Death by drowning was a particular fear of mariners, and yet their attitudes to safety at sea were once guided by superstition and custom. Swimming skills in the past and across the world were generally restricted to the poor, though at times became the preserve of the elite. For hundreds of years the most common safeguard against drowning was the possession of an amulet or lucky charm, and a caul was especially prized.

On 27 February 1879 Lieutenant Theodorus B M Mason of the United States Navy read a paper on safety at sea before the American Geographical Society, in which he remarked: ‘The great majority of people cannot swim, and, strange as it may seem to you, there are many who follow the sea as a profession who cannot swim a stroke.’ 1 Throughout history, attitudes towards swimming fluctuated and tended to be influenced by religion and superstition, alongside a fear that sea monsters, mermaids, demons and spirits of the deep were waiting to drown victims. Swimming was commonly viewed as dangerous and indecent, connected particularly with the lower classes, barbarians and slaves, though it also developed into a heroic, elite activity. 2

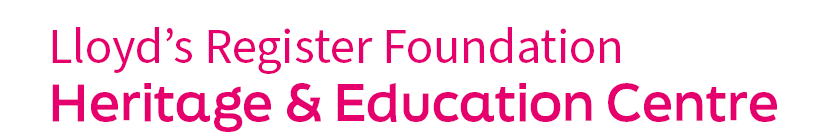

Swimming manuals appeared in western Europe from the 16th century, when the benefits of swimming came to be recognised and were linked to the exploits of ancient Greece and Rome. At the same time, swimming was perversely banned in some places, such as for university students in Cambridge, while from the late 16th century women in Britain and much of northern Europe faced being put on trial by water (known as ‘witch swimming’) for alleged crimes. Being able to swim was risky, since their trial involved being cast into rivers or ponds with their hands and feet bound. Because witches and heretics had supposedly renounced baptism, any water rejected them, and they therefore floated, unable to drown, which was proof of their guilt. Those who sank were innocent. 3

By the 19th century, learning to swim was encouraged, but most working people had scant opportunity and were in any case prey to superstition and custom, with mariners being especially susceptible. They invariably had an illogical view of what was best for their safety, including the prevention of drowning and saving others. The Reverend Walter Gregor was a Scottish folklorist who encountered one superstition that those destined to die by drowning had a depression called ‘the water glance’ on their brow at birth, often visible only to midwives. Death by drowning occurred when the depression disappeared. There was also a shocking reluctance to rescue anyone who was drowning, which Gregor came across in Shetland and some parts of the Scottish mainland: ‘It arises from the notion that the one who saves another from drowning will in no long time be drowned. The sea takes the saver of life instead of the saved, as it “maun hae its nummer,” according to the saying.’ 4

Drowning at sea

Witch swimming

Drowning at sea

Witch swimming

At about one in the morning of 30 May 1909, close to Stornoway Harbour in the Outer Hebrides, six men lost their lives when their rowing boat was swamped and sank. One newspaper expressed disbelief that mariners like these chose not to learn to swim:

The inability of many fishermen and seamen to swim is deplorable, and what is more pitiful is that in very many cases this inability is wilfully due to a superstition that to learn to swim is to court a watery grave. A crusade is needed to dispel this superstition, and encourage the art of natation (swimming) among the seafaring population. 5

Over two decades later, on 11 May 1930, George Richard Empson Green, a 55-year-old deck hand, was washed overboard from the trawler Ocean Lover, between Beachy Head and Dungeness, when a huge wave struck. His body was not found. Three days later, when back at their home port of Great Yarmouth, an inquiry was conducted by George E Morgan, the local Superintendent of Mercantile Marine. When asked if the deceased man could swim, Skipper Cobb remarked: ‘The number of fishermen who can swim is very small’. George Green’s younger brother, William James Empson Green, owned the trawler, and he agreed, saying that ‘not five per cent of Yarmouth fishermen could swim across the harbour’. Mr Morgan suggested that it would surely be advantageous if they learned to swim, but William Green said: ‘They think they can never swim ashore, so they never try to learn.’ Mr Morgan then commented that he had heard fishermen refusing to learn to swim because it prolonged the agony of drowning. 6

Swimming at Great Yarmouth

Drowning at Sapperton

Swimming at Great Yarmouth

Drowning at Sapperton

The most popular way that seafarers and travellers protected themselves from drowning was the possession of a caul, an amulet that had been depended on in many countries since antiquity. A caul is part of the thin amniotic membrane that occasionally remains intact over a baby’s head at birth and was frequently referred to as a ‘silly-how’ in northern England and Scotland and by countless other names in different countries. As long as the caul was not lost, discarded or destroyed, it supposedly brought a child good luck, warding off ill-health, evil spirits and disaster, especially drowning. The protection transferred to any purchaser of a caul, and for sailors that also meant the vessel he was sailing in. 7

In 1742 William Smellie was working as a man-midwife in London and wrote about one poor woman who gave birth and preserved the caul: ‘She expressed great joy when she knew the child was born with a cawl, which she dried and carefully kept, in full persuasion, that her child would never suffer extremity either by sea or land, while it remained in her possession.’ He later said: ‘I never tell the good women whether or not the membrane remains upon the child’s head, that they may not have an opportunity of indulging an idle superstition.’8

Cauls would have been worn or kept safe in different ways. In ‘The Sea-Spell’, a 21-verse poem published in 1826, the poet and humorist Thomas Hood portrayed a mariner who was oblivious to the dangers of an approaching storm because he had a caul:

For, in his pouch, confidingly,

He wore a baby’s caul. 9

Hood’s mariner kept his caul in a pocket or purse that was probably worn round his waist. George Miller was a 40-year-old seaman whose boat capsized in the River Thames near St Katharine’s Docks in November 1863. Although the other men in the boat were rescued, Miller died by drowning. An inquest was held at the Green Man Tavern in Poplar, and the Evening Standard newspaper reported: ‘It appeared that the deceased wore around his neck as a charm a bag containing a child’s caul and a lock of his wife’s hair and said that he would never be drowned while he had them on.’ 10

Entrance to the London Docks

A preserved caul

Entrance to the London Docks

A preserved caul

Walter Gregor observed that even owning a sliver of a caul sewn into clothing was valued:

Many an emigrant has gone to the possessor of such a powerful charm, got a nail’s breadth of it, sewed it with all care into what was looked upon as a safe part of the clothes, and worn it during the voyage, in the full belief that the ship was safe from wreck, and would have a prosperous voyage. 11

During the Second World War, on 9 April 1940, the destroyer HMS Gurkha was sunk off Norway. Seaman George Dinning, who was 18 years old, came from the colliery village of New Seaham and survived the disaster. He explained to the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle newspaper what happened: ‘I kept the caul in my bunk, and when I realised that the ship was sinking, I hurried below and secured it, and shortly afterwards I was ordered into a lifeboat. I still have the caul.’ The newspaper emphasised the reason he gave for his survival: ‘He believes that his good luck is due to a caul with which he was born ... There is an old superstition among seamen that anyone possessing a caul will never be drowned.’ 12

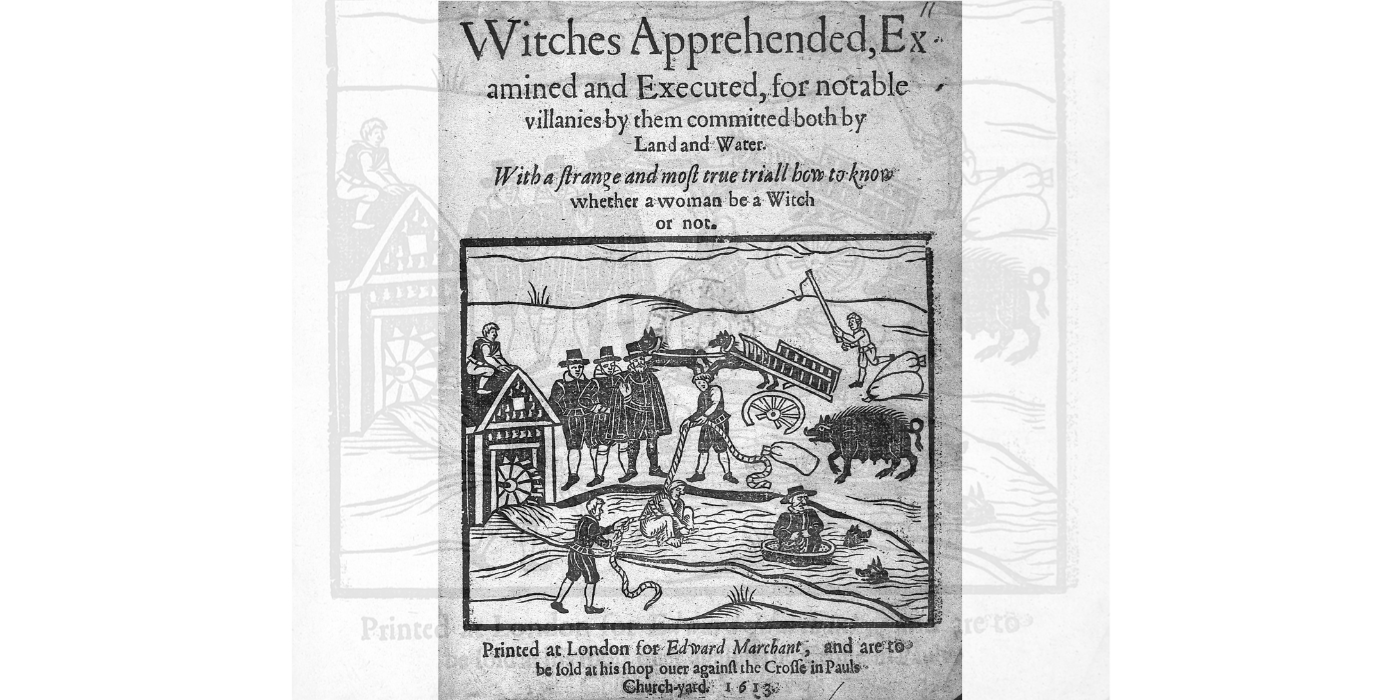

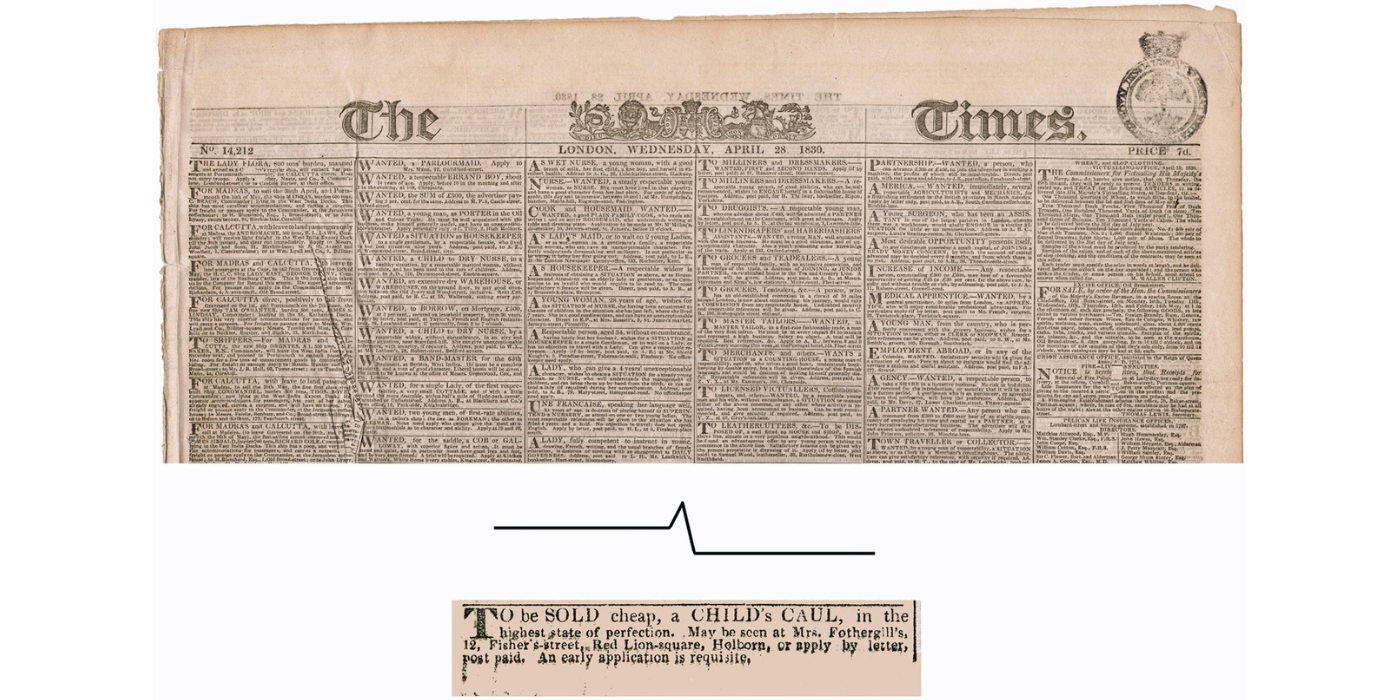

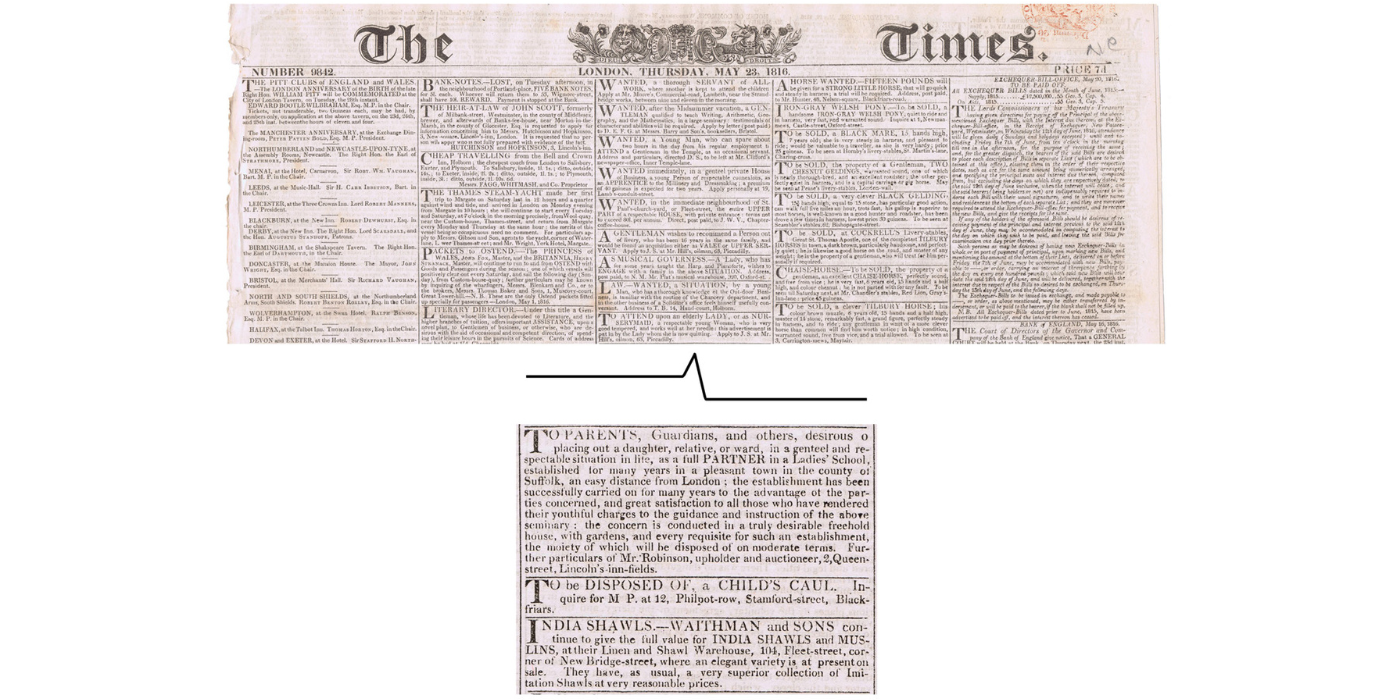

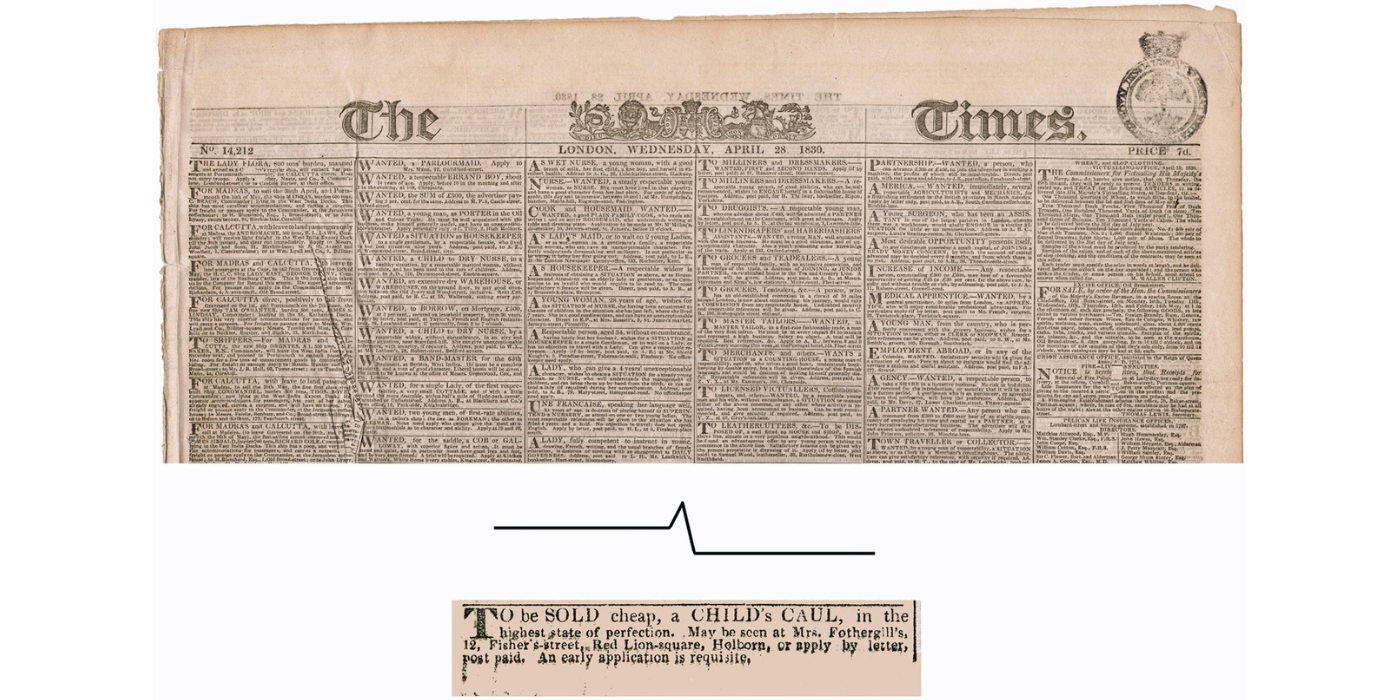

Newspapers often printed advertisements for cauls, including one at Poplar in the Morning Advertiser for 31 March 1837: ‘PRESERVATION at SEA.––To be SOLD a CAUL, on moderate terms. Apply at Mr. Best’s, No. 13, North-street, Poplar.’ The front page of The Times for 8 May 1848 had no less than three London advertisements for cauls, one of which had apparently kept its late owner safe for decades:

A CHILD’S CAUL. Price six guineas. Apply at the bar of the Tower Shades, corner of Tower-street. The above article, for which £15 was originally paid, was afloat with its late owner 30 years in all the perils of a seaman’s life, and the owner died at last at the place of his birth.13

One of the most famous novels is David Copperfield by Charles Dickens, published in serial form from 1849 to 1850. The opening chapter has David Copperfield describe how his own caul failed to sell:

I was born with a caul, which was advertised for sale, in the newspapers, at the low price of fifteen guineas. Whether sea-going people were short of money about that time, or were short of faith and preferred cork-jackets, I don’t know; all I know is, that there was one solitary bidding.

Dickens had fun describing how David Copperfield’s unwanted caul was eventually sold in a raffle:

The caul was won, I recollect, by an old lady with a hand-basket ... It is a fact which will be long remembered as remarkable down there, that she was never drowned, but died triumphantly in bed, at ninety-two. I have understood that it was, to the last, her proudest boast, that she never had been on the water in her life, except upon a bridge.

An advertisement for a caul in The Times in 1816

An advertisement for a caul in The Times in 1830

An advertisement for a caul in The Times in 1816

An advertisement for a caul in The Times in 1830

Interest in cauls certainly waned, and in January 1899 The Lancet commented on a medical man being asked if he wanted to purchase a caul or was able to suggest where one could be sold:

We believe there is still some market for cauls among sailors who retain their belief in the efficacy of the membrane as a protection against shipwreck and drowning ... Notices of ‘Cauls for Sale Within’ were to be seen recently in the vicinity of the docks both of London and Liverpool, but it is some time since we have noticed an advertisement of a caul for sale in the daily press. 14

Cauls actually continued being advertised in newspapers into the 20th century, and the baby’s sex was increasingly given, as at Portsmouth in 1902: ‘CHILD’s Caul for Sale, female. –– Apply 114, Clive-road, Fratton’. In 1910 Edward Lovett, a member of the Folklore Society, mentioned that prices had fallen greatly: ‘now they have scarcely any value except for a museum’. Five years later, during the First World War, he was in east London and discovered that they were again in demand:

To-day ... I happened to be in the neighbourhood of the Docks, and saw this notice in a shop window:––

TO SAILORS:

A CHILD’S CAUL

FOR SALE.

As this is a subject in which I am much interested, I went in and asked if there was any demand for such things now, seeing that this old superstition was supposed to have died out. To my surprise the answer was that a strong demand had sprung up, after being dormant for so many years, owing to the great danger of submarines.15

He was sure that the demand had originally subsided because ships seemed much safer, so he was fascinated by this resurgence: ‘The present War has created a terrible danger to life on the sea, by means of the submarine, and consequently the revival of a latent superstition.’

Cauls were prized beyond the First World War, though fewer advertisements appeared, with a typically brief one in a Liverpool newspaper in 1930: ‘STORMS––Safety at Sea.––CAUL for Sale.––Box D 35, The Journal of Commerce, Liverpool.’ Cauls were even offered during the Second World War, as in the Portsmouth Evening News in May 1941:

CHILD’S Caul for sale. What offers?––Write Box 107, News office

WHAT OFFERS?––Baby’s Caul three days’ old boy––Apply 12, Montgomerie Rd, Southsea. 16

Until recent decades, superstitions played a significant part in many people’s lives, though there were dissenting voices. Not everyone valued the efficacy of cauls, and as far back as 1795 the man-midwife Thomas Denman suggested that the purpose of the superstition was to stop midwives doing harm: ‘To this cawl imaginary virtues have been attributed, and a fancied value has been set upon it. It was esteemed the perquisite of the midwife, and perhaps the whole was the contrivance of some intelligent man, to prevent her from interfering with any labour, which was going on in a natural way.’ 17

In his poem ‘The Sea-Spell’, Thomas Hood satirised the belief in cauls and caused his reckless mariner to drown:

The jolly boatman’s drowning scream

Was smother’d by the squall.

Heaven never heard his cry, nor did

The ocean heed his caul! 18

After the inquest in December 1863 into the drowning in the Thames of George Miller, who had worn a caul, the Evening Standard newspaper was exasperated:

We have little hope that men who are silly enough to carry about a child’s caul to prevent drowning will learn wisdom from the proved futility of this ridiculous safeguard, but to the general reader the case is instructive, as showing incidentally the extent of superstition in this boasted age of enlightenment. 19

While cauls were undeniably the foremost method of preventing drowning, mariners also put their trust in other lucky charms and beliefs, such as the wearing of gold earrings and particular tattoos. Edward Lovett in 1910 said that he had met sailors who carried small model anchors as a charm against drowning. He added: ‘Another charm against drowning, carried by the sailors of South Devon, is the “Merry-Thought” bone (wishbone) of a fowl, whereas in Yorkshire I found the small T shaped bone from a sheep’s head carried for the same reason.’ 20

An annual custom of ‘hunting the wren’ on Christmas Day, Boxing Day or New Year’s Day once took place across England, Wales, Ireland and the Isle of Man, as well as France and America. 21 On the Isle of Man the cruelty was justified as providing Manx fishermen with feathers to protect them from shipwreck. In 1816 Hannah Ann Bullock wrote about this superstition’s history:

They are pursued, pelted, fired at ... and their feathers preserved with religious care, it being an article of belief, that every one of the relics gathered in this laudable pursuit, is an effectual preservative from shipwreck for one year; and that fishermen would be considered as extremely foolhardy, who should enter upon his occupation without such a safeguard.

In 1869 another Manx historian, William Harrison, said that this custom was carried out mainly by boys. After catching a wren, they suspended it in garlands and evergreens and went on a procession, calling at each house, where they gave a feather for luck:

These are considered an effectual preservative from shipwreck, and some fishermen will not yet venture out to sea without having first provided themselves with a few of these feathers to insure their safe return. The ‘dreain,’ or wren’s feathers, are considered an effectual preservative against witchcraft. 22

A Great Britain farthing with a wren

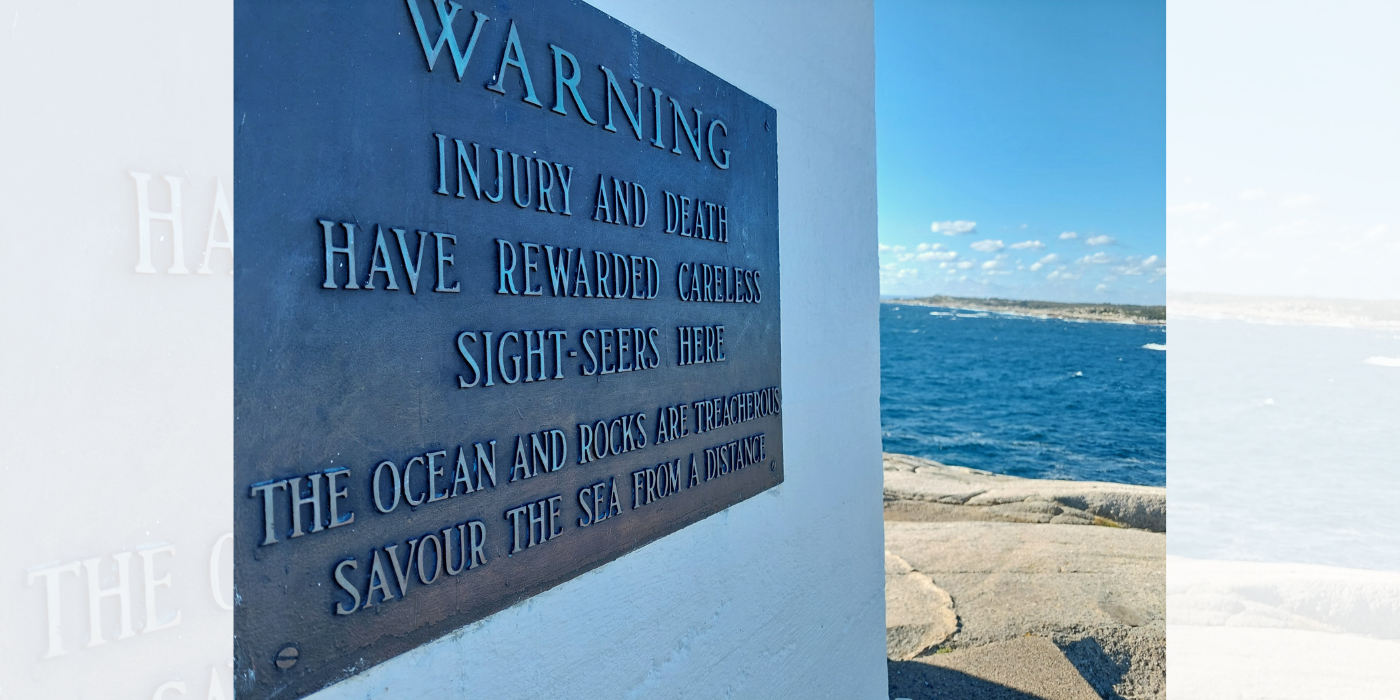

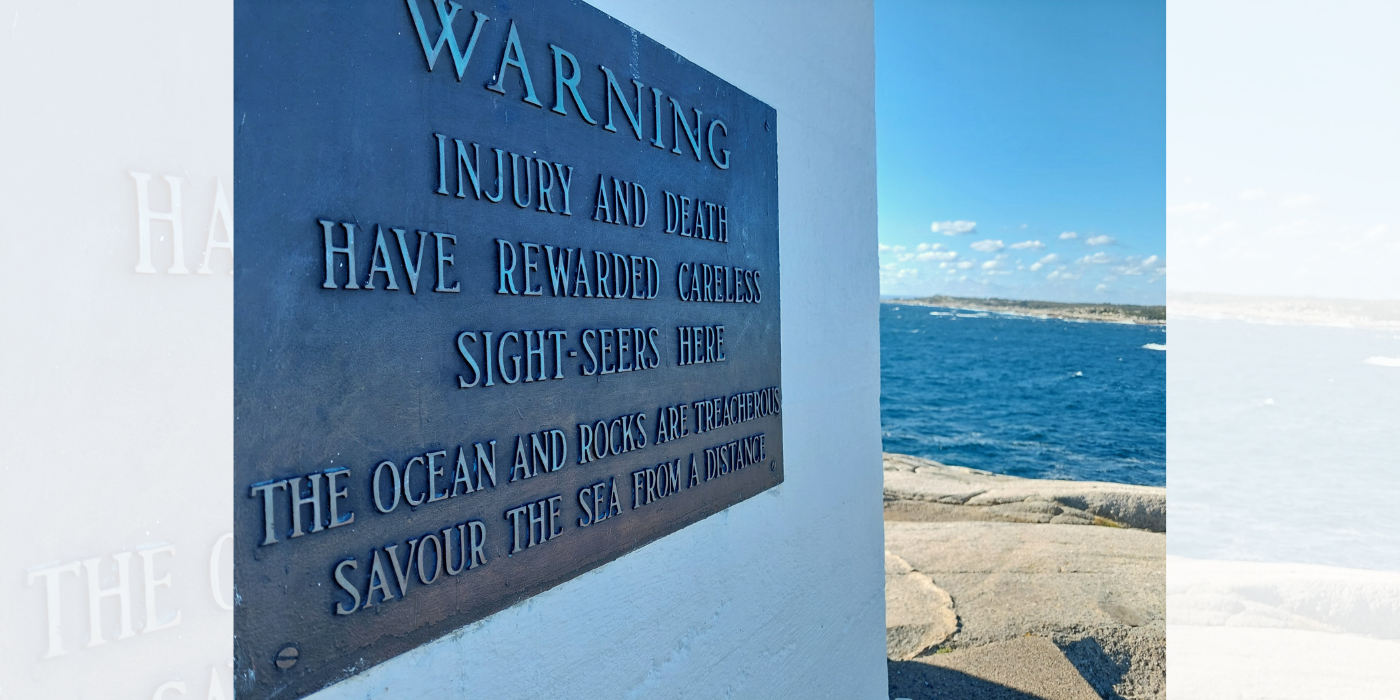

Danger at Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia

WARNING

INJURY AND DEATH

HAVE REWARDED CARELESS

SIGHT-SEERS HERE

THE OCEAN AND ROCKS ARE

TREACHEROUS

SAVOUR THE SEA FROM A DISTANCE

A Great Britain farthing with a wren

Danger at Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia

WARNING

INJURY AND DEATH

HAVE REWARDED CARELESS

SIGHT-SEERS HERE

THE OCEAN AND ROCKS ARE

TREACHEROUS

SAVOUR THE SEA FROM A DISTANCE

Witches were not only tried by water, but were often blamed for raising storms, so these wren feathers were a powerful preservative against witches, storms, shipwrecks and drowning, at a time when people would cling to superstitions to help them survive in a turbulent world. Past customs can be almost beyond our comprehension. Even today, drowning is a significant risk worldwide, and the World Health Organization has designated 25 July as ‘World Drowning Prevention Day’.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Lloyd’s Register Group or Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

Footnotes

-

1

Theodorus B M Mason 1879 The Preservation of Life at Sea (New York: American Geographical Society), p. 3.

-

2

Karen Eva Carr 2022 Shifting Currents: A World History of Swimming (London: Reaktion Books).

-

3

Carr 2022, pp. 236–50, 266, 270–3; Eric Chaline 2017 Strokes of Genius: A History of Swimming (London: Reaktion Books), pp. 101–12. Trial by water was an early medieval practice that was resurrected in the late 16th century.

-

4

See p. 184 of Walter Gregor 1885 ‘Some Folk-Lore of the Sea’ The Folk-Lore Journal 3, pp. 180–4. The dialect phrase means that the sea ‘must have its number’. See also Fletcher S Bassett 1885 Legends and Superstitions of the Sea and of Sailors in all Lands and at all Times (Chicago and New York: Belford, Clarke & Co), pp. 466–9.

-

5

The Belfast News-Letter 5 June 1909, p. 10. The overloaded boat was transporting ten men, mainly from Grimsby and Aberdeen, to different fishing vessels and other craft. Some men were wearing heavy boots, so may not have survived even if they could swim (The Greenock Telegraph and Clyde Shipping Gazette 31 May 1909, p. 1).

-

6

The Midland Counties Tribune 16 May 1930, p. 3; Evening Herald (Dublin) 13 May 1930, p. 1; Lancashire Evening Post 14 May 1930, p. 8. The Green brothers were from Winterton-on-Sea in Norfolk.

-

7

See p. 412 in Christina Hole 1957 ‘Some Folklore Survivals in English Domestic Life’ Folklore 68, pp. 411–19; and p. 186 in Christina Hole 1967 ‘Superstitions and Beliefs of the Sea’ Folklore 78, pp. 184–9. Many attributes of cauls (not just protection from drowning) are discussed in Thomas R Forbes 1953 ‘The Social History of the Caul’ Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 25, pp. 495–508.

-

8

William Smellie 1754 A Collection of Cases and Observations in Midwifery (London: D Wilson and T Durham), pp. 235, 238–9.

-

9

Thomas Hood 1826 Whims and Oddities, In Prose and Verse (London: Lupton Relfe), pp. 133–8; 1854 new edn Whims and Oddities, In Prose and Verse (London: Edward Moxon), p. 142.

-

10

Evening Standard 2 December 1863, p. 4.

-

11

Walter Gregor 1881 Notes on the Folk-Lore of the North-East of Scotland (London: Folk-Lore Society), p. 25.

-

12

The Newcastle Weekly Chronicle 20 April 1940, p. 6.

-

13

Morning Advertiser 31 March 1837, p. 1; The Times 8 May 1848, p. 1.

-

14

The Lancet 14 January 1899, p. 137.

-

15

Portsmouth Evening News 19 December 1902, p. 5; Croydon Guardian and Surrey County Gazette 17 December 1910, p. 9; East London Observer 11 September 1915, p. 3.

-

16

Liverpool Journal of Commerce 7 January 1930, p. 5; Portsmouth Evening News 16 May 1941, p. 5.

-

17

Thomas Denman 1795 An Introduction to the Practice of Midwifery vol. 2 (London: J Johnson), p. 37 fn.

-

18

Hood 1826, pp. 133–8; 1854, p. 142.

-

19

Evening Standard 2 December 1863, p. 4.

-

20

Lindsey Shaw 2007 ‘Tattooing’ in John B. Hattendorf (ed.) The Oxford Encyclopedia of Maritime History volume 4 (Oxford University Press), pp. 93–6; Croydon Guardian and Surrey County Gazette 17 December 1910, p.9.

-

21

Roy and Lesley Adkins 2021 When There Were Birds: The Forgotten History of Our Connections (London: Little, Brown), pp. 303–6.

-

22

Hannah Ann Bullock 1816 History of the Isle of Man, with a comparative view of the past and present state of society and manners (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown), p. 371; see pp. 151–2 in William Harrison 1869 ‘Customs and Superstitions’ Mona Miscellany 16, pp. 135–75.