrous Result of Smoking at Sea

Other useful links:

Footnotes

-

1

Aberdeen Press & Journal 20 November 1753, p 1 (taken from the Edinburgh Courant of 13 November). In the Caledonian Mercury of 31 May 1753, pp 2–3, an advertisement for the Pearl invited passengers wanting to settle in Maryland to apply.

-

2

Report on Spontaneous Combustion of Coal in Ships 1866 (London: A Williams); Report of the Royal Commissioners appointed to inquire into the spontaneous combustion of coal in ships 1876 (London: HMSO); Final Report of the Royal Commission on Loss of Life at Sea 1887 (London: HMSO); Report of the Royal Commission appointed to inquire into the Dangers to which Vessels Carrying Coal are said to be peculiarly liable, and as to the best means that can be adopted for removing or lessening the same 1897 (Sydney, New South Wales); Thomas Rowan 1882 Coal: Spontaneous Combustion and Explosions occurring in coal cargoes: their treatment and prevention (London and New York: E and F N Spon); Michael Clark 2006 ‘“Bound Out for Callao!” The Pacific coal trade 1876 to 1896: Selling Coal or Selling Lives? Part I’ The Great Circle 28, pp 26–45; Michael Clark 2007 ‘“Bound Out for Callao!” The Pacific coal trade 1876 to 1896: Selling Coal or Selling Lives? Part II’ The Great Circle 29, pp 3–21; Tim Carter et al 2023 ‘Loss of life at sea from shipping British coal since 1890’ International Journal of Maritime History 35, pp 1–23.

-

3

Roy and Lesley Adkins 2021 When There Were Birds: The forgotten history of our connections (London: Little, Brown), pp 364–70. Carbon monoxide was the main killer in pits, but it was only at the end of the 19th century that canaries were found to be reliable indicators of that gas. See also Clark 2006, p 40, and Rowan 1882, pp 32–7, lii–liii.

-

4

See Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, from 1st July, 1878, to the 30th June, 1879 (London). According to the official Wreck Report, there were two ‘Richmond’ vessels from London, causing them confusion, but the one in question was owned by Messrs Dixon & Harris.

-

5

Walter Murton 1884 Wreck Inquiries: The Law and Practice relating to Formal Investigations in the United Kingdom, British Possessions and before Naval Courts into Shipping Casualties and the Incompetency and Misconduct of Ships’ Officers (London: Stevens & Sons; Pewtress & Co), p 248. The inspector was Thomas Errington Wales. See also the Wreck Report of the Court of Inquiry held at the Town Hall, Cardiff, 19–20 December 1878.

-

6

M Onifade and B Genc 2020 ‘A review of research on spontaneous combustion of coal’ International Journal of Mining Science and Technology 30, pp 303–11. See also David B Clement 2021 Square-Rigger Sunset: The Passages of Four and Five-Masted Ships and Barques volume 1 (Exeter: The South West Maritime History Society), pp 127–38.

-

7

See p 110 of T W Bunning 1875–6 ‘On the Prevention of Spontaneous Combustion of Coal at Sea’ Transactions of North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers 25, pp 107–40, 178–88; see also p 501 of Watson Smith 1919 ‘Spontaneous Combustion’ Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 67, pp 500–7.

-

8

Report on Spontaneous Combustion of Coal in Ships 1866, p 16. He was Captain James A Heathcote of the Indian Navy.

-

9

Report of the Royal Commissioners appointed to inquire into the spontaneous combustion of coal in ships 1876 (London: HMSO), p 80 of appendix to the report; Clark 2007; letter from Henry J Bath (1821–75) published in Report on Spontaneous Combustion of Coal in Ships 1866, pp 14–15, where his name is spelled as Barth. See also Mike Jackson 2010 Henry Bath & Son: A company and family history (https://www.henrybath.com/assets/downloads/Complete%20Henry%20Bath%20History.pdf).

-

10

The Monkshaven was built under special survey at Whitby in 1871 and was classed ✠16A1. See Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, from 1st July, 1876, to the 30th June, 1877 (London), and Lloyd’s List 25 July 1876, p 6, and 18 November 1876, p 10.

-

11

Mrs Brassey 1878 Around the World in the Yacht ‘Sunbeam’: our home on the ocean for eleven months (New York: Henry Holt and Company), pp 104–5, 108–9. She says (p 105) that the Monkshaven was 68 days out from Swansea (it was actually Porthcawl) and that the smelting coal was loaded at Sunderland, which is unlikely.

-

12

Brassey 1878, pp 105–6.

-

13

Brassey 1878, pp 106–7. She is often quoted as stating that 1 in 3 of all coal-laden vessels were destroyed by fire, but she actually meant ones carrying smelting coal.

-

14

The Leeds Times 19 April 1851, p 6; D B Bates 1857 Incidents on Land and Water, or Four Years on the Pacific Coast, being a narrative of the burning of the ships Nonantum, Humayoon and Fanchon, together with many startling and interesting adventures on sea and land (Boston: James French and Company), pp 12–23. Under American legislation, American vessels had to be used for the coastal trade of coal, even when a voyage round Cape Horn was involved. For American coal cargoes, see David B Clement 2021 Square-Rigger Sunset: The Passages of Four and Five-Masted Ships and Barques volume 1 (Exeter: The South West Maritime History Society), p 131.

-

15

Rowan 1882, p 19; Report of the Royal Commissioners appointed to inquire into the spontaneous combustion of coal in ships 1876 (London: HMSO), p 79 of appendix to the report.

-

16

Report of the Royal Commissioners appointed to inquire into the spontaneous combustion of coal in ships 1876 (London: HMSO), p 196 of minutes of the evidence.

-

17

Evidence given in February 1886 – see Final Report of the Royal Commission on Loss of Life at Sea 1887 (London: HMSO), p 15.

-

18

Report of the Royal Commissioners appointed to inquire into the spontaneous combustion of coal in ships 1876 (London: HMSO), p 79 of Appendix to the Report.

-

19

William H S Jones 1956 The Cape Horn Breed: My Experiences as an Apprentice in Sail in the Fullrigged Ship “British Isles” (London: Andrew Melrose), pp 54–5.

-

20

Jones 1956, p 51.

-

21

Joseph Conrad 1898 ‘Youth: A Narrative’ Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 164, pp 309–31. The Palestine was built in 1857. See Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, from 1st July, 1883, to the 30th June, 1884 (London). See also Lloyd’s List 26 April 1883, p 12.

-

22

Conrad 1898, p 318. See also Peter Villiers 2006 Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner (Rendlesham: Seafarer Books), pp 44–51; Liverpool Journal of Commerce 19 April 1883, p 3.

-

23

Bates 1857, pp 31–2; The Leeds Times 19 April 1851, p 6.

-

24

The Humayoon was constructed in 1842 and classed as A1 for 12 years. See Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, from 1st July, 1842, to the 30th June, 1843 (London)

-

25

Bates 1857, pp 47–57.

-

26

Bates 1857, pp 58–62; The Leeds Times 19 April 1851, p 6.

-

27

Bates 1857, p 65. The Fanchon reached Peru in mid-January 1851.

-

28

John Bagwell Holman senior lived 1800 to 1863. Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, from 1st July, 1865, to the 30th June, 1866 (London). For the Lloyd’s Register survey report, see: https://hec.lrfoundation.org.uk/archive-library/documents/lrf-pun-ply885-0350-r/search/everywhere:holman/page/1

-

29

David B Clement 2005 Holman’s: A Family Business of Shipbuilders, Shipowners and Insurers from 1832 (Topsham Museum Society), pp 100–2. The captain’s letter was dated 30 September 1865.

-

30

The Bulletin (Sydney) 31 July 1897, p 28. Some sources incorrectly give 50 rather than 60 days, including Stan Hugill 1967 Sailortown (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; New York: E P Dutton & Co), p 262 (even though he cites Brady as the source).