In the early morning of the 29th of May 1914, the RMS Empress of Ireland was cruising on the St. Lawrence River, having left Quebec City the previous afternoon, and making her way towards Liverpool. This comfortable ocean liner was on the return trip of her 96th transatlantic voyage, pride of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company. The Empress of Ireland was proceeding at full speed, when the captain, Henry George Kendall, sighted the collier Storstad approaching in the opposite direction, roughly two miles down the river 1. In that moment, a fog bank crept on the water between the two vessels, impairing the vessels’ navigation lights visibility. Captain Kendall called for the engines to go full speed astern 2 and stopped the ship. Steam whistles were blown from each ship to signal the last manoeuvre. Nevertheless, the Storstad ominously reappeared minutes later, on a course that would inevitably cause a collision with the Empress. Despite the efforts of both vessels, the Empress was rammed amidship to stern, which caused catastrophic damage when several water-tight compartments were breached. The Empress of Ireland sank in less than 15 minutes, causing the death of 1,012 people, in the worst Canadian maritime disaster to that time.

Despite the sheer number of human casualties, which at the time of the incident was only comparable to the sinking of the RMS Titanic, the story of the Empress of Ireland is currently little known outside the circle of maritime academics and enthusiasts. Nonetheless, much can be unearthed on this event, as well as countless others, exploring a variety of archival resources. The Heritage and Education Centre holds long standing ties to historical institutions and maritime collections, a synergy enhancing research opportunities through a range of accessible documents from ship plans and survey reports to voyages accounts and crew lists.

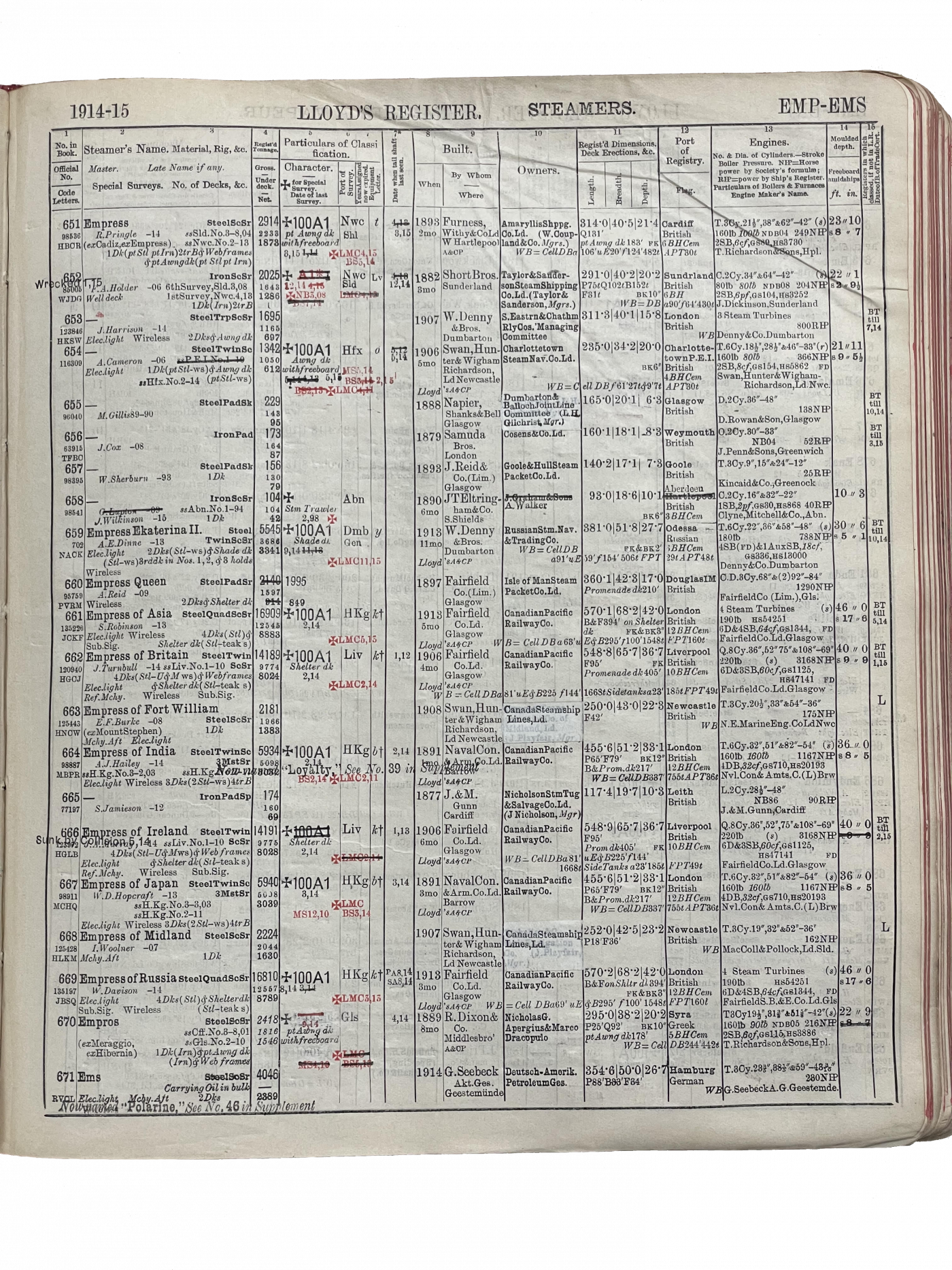

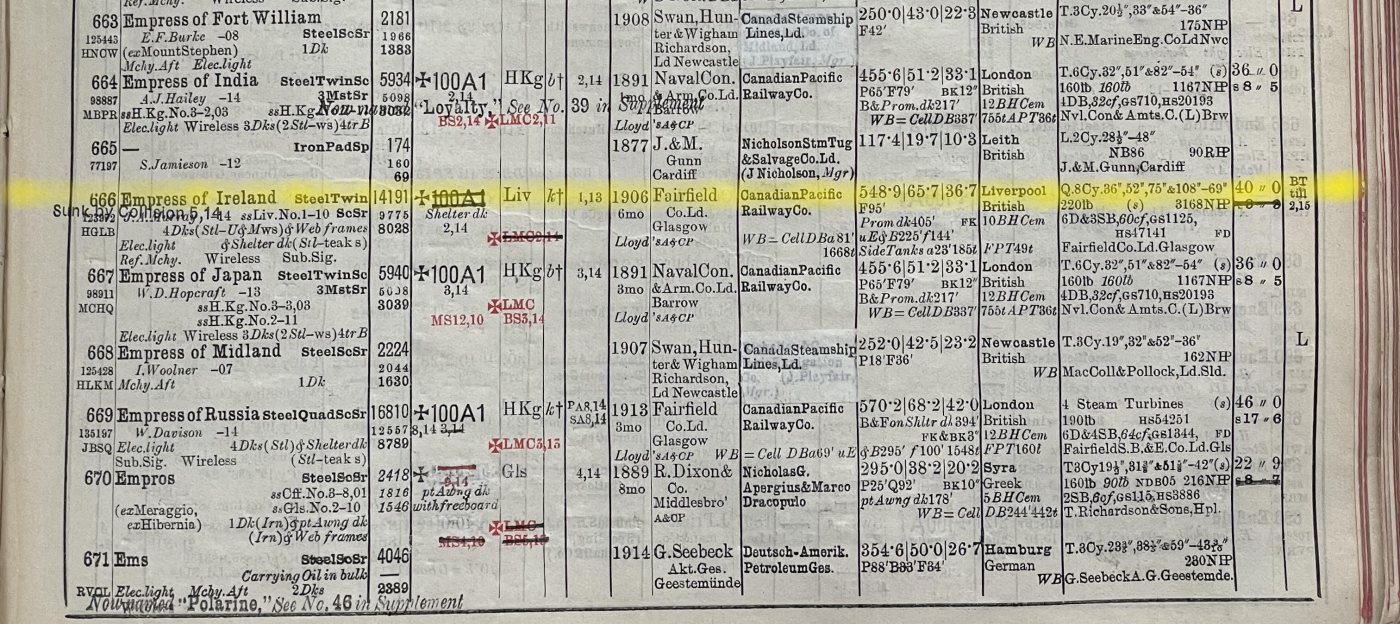

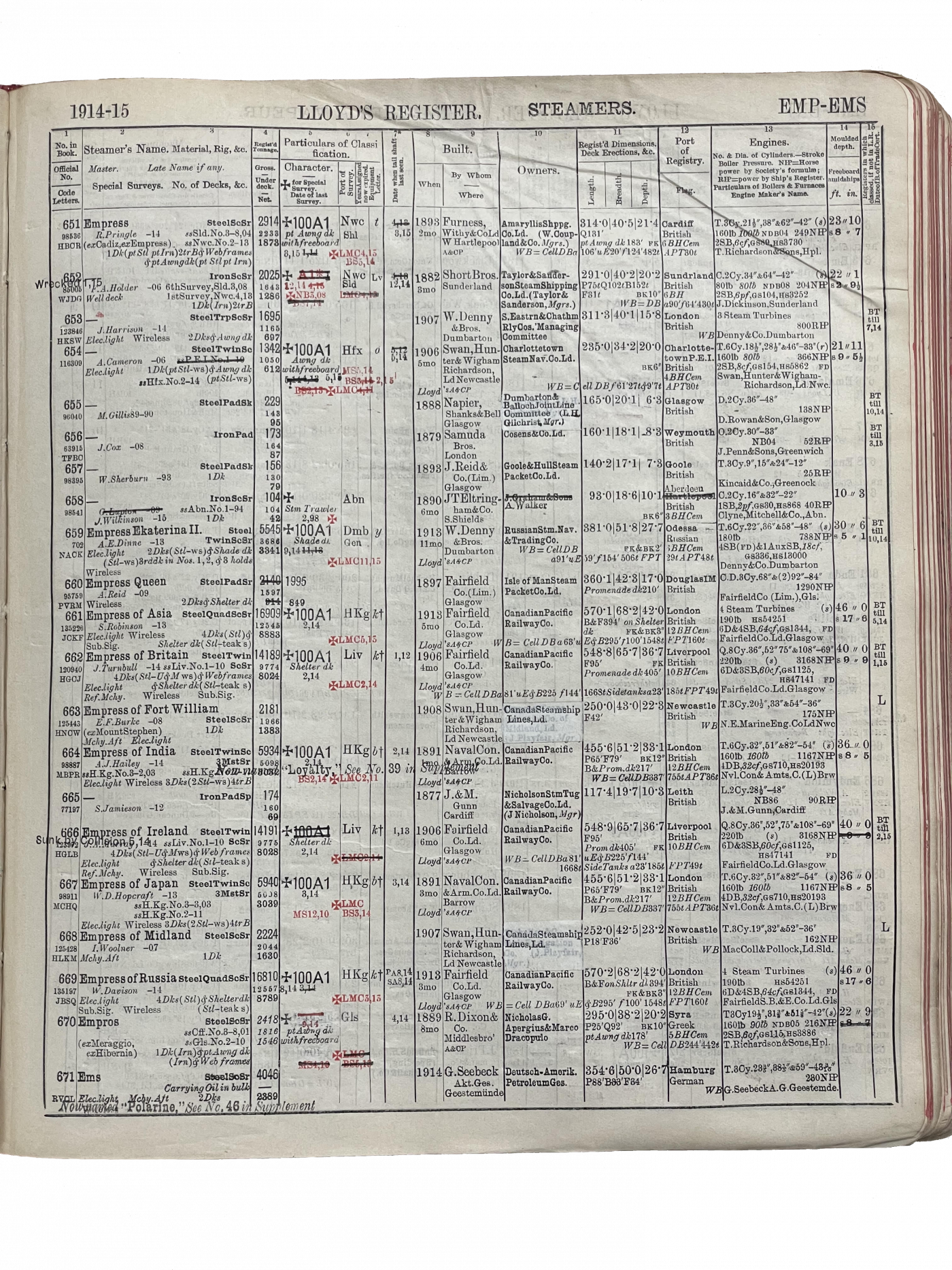

Entry for Empress of Ireland

RMS Empress of Ireland Entry

Entry for Empress of Ireland

RMS Empress of Ireland Entry

By the early 20th Century, the largest, fastest, and most luxurious ships were being designed and engineered to ease the difficulties of a voyage on some of the most treacherous waters on Earth. Connecting Britain and mainland Europe to North America, where the nascent United States superpower and the Dominion of Canada were attracting the hopes of countless migrants, was a necessity. 60 years of progress in marine engineering, essentially driven by the profits of ferrying people and cargo from one side of the Atlantic to the other, culminated with the development of the ocean-going passenger liners 3 . During this period, ships had gone through major changes, from construction material, where they shifted from wood to iron and ultimately steel, to propulsion, where the early fully rigged paddle-steamers had given way to increasingly larger vessels counting on the power of their steam turbine engines only. Experiencing the Atlantic crossing was not gambling with life anymore.

The Empress of Ireland was one of a series of ocean-going steamships owned by Canadian Pacific Railway Co., all of which bore the prefix 'Empress'. She and her sistership Empress of Britain were purposely built for transatlantic express voyages between the United Kingdom and Canada. They were easily the largest steamers in the Canadian trade and soon proved themselves to be the fastest. Both vessels were propelled by quadruple-expansion steam engines with a top speed in excess of 20 knots. The Empress of Britain was the first of the class and was launched in November 1905, leaving Liverpool in the Spring of 1906 on her maiden voyage to Quebec. She made newspaper headlines on her second voyage crossing the Atlantic in five days and managed to survive the First World War despite being employed by the Royal Navy for patrolling, troop transport, and as an armed merchant cruiser 4. As a peculiar coincidence, the Empress of Britain was involved in an incident with the sistership of the Storstad in July 1912, when she ran into and sank the collier Helvetia in the St. Lawrence River, near the same spot of the Empress of Ireland incident 5.

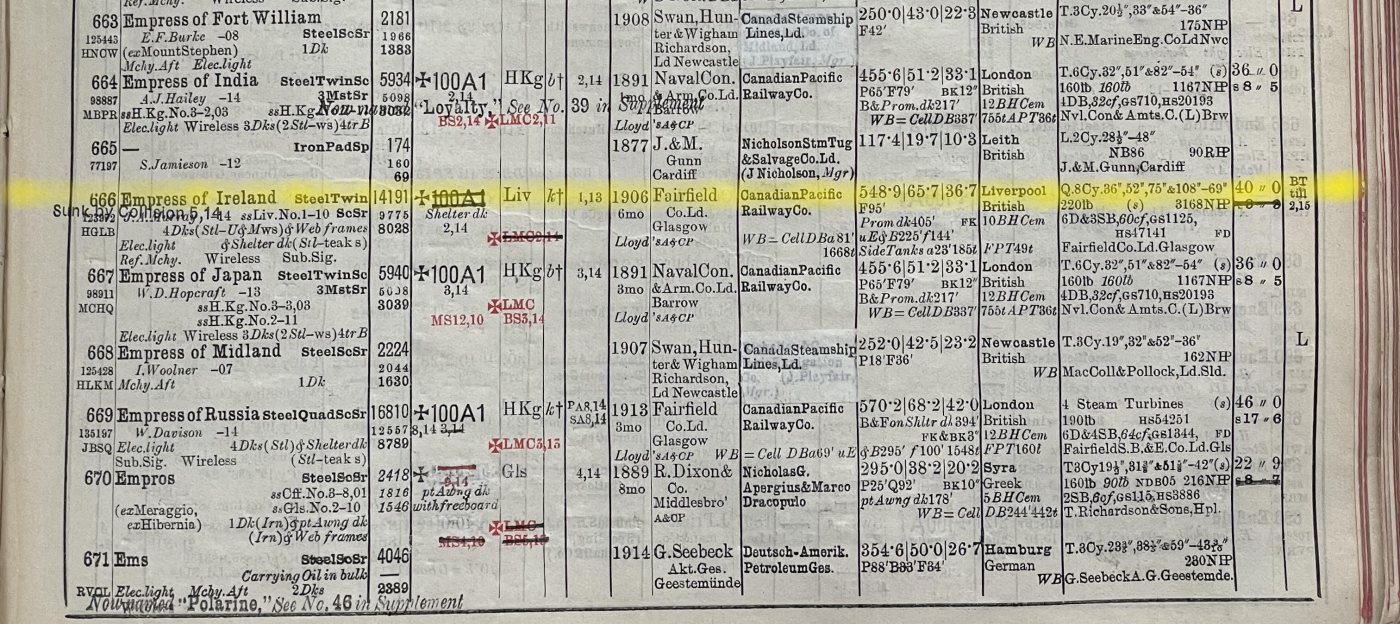

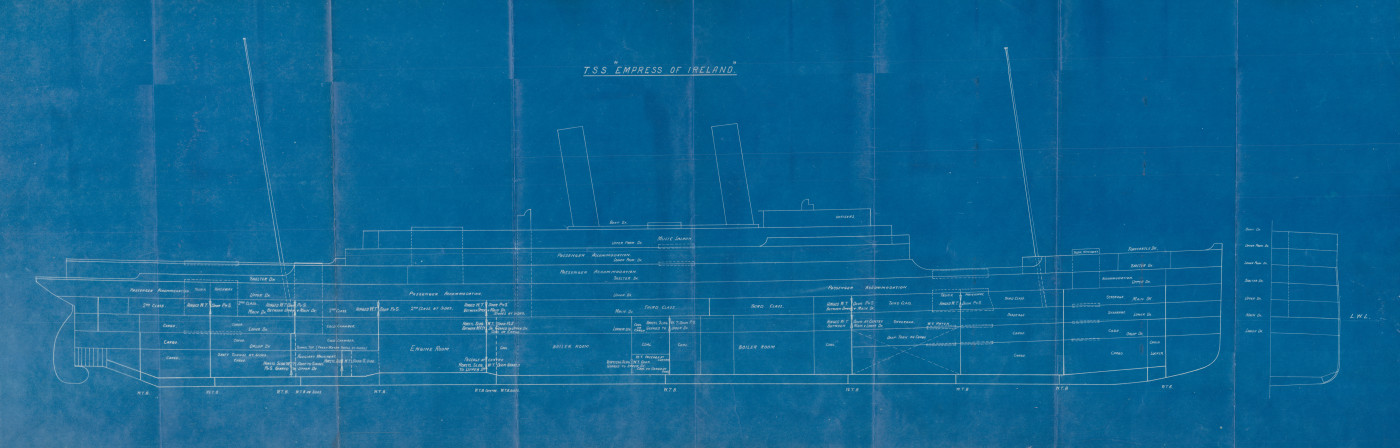

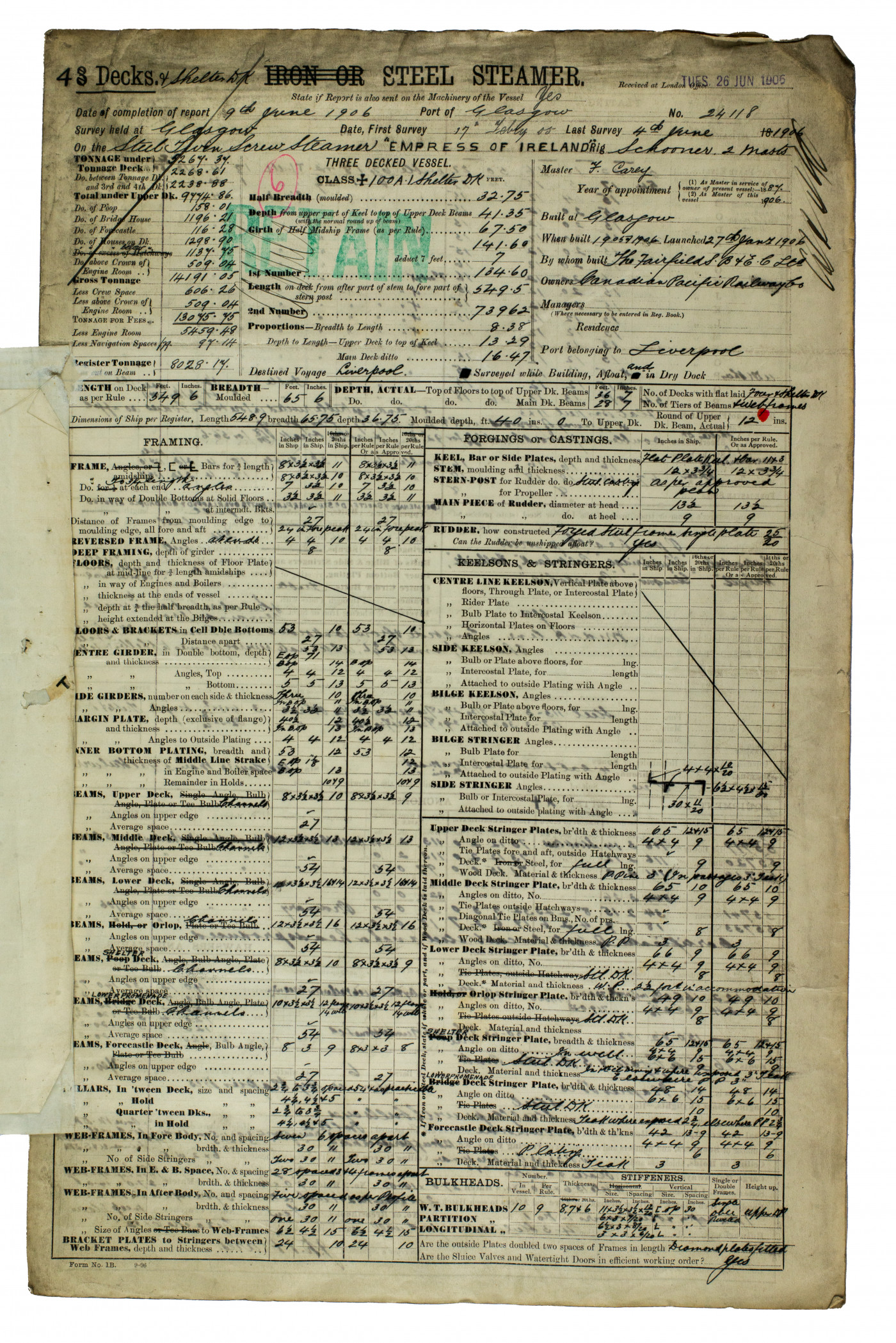

The Empress of Ireland was built in 1906 by Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Co. Ltd. in the company yard on the River Clyde at Govan, a district of Glasgow. She was a steel twin screw schooner rigged steamer 548.9' long, 65.7' broad, and 36.7' deep, with a gross tonnage of 14191 and a net tonnage of 8028. Canadian Pacific Railway Co. commissioned Lloyd’s Register of Shipping (LR) to undertake plan approval and special survey during construction of the steel steamship, with a view to the vessel being classed by LR. Arthur L. Jones, one of the 13 engineer surveyors stationed in the Glasgow district, reported on the surveys during construction of her machinery and electric lighting. She was launched by Mrs. Gracie, the wife of Fairfield’s managing director, on the 27th of January 1906 6 .

The Empress was then registered under the British flag in the port of Liverpool on June 7th, as attested by the Appropriation Book of the Registrar General of Shipping and Seamen, which also provided her with the official number 123972. On the same date, the Registrar General of Shipping and Seamen sent their form G. R. 130, Vessels of 100 tons and Upwards to Lloyd’s Register, detailing the British flag registry details of the vessel, including the name and certificate number of her first Master, Frank Carey, where she was registered, her registered owner and details of number of shares held, constructional details and lengths, details of the machinery and particulars of her tonnage with calculations for the same on the reverse. On June 9th the ship surveyor J. D. Mares submitted his First Entry report for the vessel, detailing the construction of the vessel and the results of the 92 visits made to the vessel while under construction. The reports were submitted to the Glasgow Classification Committee who assigned Empress the classification notation | 100A1 Shelter deck, |LMC. The full details of Empress of Ireland were recorded in the Supplement to the 1906-07 Register Book, and in the main body of the book from 1907.

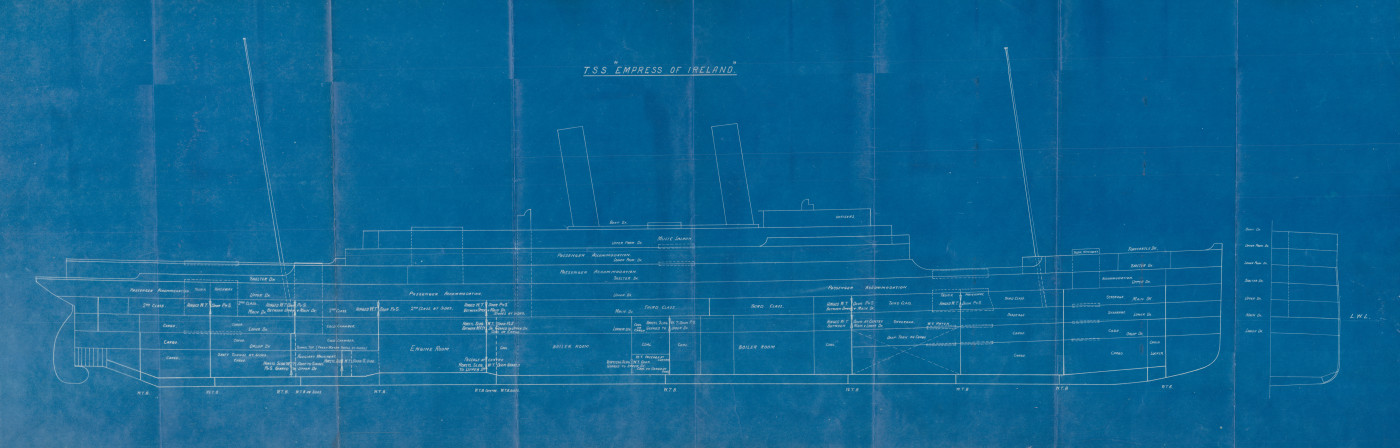

Profile plan of Empress of Ireland

Front page of First Entry Steel Steamer Report for Empress of Ireland, 9th June 1906

Profile plan of Empress of Ireland

Front page of First Entry Steel Steamer Report for Empress of Ireland, 9th June 1906

The Empress and her sistership were the biggest ships built by Fairfield until then and had been scrutinised and inspected by Lloyd’s Register throughout construction. At maximum capacity, the Empress of Ireland could host 1550 passengers: 300 cruising in first class, 450 in second class, and 800 in third class. Despite not being ostentatiously luxurious such as other vessels of her time, the Empress held an unchallenged reputation. With her regular transatlantic service, she served on the early 20th Century migration routes, along which hundreds of thousands of emigrants travelled to take their chance in North America. These passengers would travel in third class and constitute the majority of ticket holders. Years of continuous high request for Atlantic crossings forced the fare price down, allowing passengers to travel to Canada for £6 and 10 shillings (roughly equivalent to £800 in 2022), while the conditions on board radically improved from previous decades 7.

The Empress of Ireland left Liverpool on her maiden voyage to Quebec on the 29th of June 1906 and in subsequent voyages secured a reputation for fast runs across the Atlantic. During the winter months, when the St. Lawrence River would freeze, the Empress travelled to and from Halifax, Nova Scotia. She continued sailing on the U.K. - Canada route until May 1914 when she was sunk. On her last voyage, she embarked with passengers hailing from across North America and beyond, including New Zealand, Hong Kong, Japan and Fiji 8.

Among the crew members, there were two wireless operators. Following the Titanic incident in 1912, and the chief role of wireless in requesting immediate help and providing the exact location of the sinking vessel, wireless ship communications had become a requirement for passenger ships embarking with more than fifty passengers. The Marconi School of Wireless would train new operators, which at that time were in high demand and rapidly employed. On the Empress, the operators would alternate work shifts of six hours to six hours of rest. The swiftness of the operator’s reaction in sending the S.O.S. on the night of the incident helped significantly in reducing the loss of human life.

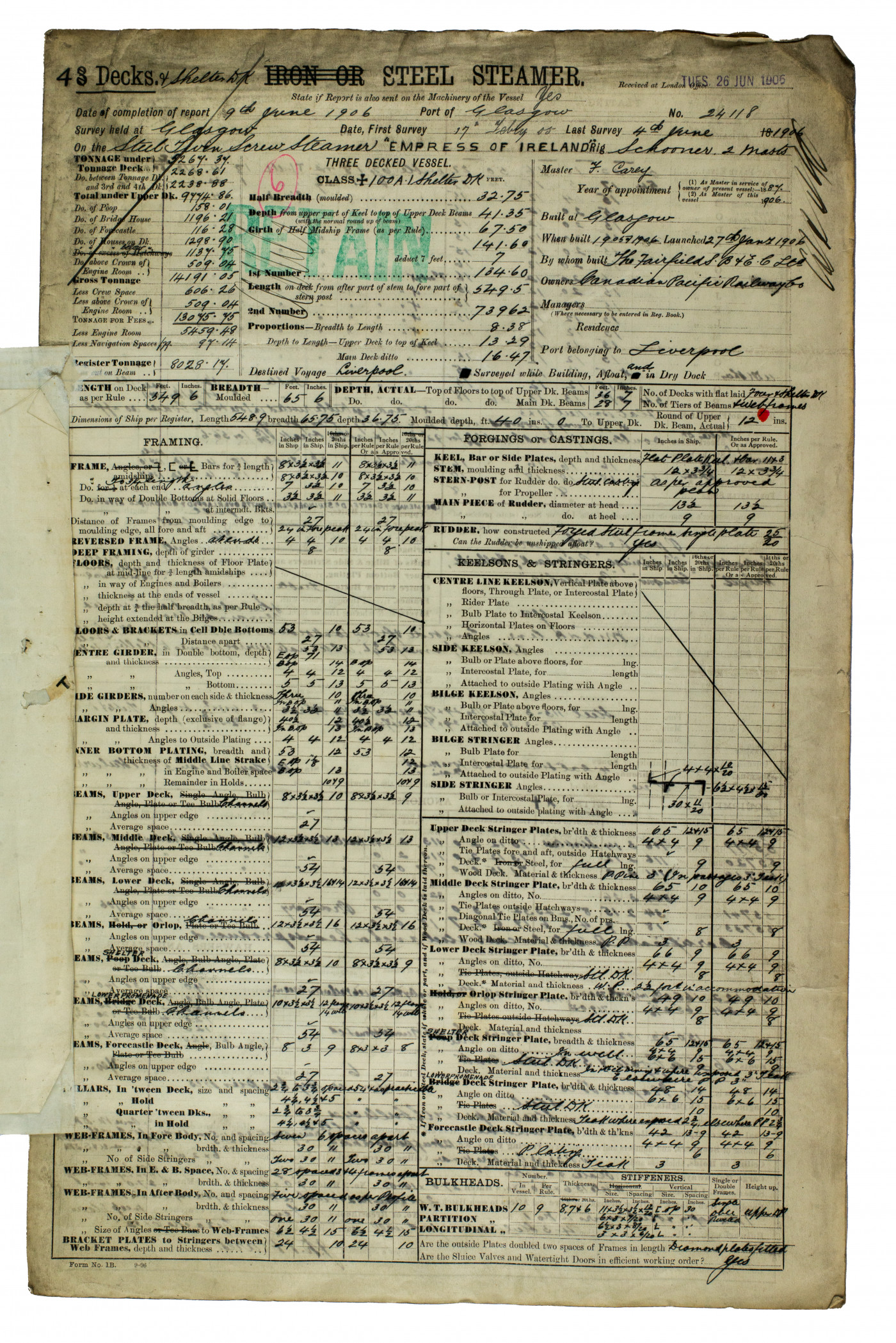

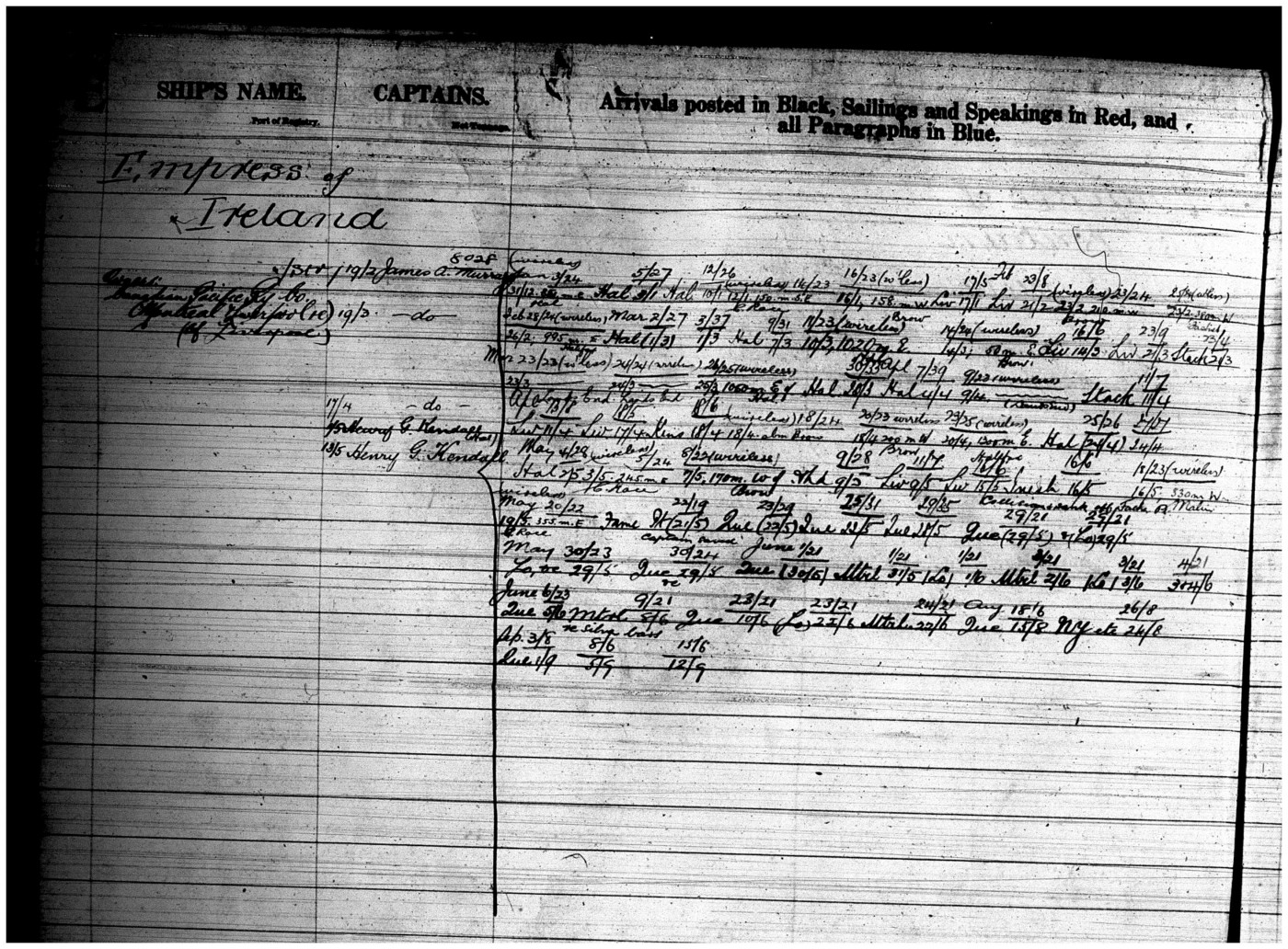

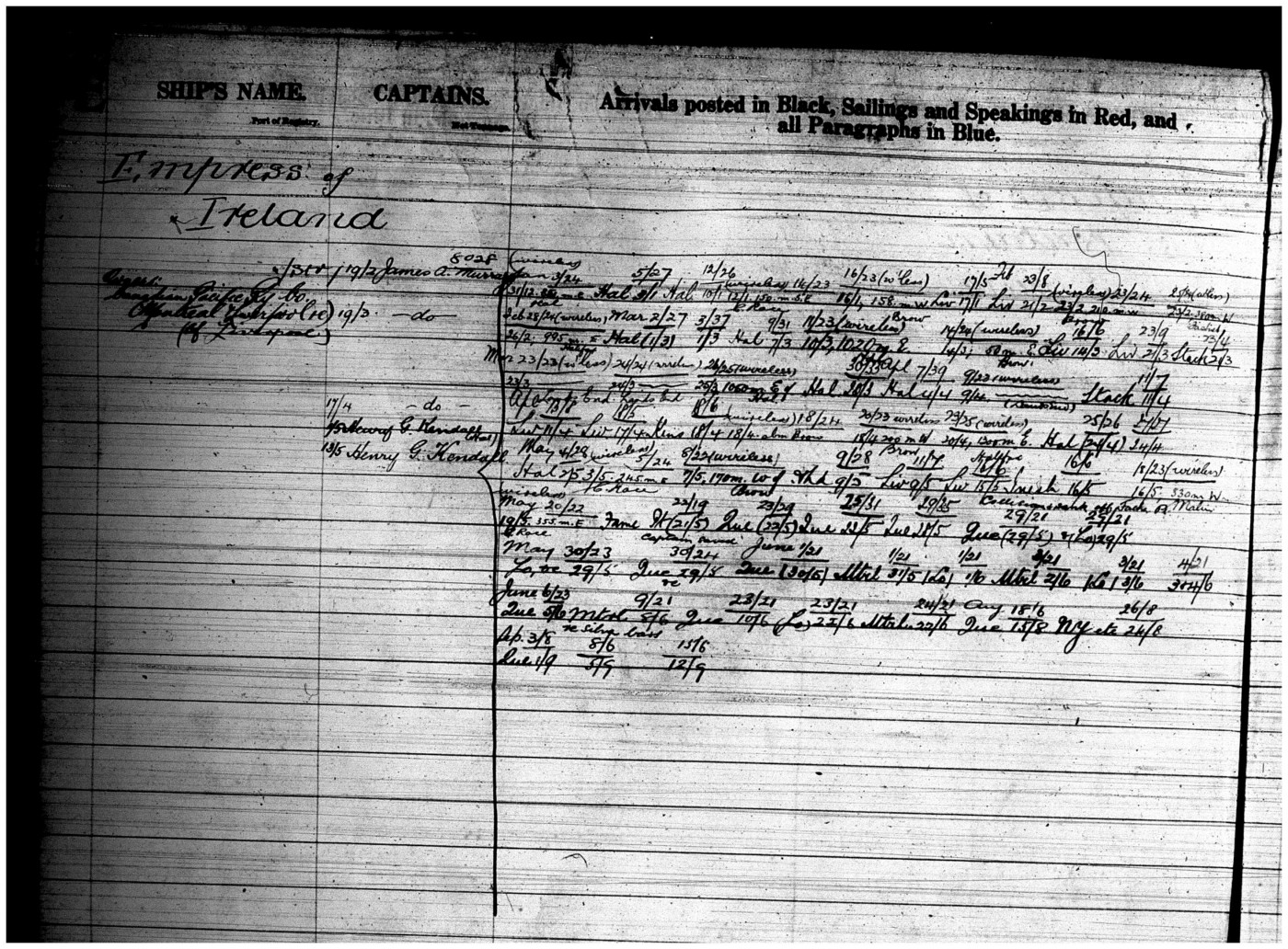

Empress of Ireland entry of the 1914 Index to Lloyd’s List

Incident Map

Empress of Ireland entry of the 1914 Index to Lloyd’s List

Incident Map

As often happened, the incident occurred at night. Dr James F. Grant, the liner’s surgeon, was one of the first people to reach safety and reported that the Storstad collided with the Empress at 1:52am. A first SOS message was sent by Ronald Ferguson, the chief wireless operator, to Quebec City, informing of the precarious state of the Empress, however the vessel violently lurched soon after, scattering all the telegraphic gear from tables and cupboards and preventing further communication. Captain Kendall later claimed that the Storstad made a subsequent mistake backing away from the liner, however the collier’s captain, Thomas Andersen, challenged this version of the facts, reporting that his ship maintained the position, but the Empress slipped away bending the Storstad’s bow. In any case, the ruptured hull of the Empress exposed her internal spaces, causing the liner to take on great quantities of water forcing her to list on her starboard side.

The vessel was equipped with watertight bulkheads to prevent water spreading to the adjacent compartments however the Empress was hit amidships, the most vulnerable area that could not be adequately subdivided. Despite concerted attempts, the crew were not able to close all the watertight bulkheads, which had to be operated manually 9, and more water kept flowing in. Not capable to withstand the extensive damage, and ingress of water, the engines and electric lighting failed shortly afterwards, adding darkness to the already nightmarish conditions on board.

The heavy list and the rapid sinking impaired the crew’s effectiveness in coordinating the emergency procedures. Of the sixteen steel lifeboats ready on the radial davits, only five on the starboard side were properly launched, while an undetermined number 10 of them were overturned. Crew attempting to launch the lifeboats on the port side, including the ship’s chief officer, were crushed on the railings by the severe list. The vast majority of the passengers were sleeping at the time of the collision, and few reached the main deck before the ship listed, even less managing to embark on the lifeboats or receive lifebelts before being forced into the icy water. The situation in the lower decks was more desperate, as many passengers on the starboard side of the liner did not even have the chance to leave their berths. Others were luckier and escaped the Empress through the portholes on the port side, one of these people being the ship’s surgeon.

The smaller crew of Storstad, composed of 36 men, joined the rescue operations launching three lifeboats and a small gig, additionally manning one of the liner’s boats once they reached the sinking Empress. These were rapidly filled with no hope to return to the wreck in time, given that the incident happened 4 miles off the riverbank. The Government steamships Eureka and Lady Evelyn were sent from Father Point, making haste to the scene of the disaster, but the Empress of Ireland had already sunk. Ferguson, the wireless operator, was able to reach the Lady Evelyn, from which he took over the equipment on board and kept reporting on the incident 11. The final number of lost lives varies slightly in the early records, although it is believed that 840 passengers and 172 crew perished that morning. The remaining 463 landed at Rimouski, where they could be attended by the locals. The complete passenger list is now held at the Musée de la Mer in Rimouski.

As well as carrying passengers, the Empress of Ireland contained 163 silver bullion bars 12. Their total value in 1914 amounted to $1.1 million ($30.5-31 million in 2022). Given the relatively shallow waters where the Empress sank, several attempts at locating the bar were undertaken throughout the summer of 1914. By September 12th, the divers had recovered the entirety of the lost silver, along with mail and valuable items belonging to passengers stored in the ship’s safe 13. Several items salvaged from the wreck at a later stage are now preserved in the Musée Maritime du Québec at L'Islet.

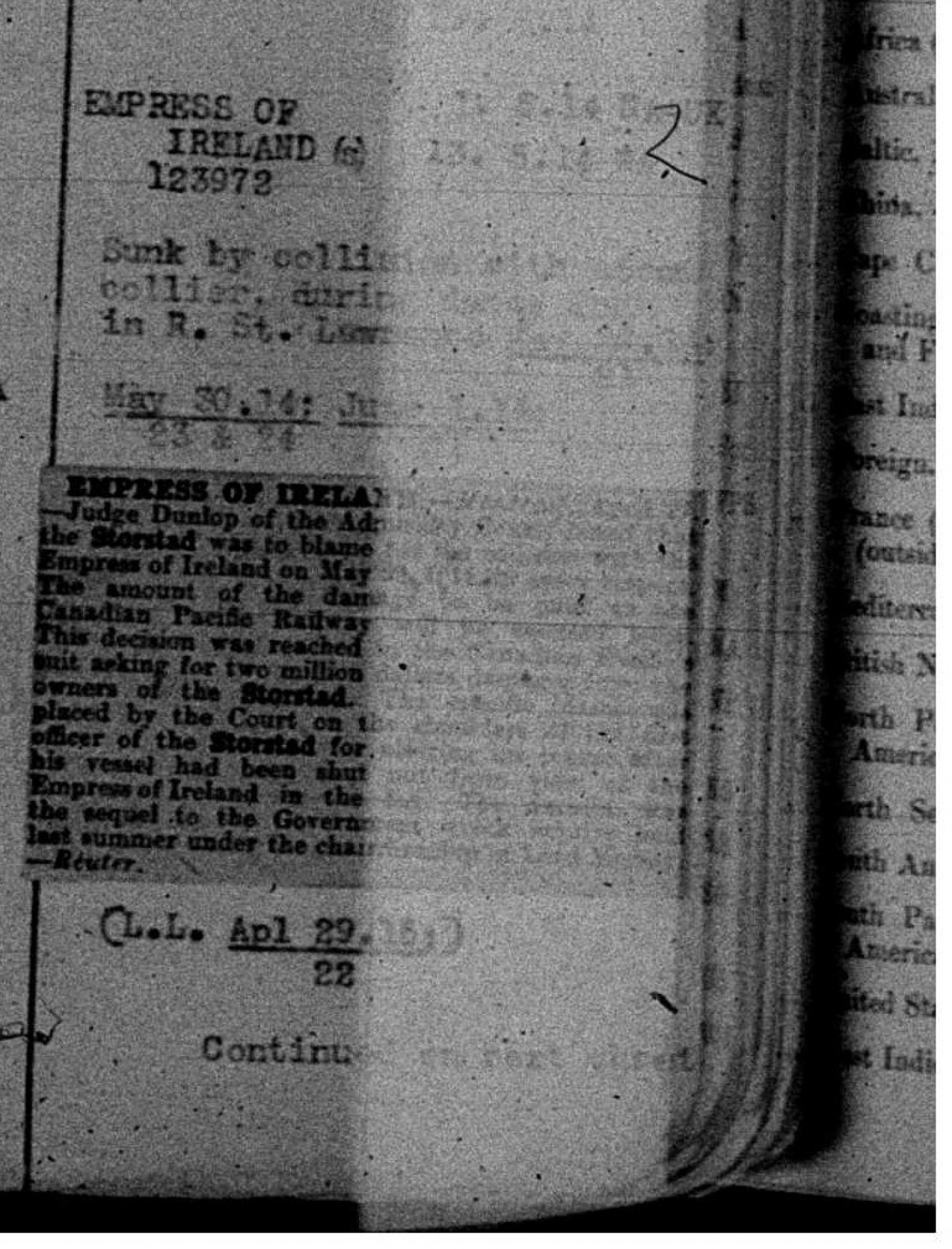

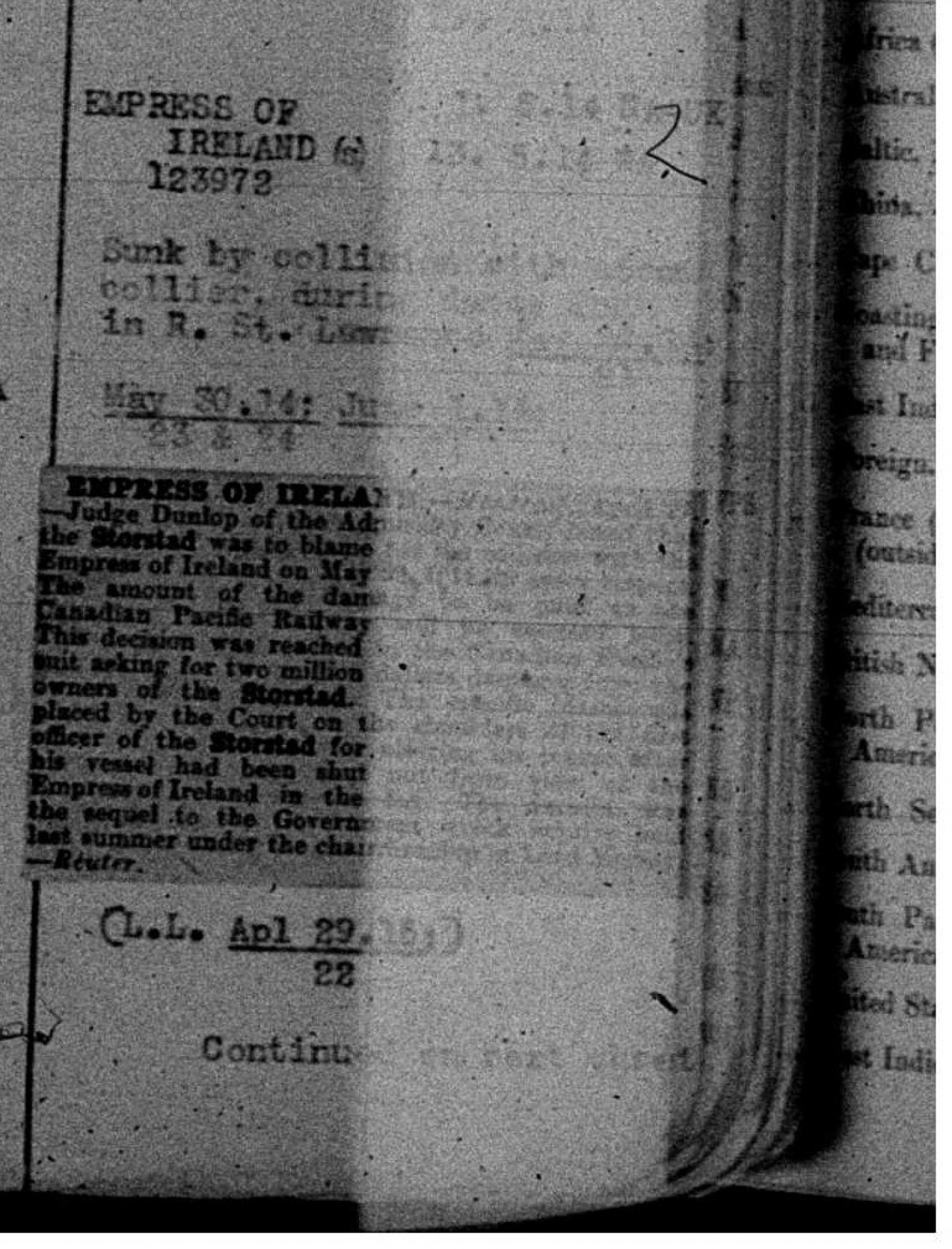

The Empress of Ireland incident occurred only two years after the RMS Titanic sank on the 15th of April 1912, following her collision with an iceberg. It sparked a renewed discussion on safety at sea, especially regarding the operation of lifeboats and manoeuvring with reduced visibility 14. Similarly to the Titanic, an official enquiry was launched into the loss of the Empress of Ireland. A copy of this enquiry is held at the National Archives in Kew. The hearings concluded that the Storstad was to be held accountable for the disaster as the First Officer Toftenes changed her course “because of current” to maintain stability but in fact ported the helm and brought the collision about 15. Additionally, First Officer Toftenes was found negligent of not having summoned Captain Andersen despite his request to be called should any course alteration be required. By the time he was finally on deck, it was too late.

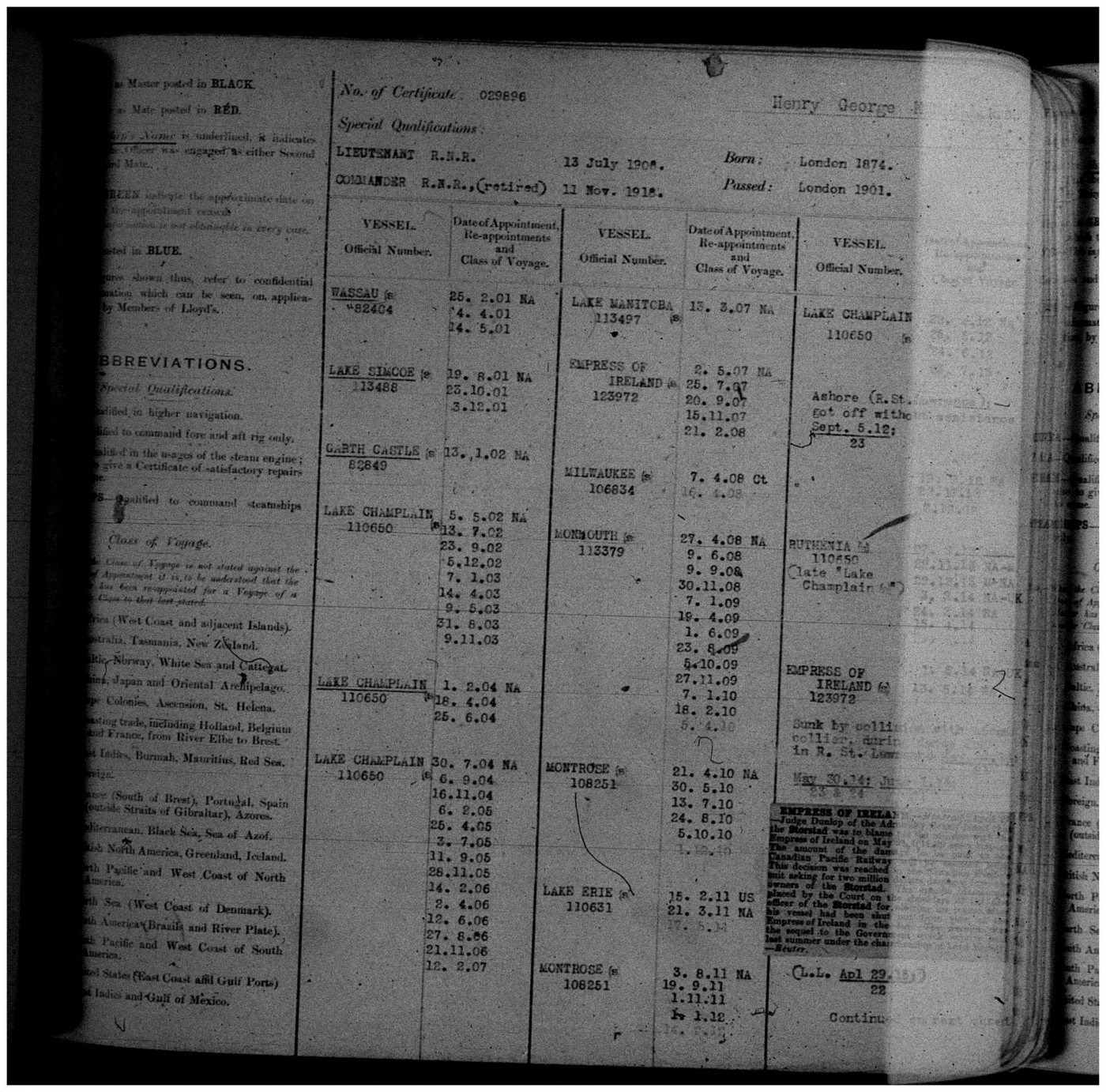

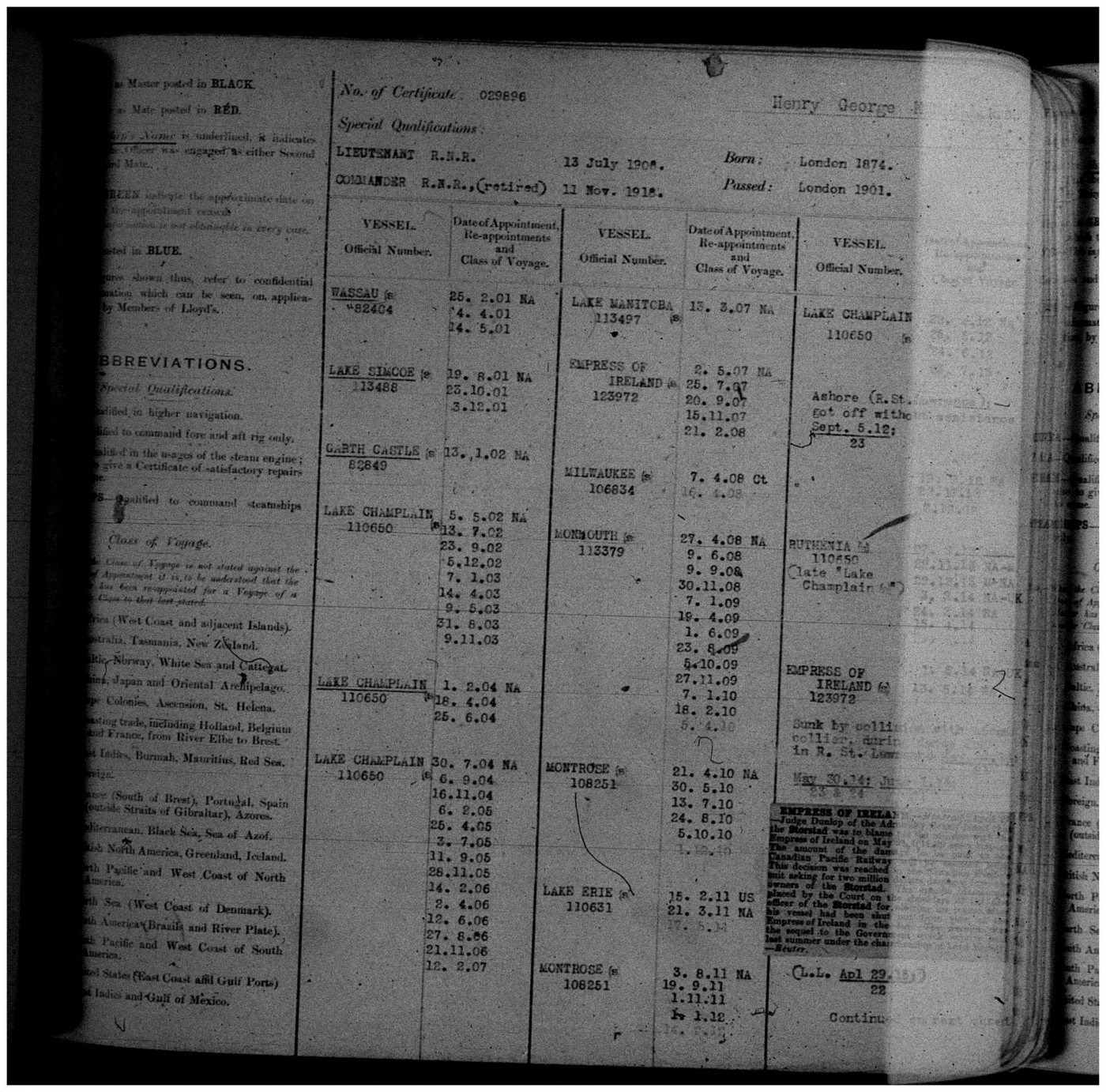

At the time of the Empress of Ireland's sinking in May 1914, Captain Kendall, R. N. R.16, had more than 11 years of service, all spent at Canadian Pacific. Moreover, it was not the first time he had made newspaper headlines. During his captaincy on the Montrose in 1910, he had contributed to the identification and capture of a notorious murderer, the dentist Harvey Crippen who had killed his wife and was travelling in disguise on board of the ship 17. He remained in service during the First World War and was mentioned in despatches in the London Gazette 18 for services rendered in patrol cruisers in 1917.

Detailed information on ships and voyages where Captain Kendall served can be found in the Lloyd’s Captains Register. This is a manuscript resource held at the London Metropolitan archives, also available at the Guildhall Library in microfilm. Kendall’s Master Certificate 19, dating from 1901 when he was 27 years old, is stored at the Caird Library and Archive in Greenwich.

Lloyd’s Captains Register entry for Henry G. Kendall (on microfilm).

Empress of Ireland and Henry G Kendall

Lloyd’s Captains Register entry for Henry G. Kendall (on microfilm).

Empress of Ireland and Henry G Kendall

Starting from a simple search of the latest entry for the Empress on the 1914 Register Book, a voyage has been undertaken across collections and archives uncovering the fate of people and assets. The Register Book states the withdrawal of the Empress from class in May 1914. Where a casualty is found on the Register Books, more information can be retrieved from the Casualty Returns, including the exact date, voyage, and circumstances of the incident.

Pairing Lloyd’s List to the above-mentioned resources it is possible to accurately track ships voyages, including dates of arrival and departure. Moreover, Lloyd’s List contains references to newspaper articles, radio extracts, and other media sources available when a casualty occurred. The reports published would usually shed light on specific locations and people involved, human loss, and cargo. For incidents causing sensation such as the Empress of Ireland’s, there would be detailed accounts following the case for weeks. Lloyd’s List entries have been summarised and grouped by ship in the Index to Lloyd’s List until 1927, when this resource was substituted by the Voyage Record Cards, compiled until 1975. Lloyd’s List, Index to Lloyd’s List, and the Voyage Records Cards are held at the Guildhall Library in London.

Consulting Lloyd’s List and the annexed Shipping Gazette, integrating the information retrieved to Lloyd’s Register resources has proven to be an effective way to trace the history of the Empress of Ireland. Replicating the same methodology, the histories of numerous other vessels can be uncovered, benefiting researchers and enthusiasts.

Footnotes

-

1

Shipping Gazette, 1st June 1914

-

2

Reserve the engines

-

3

Coleman, T. (1976), The Liners

-

4

Musk, G. (1989), Canadian Pacific: the story of the famous shipping line

-

5

Shipping Gazette, 30th May 1914; Casualty Returns, 1912

-

6

Musk, 1989

-

7

Croall, J. (1978), Fourteen minutes: The last voyage of the Empress of Ireland

-

8

Croall, 1978

-

9

Croall, 1978; Hocking, C. (1969), Dictionary of Disasters at Sea during the age of steam

-

10

Due to contrasting reports

-

11

Croall, 1978

-

12

Shipping Gazette, 1st June 1914

-

13

Lloyd’s List, 15th September 1914

-

14

Shipping Gazette, 30th June 1914

-

15

Toftenes wrongly assumed that the two vessels would pass each other port to port

-

16

Royal Navy Reserve

-

17

Croall, 1978

-

18

London Gazette, 21st June 1918

-

19

Certificate No. 029896.