Sailors once thought that bad luck was inevitable with any woman on board, and it was therefore easy to blame them for a run of misfortune. In reality, across the world and in different cultures, the relationship between women, the sea and ships was always varied and often contradictory. The history of seafaring cannot be understood without recognising this complex situation, because in the past the notion of safety encompassed custom and superstition rather than today’s values of science and technology.

Women on board merchant ships in the 19th century were generally the wives of captains, living apart from the crew, sometimes with their children. This was in contrast to the Royal Navy, which unofficially tolerated wives and mistresses across all ranks. Naval crews were considerably larger, as the ships were fighting machines, not cargo carriers, and so a few women could be more easily accommodated. 1 When in 1911 Captain J Lines became the new master of the barque Inversnaid, Thomas Fairburn also joined the crew as an apprentice. ‘When we heard that he was taking his wife on board for the voyage,’ Fairburn said, ‘the older hands did not approve and thought that a sailing ship was no place for an elderly female.’ Their fears were unfounded, as she proved to be very kind. 2

The prejudice of the older hands possibly stemmed from having their male environment disrupted, or from feeling that it was improper for women to live on board. Alternatively, they may have feared that Mrs Lines would cause bad luck. In the western world especially, over the centuries, countless innocent women were accused of being witches, casting spells to cause all manner of harm, including storms and shipwrecks. Women bringing bad luck to ships was therefore a deep-rooted and illogical belief, arising from the need to seek scapegoats or Jonahs to explain and deal with misfortunes.

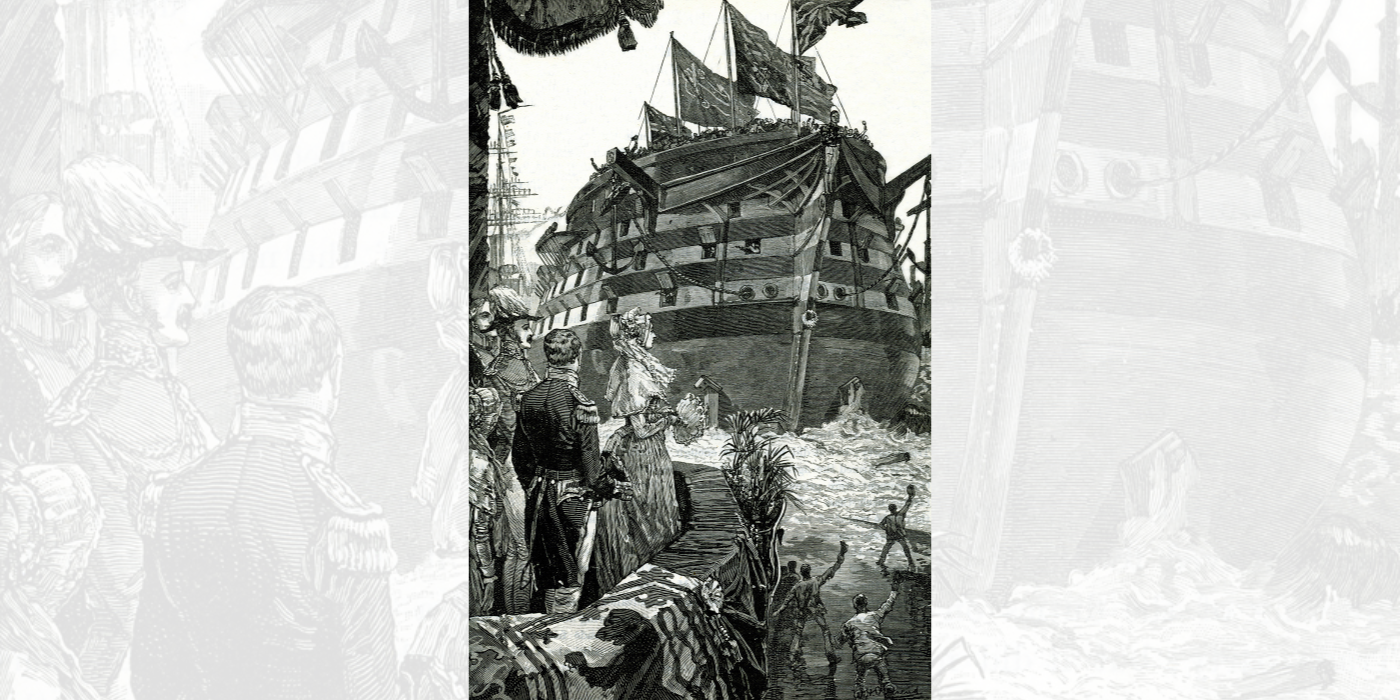

Fishermen were the most superstitious of all seamen, probably because their livelihood depended on good fortune – catching plentiful fish and bringing them home safely. They were always alert for anything that might cause bad luck, as a Liverpool customs officer mentioned in 1944: ‘A fairly general superstition among fishermen was that it was unlucky to meet a woman on the way to one’s boat, especially so if she spoke’. 3 In 1871 the antiquary William Jones noted in his book The Broad, Broad Ocean: ‘The fishermen of the Firth of Forth believe that if they chance to meet a woman bare-footed who has broad feet, when they are going to their vessels, they will have “bad luck”.’ In another book published in 1880, Jones elaborated further: ‘The fishermen of the Firth of Forth believed that if they chanced to meet a woman bare-footed, who had broad feet and flattish great toes, when they were proceeding to go to sea, in their boats, they would have “bad luck,” and, consequently, need not go out in search of fish.’ 4 At Holderness on the east coast of Yorkshire, it was also said that ‘fishermen when going to sea will turn back and wait a tide if they meet a woman wearing a white apron’. 5

1722 map of Holderness

Fishing cobles at Staithes, Yorkshire

1722 map of Holderness

Fishing cobles at Staithes, Yorkshire

The dialect poet Elizabeth Tweddell told Notes and Queries in 1874 that at Staithes on the Yorkshire coast, ‘if a fisherman happens to meet a female first on leaving his cottage to put out to sea, he will turn back again, as he firmly believes that all his luck would be spoiled for the day’. 6 A correspondent of The Times encountered the same superstition when he was at Staithes in 1885, describing the place as so cut off from the modern world that the inhabitants retained many ancient customs, traditions and superstitions. When the women married, he said, they aged prematurely due to their hard labour in preparing the boats for the men to go fishing at night. It was therefore extraordinary that a fisherman might regard his own wife as a harbinger of ill-omen, wielding the evil eye, ‘if as he walks to his boat, his lines on his head or a bundle of nets on his shoulder, he chances to meet face to face with a woman, be she even his own wife or daughter, he considers himself doomed to ill-luck. Thus, when a woman sees a man approaching her under these circumstances she at once turns her back on him.’ 7

Superstition played a key part in shipping before classification societies like Lloyd’s Register and before any adequate insurance for ships and cargoes. Advice and predictions were sought from astrologers such as Simon Forman in London, who compiled details of his consultations on sailors, ships and the sea that took place from 1587 to 1604, including shipowners wanting to know the location and state of their vessels. 8 Another way of improving the chances of a safe voyage was to purchase fair winds from witches living on the coast, something that was often done by seafarers in Scotland, the Isle of Man and Scandinavia. 9 In 1748 one woman on board a ship approaching Virginia was singled out as a witch for having caused severe weather, as the Derby Mercury reported:

Captain Crawford, with Palatines (German emigrants) on board, met with a violent storm off the Capes of Virginia, and was blown from thence to Cape Fare, and back again; and meeting still with bad weather, a mate, and one of the Overseers of the Palatines, took it into their heads, that an elderly woman, who was on board, was a witch, wherefore they threw her over-board; as soon as Capt. Crawford heard of it, he had them both secured, and put into irons, and carried them prisoners to Virginia, where they are to be tried. 10

In 1885 Fletcher Bassett, a retired American naval officer and folklorist, linked women aboard ships with such witches who supposedly drew their power from the Devil or Satan: ‘Women, being regarded as cruel and crafty, were especially his agents, hence were deemed unlucky on board ship, and as witches, possessed of great power over the storm and wave.’ 11 As beliefs in witchcraft diminished, superstitions were less widely embraced, evolving instead into prejudice and discrimination, with a reluctance to accept change. Numerous instances are known of girls and women disguised as seamen on board naval and merchant ships, and whenever one was found out, no subsequent accusations were made about them having endangered the vessels. In the Royal Navy this superstition was rare, and yet it seems to have been why Vice-Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood disliked women on board: ‘I never knew a woman brought to sea in a ship that some mischief did not befall the vessel.’ 12

Through the 19th century, captains of merchant ships increasingly had their wives and families on board, as well as female passengers. 13 In October 1853 George Washington Peck was a passenger on board the American ship Albus that was waiting to load guano at the Chincha Islands, Peru: ‘There are quite a number of ladies—the wives and daughters of captains in the fleet—and we make calls and visits and even have evening parties.’ 14 Not everyone was accepting of women, and the basic superstition of them bringing bad luck persisted. On board the clipper ship the Wild Ranger in 1855, Bethia Sears, wife of Captain Elisha Sears, feared that the sailors would blame their problems on her presence: ‘Elisha says we are having hard luck,’ she wrote, ‘hope it is not because I am here.’ 15

Over four decades later, in response to a shipping disaster, one newspaper commented: ‘We do not say that the presence of the captain’s wife on board caused the unluckiness, but many sailors will point to it as an instance.’16 Around the same time, James Douglas Jerrold Kelley, an American naval officer and storyteller, shared a similar opinion: ‘Lawyers, clergymen, and women are ever looked at with disfavor on sailing ships as sure to bring ill luck ... Women – who may reason out their unpopularity? – save that a ship is the last place for them, or perhaps because of the dread of witches; for of all spell-workers in human form none is so dreaded as the female brewers of hell-broth’. 17

The belief that women caused bad luck on board ship was filled with contradictions, not least because many maritime elements were regarded as female. Ships themselves were thought of and referred to as ‘she’, even when the vessel’s name was masculine (such as HMS Ajax). Many wooden sailing ships had a carved and painted figurehead at the bow, apparently originating in the display of heads of sacrificial victims from earlier times, and as ship designs changed over the centuries, so too did their figureheads. They were revered by the crews and gave the vessels good luck, power and protection. Lions were once especially popular, as were figures that reflected the name of the ship, but by the mid-19th century figureheads tended to be of single figures. Many were females, some of which were bare-breasted, possibly from the ancient belief that naked women could calm storms.18

The figurehead of HMS Ajax

The figurehead of HMS Atalanta

The figurehead of HMS Sybille

The figurehead of HMS Ajax

The figurehead of HMS Atalanta

The figurehead of HMS Sybille

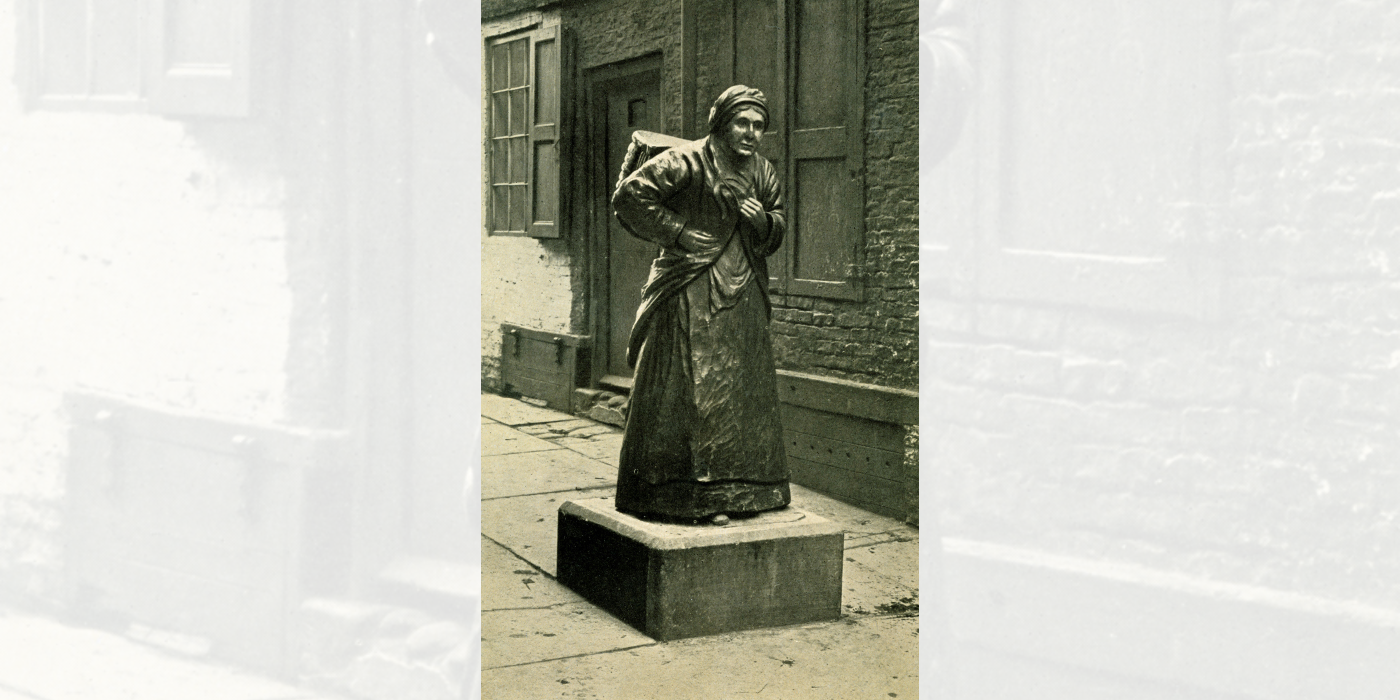

One female figurehead ended up as a global good-luck charm. In 1781 the Alexander and Margaret brig from Tynemouth was badly damaged near Great Yarmouth in an attack by an American privateer. 19 The traditional female figurehead, or ‘dolly’, was removed and set up at Tynemouth, before being shifted in 1814 to nearby North Shields. Sailors began to cut off pieces as protective charms, so that the disfigured dolly had to be replaced several times. In 1890 the local Monthly Chronicle reported that the superstitious ‘sons of Neptune’ engaged in ‘Dolly worship’, which ‘induced them to chip off pieces of the figure to carry over the main with them as a sort of charm against the perils to which their calling exposed them’. 20 Rather than the traditional figurehead, the one carved in 1902 was in the form of a fishwife with shawl and creel, but sailors continued to chip off pieces.

Wooden dolly at North Shields

The River Tyne and North Shields

Wooden dolly at North Shields

The River Tyne and North Shields

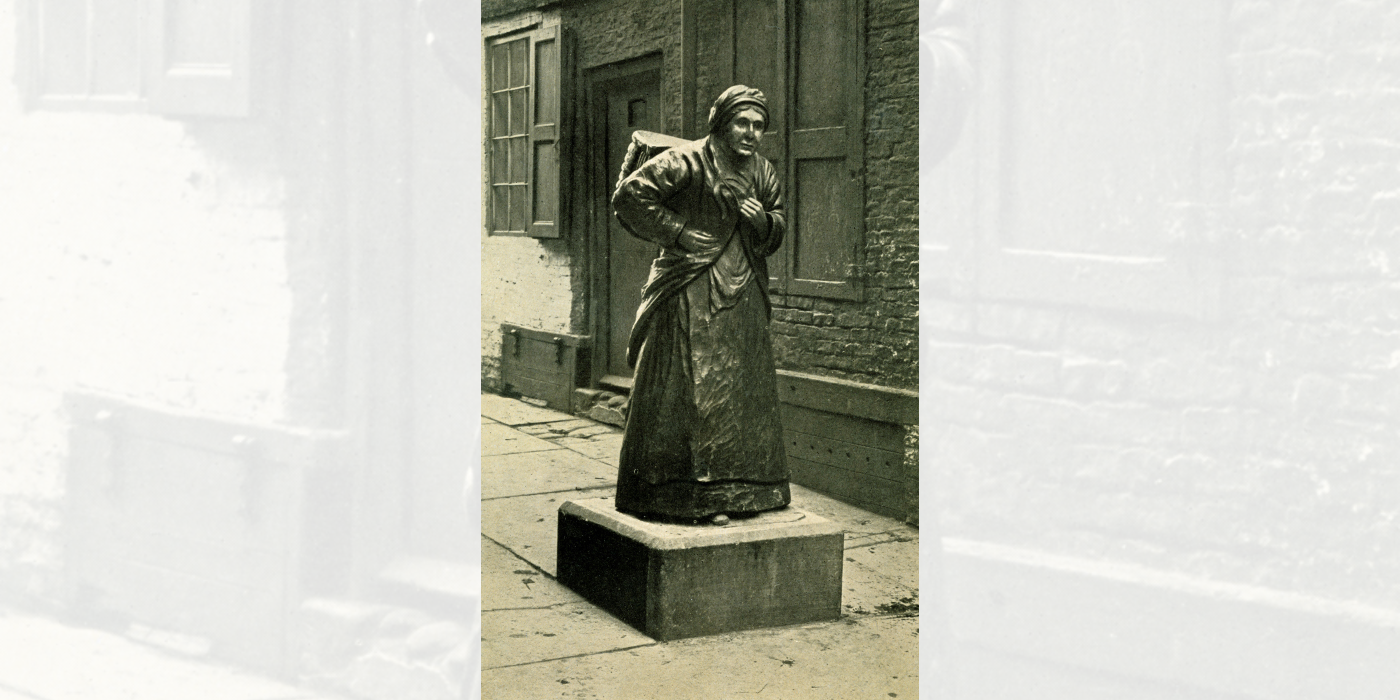

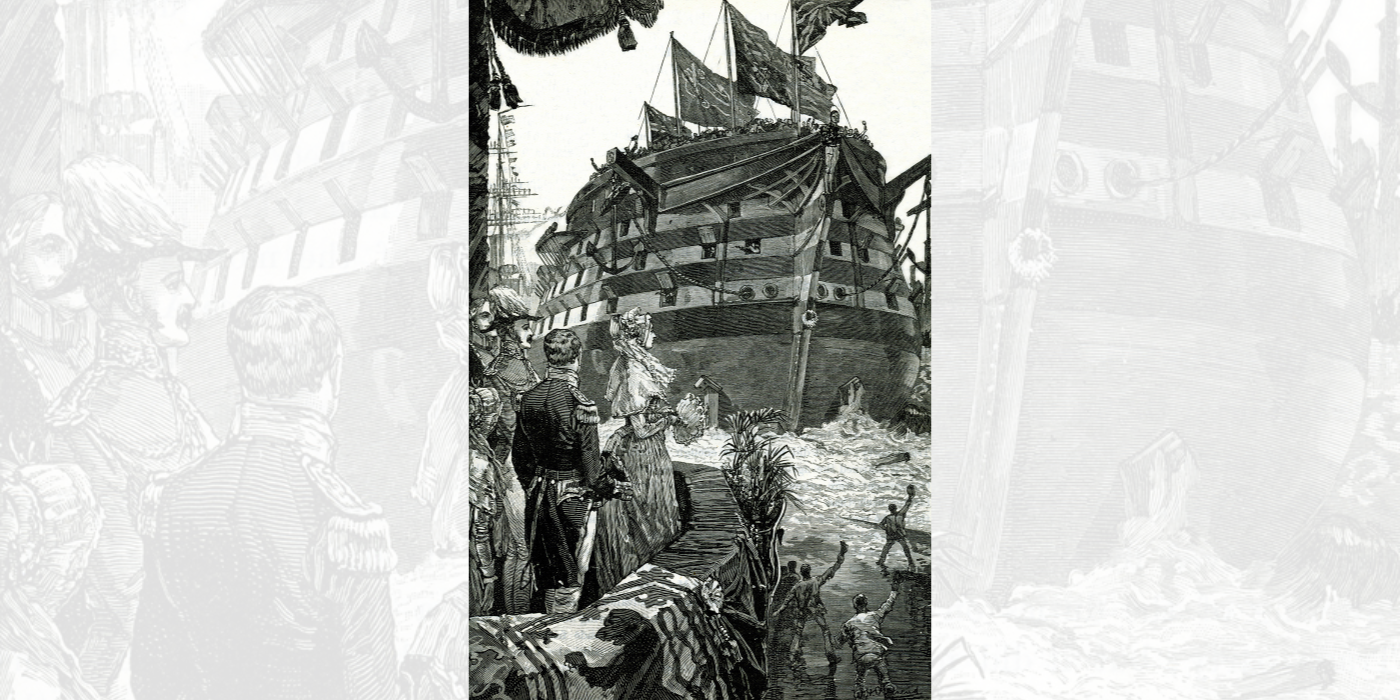

The launching of ships was the occasion when the ship passed from land into water, and it was marked by a blessing and naming ceremony, also referred to as a christening, which had its roots in ancient sacrificial ceremonies. Women did not originally play a part in the official launch, as seamen would supposedly refuse to sail in those vessels – much like the superstition of having women on board. Gradually, though, it became traditional for women, and not men, to launch vessels of all sizes to ensure they had good luck. This was a reversal of beliefs, and yet the involvement of women was seldom mentioned. On 4 July 1795 two vessels were launched at the yard of John and William Wells on the Thames at Rotherhithe, including the Amazon, a 36-gun frigate built for the Royal Navy. One newspaper reported: ‘Lord Spencer and Lord Caernarvon were present. The ceremony of baptizing the frigate was performed by Lady Caernarvon.’21 Other newspapers failed to mention Lady Caernarvon at all.

On the River Thames at Deptford in November 1801, a three-decker East Indiaman, the Baring, was launched at Barnard’s yard, which was notable in being owned and run by a woman, Mrs Frances Barnard. In his newspaper The Porcupine, the radical journalist William Cobbett wrote about the ceremony: ‘At forty minutes after one ... as the ship went gallantly and smoothly from the stocks, the amiable Lady of Captain Medows threw a magnum of claret at the head, exclaiming with a firm and audible voice—success to the BARING.’ The ‘amiable lady’ was Betty Syrett, who Captain Dixon Meadows had married in April, and he would be the Baring’s captain for the East India Company until 1806. Cobbett’s newspaper described the ensuing celebrations, reflecting contemporary attitudes towards women: ‘Barnard’s yard, on this festive occasion, exhibited a splendid appearance of beautiful women, who were afterwards most sumptuously and comfortably entertained.’22

Launch of HMS Trafalgar in 1841

Launch of the E. A. Morse in 1919

Launch of HMS Trafalgar in 1841

Launch of the E. A. Morse in 1919

The Chaa-sze clipper ship was built under special survey at Aberdeen and rated ✠A1 for 13 years by Lloyd’s Register. 23 She was launched on 25 April 1860, as reported by the local newspapers: ‘The whole preparations having been completed, a young lady, a friend of the owners, stepped forward, and gracefully named the vessel “Chaa-sze,” when away she went into her future element in beautiful style.’ 24 The woman’s name was not given, but the captain’s son witnessed that the ceremony went wrong:

Under the figurehead was a railed-in platform, intended for the lady and the party with her who were to perform the ceremony ... The lady who was to christen her, repeating a certain formula (which I have forgotten), revealed to the many listeners the hitherto-concealed name. At the same time she swung the bottle towards the ship with intent to break it and spill the wine over the bow. But alas! unnerved perhaps by the shouting of the carpenters ... the lady lost her head and pulled the cord with insufficient force. The bottle swung back without touching the ship, still intact, its mission unfulfilled. This was a disastrous thing to happen. It was an omen of the very worst kind. 25

Although a carpenter managed to get hold of the bottle and dash it against the ship’s side, it was nevertheless felt that this caused the Chaa-sze to have a series of misfortunes and never be lucky. The fact that blame was not heaped on the young lady perhaps signalled a change in female fortunes.

By the beginning of the 20th century safety at sea had become much more practical and scientific, but superstitions persisted, and when Princess Anne visited a North Sea gas rig in October 1969, the newspapers commented: ‘The Princess was the first official woman to land on the rig. Traditionally, women are not encouraged to visit such installations.’ The Daily Mirror was more explicit: ‘The Princess’s visit – to the Amoco B platform forty miles off the Norfolk coast –– broke a superstition. It made her the first woman to go aboard a North Sea gas rig. Previously, women had not been allowed on because the crews believed they would bring bad luck.’ 26

To discover more stories of trailblazing women in maritime history, explore the Rewriting Women into Maritime History initiative led by the Lloyd’s Register Foundation, Heritage and Education Centre.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Lloyd’s Register Group or Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

Figureheads at the Royal Museums Greenwich

Wooden Dollies of North Shields

Footnotes

-

1

Roy and Lesley Adkins 2008 Jack Tar: Life in Nelson’s Navy (London: Little, Brown), pp 157–8, 173–80, 186–8; David B Clement 2021 Square-Rigger Sunset: The Passages of Four and Five-Masted Ships and Barques volume 2 (Exeter: The South West Maritime History Society), pp 383–4; R Laurel Seaborn 2014 Seafaring Women: An Investigation of Material Culture for Potential Archaeological Diagnostics of Women on Nineteenth-Century Sailing Ships (Master of Arts thesis, East Carolina University), which includes examples of women who were not wives of captains, but fulfilled other roles.

-

2

See p 384 of T C Fairburn 1968 ‘First Voyage in the “Inversnaid”’ Sea Breezes 42, pp 384–9.

-

3

B J Herrington 1944 ‘Sailors are Superstitious’ Transactions of the Liverpool Nautical Research Society 1 no. 15 (no pagination).

-

4

William Jones 1871 The Broad, Broad Ocean and some of its inhabitants (London: Frederick Warne; New York: Scribner, Welford & Co), pp 246–7; 1880 Credulities Past and Present (London: Chatto and Windus), pp 115–16. Jones was a prolific writer and former Vice-Consul at Le Havre.

-

5

See p 355 in William Henry Jones and Lewis L Kropf 1883 ‘Magyar Folk-Lore and Some Parallels’ The Folk-Lore Journal I, pp 354–62. Curiously, similar superstitions about women were present in mining communities.

-

6

Notes and Queries 2, 5th series (1874), p 184. Tweddell was writing here under the name Florence Cleveland.

-

7

The Times 7 September 1885, p 8; The Times 22 September 1885, p 3; Jones 1880, p 134.

-

8

Keith Thomas 1971 Religion and the Decline of Magic: Studies in popular beliefs in sixteenth and seventeenth century England (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson), pp 309–10; E G R Taylor 1933 ‘Sir William Monson consults the stars’ The Mariner’s Mirror 19, pp 22–6; Luís Campos Ribiero 2023 ‘Nautical astrology: a forgotten early modern tradition’ Annals of Science 80, pp 199–231. Forman’s manuscript is held in the Bodleian Library.

-

9

Sir James George Frazer 1911 (3rd edn) The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion Part 1: The Magic Art and the Evolution of Kings (London and Basingstoke: Macmillan Press), pp 325–7.

-

10

Derby Mercury 12 January 1749, p 4.

-

11

Fletcher S Bassett 1885 Legends and Superstitions of the Sea and of Sailors in all lands and at all times (Chicago and New York: Belford, Clarke & Co), p 120.

-

12

Collingwood was writing in 1808 to Rear-Admiral Purvis – see Suzanne J Stark 1996 Female Tars: Women Aboard Ship in the Age of Sail (London: Constable), p 52.

-

13

Seaborn 2014, p 16.

-

14

See p 17 of George W Peck ‘The Chincha Islands’ The Working Farmer 6 no. 1, 1 March 1854, pp. 17–19. See Guano: The Perilous Cargo of Flammable and Noxious Fertiliser.

-

15

Cited in Joan Druett 1998 Hen Frigates: Wives of Merchant Captains Under Sail (London: Souvenir Press), p 150.

-

16

The Shields Daily Gazette and Shipping Telegraph 10 July 1897, p 4.

-

17

See p 422 of J D Jerrold Kelley 1894 ‘Superstitions of the sea’ The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine 48, pp 418–26. Kelley lived 1847–1922.

-

18

The Roman writer Pliny the Elder in his Natural History refers to naked women quelling storms at sea (book 28, chapter 23). See also M K Stammers 1983 Ships’ Figureheads (Princes Risborough: Shire Publications).

-

19

See Lloyd’s Register 1780. Newcastle Chronicle 17 February 1781, p 2, and 24 February 1781, p 2.

-

20

‘The Wooden Dolly, North Shields’ in The Monthly Chronicle of North-Country Lore and Legend 4 (1890), pp 161–2.

-

21

Calcutta Gazette 3 December 1795, p 6 (with a report called LONDON July 7). The Amazon was wrecked in Audierne Bay, France, in January 1797 after sustaining severe damage in battle.

-

22

The Porcupine, and Antigallican Monitor 23 November 1801, p 4.

-

23

Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping from 1st July 1861, to the 30th June, 1862 (London), spelled as ChaaSze. See also Stanley Bruce 2021 Alexander Hall & Co., Shipbuilders, Footdee, Aberdeen: The 1860’s Boom to Bust (Stanley Bruce), pp 36–8.

-

24

The Aberdeen Herald 29 April 1860, p 5.

-

25

Andrew Shewan 1927 The Great Days of Sail: Reminiscences of a Tea-clipper captain (London: Heath Cranton), p 81.

-

26

Liverpool Daily Post 29 October 1969, p 1; Daily Mirror 29 October 1969, p 5.