Anybody who lives around or has visited the coast of the United Kingdom has at one point seen the bright orange lifeboats of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution, better known as the RNLI. Meanwhile, those inland may have seen their collection boxes dotted around shops and pubs throughout the country. The RNLI is a vital part of Britain’s maritime safety network, aiding people in distress on the water at any time of day, any day of the year, all in the name of their core mission: saving lives at sea. This year, 2024, marks their 200th anniversary. Such a long history one would imagine is a storied one. Indeed, it is impossible to cover in one short article. Each of their 238 1 lifeboat stations around the coastline has books dedicated to its individual history and notable rescues it participated in. It is too much to cover. Instead, this shall be an overview of the general history of the Institution, and how it rose from one man’s vision to a ubiquitous staple of coastal life.

The inciting incident for the RNLI’s founding was the tragedy of Racehorse, a naval ship disaster which killed six sailors and three men who were helping rescue them. It was one of many shipwrecks witnessed around Douglas on the Isle of Man by Sir William Hillary. He had had enough. Something needed to be done. He reached out to his connections in government, but the Admiralty refused to help 2. Instead, Sir Hillary appealed to society’s philanthropists. In March 1824, in the London Tavern at Bishopsgate, the National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck had its first meeting. It boasted many notable patrons, including the Archbishop of Canterbury as chair, and King George IV as patron 3. At first, with such esteemed backers, it was a success. Instead of training volunteers as it does today, the Institution provided lifeboats and encouraged ordinary people to rescue shipwreck survivors through medals and cash rewards. The medals are a tradition which persists to this day. However, money began running dry by 1849 due to a lack of leadership and sustained fundraising. Annual income was only £354 4.

A 2020 RNLI medal for long service, featuring a profile of Sir William Hillary. Licensed under Creative Commons.

But fortunes soon turned. In 1850, new secretary Richard Lewis and the board under him renewed interest among social elites, most notably convincing Victoria and Albert to become patron and subscriber, respectively. By 1900, annual income was up to £100,000. 5 A large boost came in 1891 thanks to business magnate Charles Macara. He watched the disastrous rescue of Mexico in 1886, which cost the lives of many RNLI volunteers. He and his wife dedicated the rest of their lives to fundraise, publicise, and promote the organisation. This culminated in “Lifeboat Day” five years later, first held in Manchester: a parade of lifeboats designed to raise funds from ordinary people in cities. A roaring success, raising £6000, it was soon followed by similar days in other British cities. The tradition continues to this day.

A 1928 poster encouraging RNLI donations from "Pictorial and Descriptive Guide to Penzance and West Cornwall (11th ed.)"

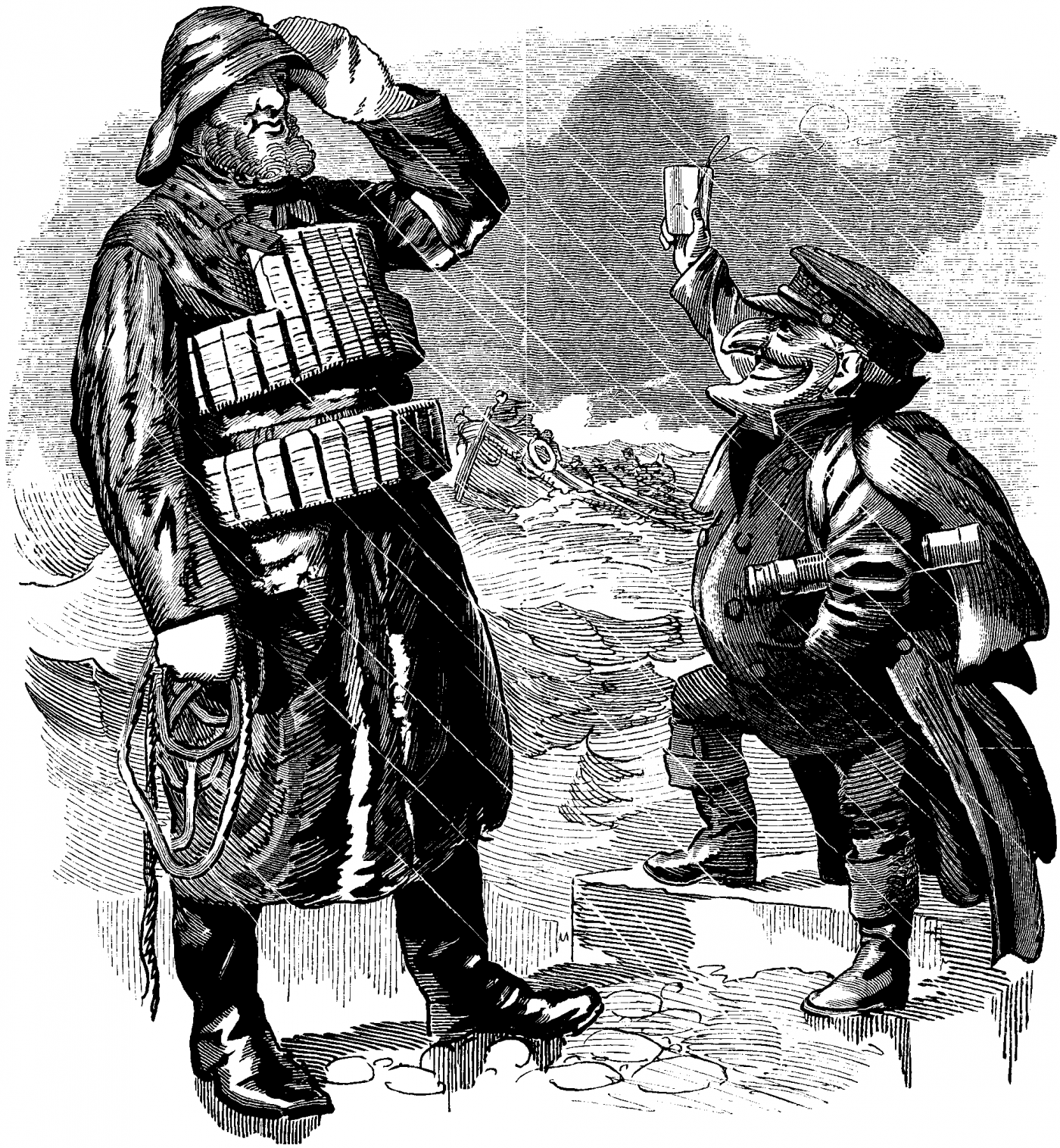

As well as changes to funding, the Institution began to develop its lifeboats and their volunteer crews. Life jackets made of cork were introduced in 1854, as well as oilskin uniform. This was also when the Institution got a new name: Royal National Lifeboat Institution, or RNLI.

A 1892 illustration from Punch magazine showing the oilskin uniform and cork lifejacket that was the uniform of volunteers at the time. From Project Gutenberg.

As well as crew equipment, lifeboats were redesigned to newer, better models: the Peake, the Richardson, the Norfolk, the Suffolk, and the Watson types. Innovation continued, and 1890 brought with it the first mechanised lifeboat, the hydraulic steam powered Duke of Northumberland 6. Steam power was used for a while, but petrol was the way forward. The first such lifeboat, J.McConnel Hussey launched in 1905 7.

This success was interrupted by the World Wars. Young men left to fight in the World War One, leaving only older men to man the boats. Despite this and other challenges of the war, such as mines hindering operation, RNLI continued its lifesaving work. Income grew modestly, as the war limited money and fundraising activity until 1918. After the war, this restored flow of money went into building bigger, better, motorised lifeboats, retiring the old sail and row boats. During World War Two, 18 stations ranging from Lowestoft to Poole helped the Dunkirk evacuation 8. Despite facing similar challenges to those seen in World War One, they continued to save lives, work that was as vital as ever in the face of the U-boat threat. They rescued airmen that has crashed in the Channel, whether allied or Axis. The RNLI did not discriminate; it only focused on saving lives.

After the war came the most rapid period of change. Diesel became the boat fuel of choice. From 1951 to 1961, the number of diesel-powered boats went from 11 to 122 9, many of them older boats that had been fitted with an engine. Self-righting boats also became standard around the 1970s, making things safer and smoother for their crews. Women began to join said crews from the late 1960s onwards 10, forming a needed infusion to the talent pool. The type of rescue shifted from shipwrecks to ordinary people who found themselves in distress at sea, prompting a new type of small, fast, lifeboat, an inflatable known as the D-class, introduced in 1963. New ways of fundraising and gaining attention for the charity also surfaced, most notably through the television show “Blue Peter” in 1966 through a book collection appeal 11. They have done this many times since then, with all boats being named after them.

The first "Blue Peter", a class D inshore rescue boat, purchased through donations from the TV show of the same name. From the Science Museum group collections.

Licensed under Creative Commons.

The RNLI also began collaborating with the coastguard to do combined operations with their lifeboats and helicopters. Though the crews remain volunteers, few of them come from maritime backgrounds, instead being ordinary people trained by the charity in rescue, as long as they are fit and cooperative. Lloyd’s Register Foundation has supported the training of RNLI crew for many years through funding a Crew Emergency Procedures (CEP) course at the RNLI's Sea Survival Centre.

Jayne George from the RNLI said: "Most of our volunteer crew members do not come from a maritime background, making training fundamental. The sea is very unpredictable and, even with the best training, things can occasionally go wrong. The CEP course delivers high quality training to equip crew members with safety skills for their own survival should the worst happen, so that they can save lives at sea safely and effectively."

As the 21st century came upon us, the RNLI modernised still. To help with the growing number of sea rescues of ordinary people from beaches. Professional RNLI lifeguards began work in 2001.

RNLI lifeguard station in Portstewart, 2011. Seen here are the flags which indicate where it is safe to swim. Licensed under Creative Commons, copyright Rossographer.

The same year, the RNLI began to operate inshore services on Lough Erne in Northern Ireland, which have expanded now to cover the London Thames and Loch Ness. As well as rescue, prevention is now focus, with education of sea safety being a vital part of the service.

These days, the RNLI continue to do what they have always done: prevent loss of life at sea, without discrimination. Whether it be sailors, animals, pleasure-seekers, beach-goers, or lately, migrants 12, the RNLI’s volunteer crews will continue their lifesaving work. With an annual income of £205.5 million as of 2022 13, much of that from public donation, it seems they will keep saving lives for a long time, just as Sir William Hillary wished in 1824.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Lloyd’s Register Group or Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

'Searchlight': An RNLI and Lloyd's Register Foundation film

You can find out more about the women in the RNLI in our film, Searchlight, a documentary that highlights the critical role of young women in saving lives at sea.

Women of the RNLI can be visited in person from 2 March – 1 December 2024. This exhibition at the National Maritime Museum (NMM) in Greenwich, London, celebrates the work of women in the Royal National Lifeboat Institution. Featuring striking photography, personal testimony and breathtaking film, the exhibition offers a window into the lives of volunteers across the UK and Ireland. It was curated by the Lloyd’s Register Foundation Senior and Public Curators of Contemporary Maritime who also compiled new oral history recordings and acquired a new photograph collection of lifeboat stations and crew, captured by Jack Lowe.

LRF support for the RNLI

Lloyd's Register Foundation Impact Story - Helping the RNLI save lives at sea

Lloyd's Register Foundation News Article - £1M support helps fund local UK lifesavers

Footnotes

-

1

“RNLI Lifeboat Stations - Stations in the UK and Ireland.” RNLI Lifeboats, rnli.org/what-we-do/lifeboats-and-stations/our-lifeboat-stations. Accessed 20 May 2024.

-

2

“How the RNLI Was Founded in 1824 - One Man’s Vision.” RNLI Lifeboats, https://rnli.org/about-us/our-history/timeline/1824-our-foundation. Accessed 20 May 2024.

-

3

Beardsley, Martyn R., Heroes of the RNLI: The Storm Warriors (United Kingdom,Pen & Sword Books, 2021) p.6

-

4

Cameron, Ian, Riders of the Storm (Orion, London, 2009) p.129

-

5

“Income and Expenditure.—1st Jan. To 31st Dec. 1900”, Lifeboat magazine, vol. 18, May 1901, pp.10-41

-

6

“Lifeboats.” The Pictorial History Of Harwich, Dovercourt & Parkeston., harwichanddovercourt.com/lifeboats.html. Accessed 20 May 2024.

-

7

“1905: First Motor Lifeboat - Timeline - Our History - RNLI.” RNLI Lifeboats, rnli.org/about-us/our-history/timeline/1905-first-motor-lifeboat. Accessed 20 May 2024.

-

8

“Evacuation of men of the British expeditionary force and the french army from dunkirk.* The work of the life-boats of Ramsgate and Margate.”, Lifeboat magazine, vol. War Years, pp. 69-79

-

9

Cameron, Riders of the Storm p.129

-

10

To Save Every One: 200 years of RNLI courage: the official and definitive illustrated history of the RNLI HarperCollins, London, 2024) p.50

-

11

“Blue Peter Inshore Rescue Life-Boat: Science Museum Group Collection.” Blue Peter Inshore Rescue Life-Boat, Science Museum Group, collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co42059/blue-peter-inshore-rescue-life-boat-blue-peter-1-class-d-lifeboat. Accessed 20 May 2024.

-

12

“RNLI Releases New Figures to Highlight Crews’ Lifesaving ...” RNLI Lifeboats, rnli.org/news-and-media/2023/june/14/rnli-releases-new-figures-to-highlight-crews-lifesaving-impact-in-the-channel. Accessed 20 May 2024.

-

13

RNLI annual report and accounts, RNLI, 2022, p.48